To save the planet, ask the locals

Simply sign up to the Sustainability myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Scientists and policymakers can — and have — come up with creative, inspiring and practical ways to tackle the world’s environmental challenges, but attempts to implement them without involving local and indigenous people are likely to fail.

Indigenous people make up 6 per cent of the global population but manage or have tenure rights over more than a quarter of the world’s land surface. “There is simply no way to halt climate breakdown if indigenous peoples aren’t included,” says Conservation International (CI), a US-based non-profit organisation.

A 2020 study, published in the Ecological Society of America’s journal ‘Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment’, found that 36 per cent of the world’s intact forest landscapes (forests undisturbed by human activity) lie within indigenous lands “making these areas crucial to the mitigation action needed to avoid catastrophic climate change”.

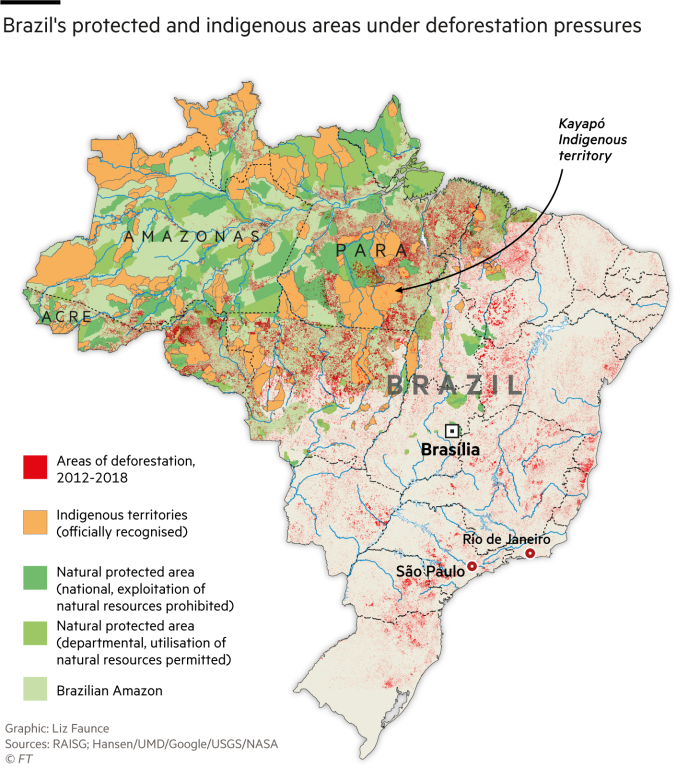

Nowhere is this truer than the Amazon basin, home to 1.7m indigenous people from 375 different groups, whose formally recognised territories account for almost a third of the area.

The challenges to these communities vary: illegal logging and mining in Peru, oil production in Ecuador, cattle-ranching in Brazil and coca cultivation for the drugs trade in Colombia.

Brazil’s deforestation has been well chronicled, but that in neighbouring Colombia is also severe. It lost 159,000 hectares to deforestation last year — a total hailed by the government as a success. In the previous two years the figures were higher.

In some parts of Colombia, indigenous communities have established businesses that are both environmentally friendly and commercially viable. These alleviate the financial pressure to use land for logging or other ecologically damaging purposes.

In the province of Cauca, for example, Colombian Coffee Connection (CCC) makes organic coffee sourced from farmers from the Nasa indigenous community and exports it to the US. The coffee’s tree-friendly credentials are one of its selling points.

The company’s founder Ervin Liz, himself a Nasa, says he has seen countless similar projects fail because local people lack business knowhow.

“This happens a lot in Colombia,” he says. “People think that all you need is a really good idea and it will sell like hot cakes. That’s not really the case. You have to know how to sell it.”

Other Nasa have made a virtue of Colombia’s most notorious cash crop — coca. Used as the raw material for cocaine, its cultivation is banned in Colombia except in indigenous communities, where it has long been used for medicinal purposes. One company, Coca Nasa, makes tea, wine, rum, flour, beauty products and a cola drink out of coca leaves.

But while these projects may be beneficial to those involved, they are small. CCC produces 500kg of coffee a month; Coca Nasa buys its coca leaves from artisanal farmers who grow just a few plants.

Elsewhere, though, indigenous communities are being empowered to safeguard significant tracts of land.

In Brazil, the Kayapó people — about 10,000 scattered across fewer than 50 settlements — have legal control of a swath of territory the size of Denmark. Some 1.3bn metric tonnes of carbon are stored on Kayapó land. It is made up of primary tropical forest and savannah and sits just outside an area known as “the arc of deforestation”, ravaged by illegal loggers and cattle-ranchers.

Until the late 20th century the Kayapó had no contact with the outside world. Now, Conservation International is helping them protect their lands and make a livelihood from honey, nuts, fruit and copaiba oil, a resin used in beauty products that can be drained from trees without cutting them down.

The project is financed via a trust fund. Set up in 2011 with an $8m donation, the interest generated by the investment — along with the sale of non-timber products — gives the Kayapó some financial security.

In Chocó, in north-west Colombia, a similar project seeks to develop a wild-forest economy to sustain the Afro-Colombian community. In an area where illegal mining and logging is rife, a company called Naidiseros del Pacifico runs the harvesting, processing and sale of açaí fruit — known locally as naidí. Partnerships for Forests (P4F), which oversees the project, says fruit collectors can make “as much as 131 per cent more income over a multiyear period than they could earn from illegal logging”.

By the end of this year, P4F hopes to have 56,000 hectares of Colombian forest — an area 10 times the size of Manhattan — under active, sustainable management.

In the Alto Mayo region of northern Peru, deforestation has been driven by coffee farmers who have chopped down trees to expand their plantations. But Conservation International has persuaded many of them to sign up to a rescue plan.

“We provide farmers with training that teaches them to produce organic, Fair Trade coffee,” says Sebastian Troëng, CI’s executive vice-president for conservation partnerships. “In exchange, they commit to halt deforestation.

Investing in Nature

The fight against climate change is a matter not just of cutting greenhouse gas emissions, but also of nurturing ecosystems that can draw carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Five more articles this week look at how business is rising to that challenge:

Why we need to declare a global climate emergency now

Business turns to nature to fight climate change

ESG investors wake up to biodiversity risk

“We were able to finance this project by demonstrating a fall in deforestation rates and turning that into certified carbon credits that can be sold.”

There are, of course, bad examples as well as good. Sometimes, countries have pursued reforestation too hastily in order to offset their carbon emissions. The monocultures that often result lack the biodiversity and resilience of the original ecosystem.

Instead, conservationists advocate “assisted natural generation” — using local labour and knowhow to help forests to grow back by themselves. Nikola Alexandre, a conservationist who has worked in Peru and Brazil, estimates that “230m hectares of degraded forest can be restored using this low-cost technique”. That is an area 10 times the size of the UK.

Such ideas are gaining traction as policymakers and investors start to pursue “nature-based” approaches to tackling climate change. A desire to “build back better” as the global economy reels from the coronavirus pandemic may provide further impetus.

“Political decision makers never want to change things when things are going well but when you have a crisis they are open to new ways of doing business,” Mr Troëng says. “I’m noticing greater receptivity in most countries to nature-based solutions.”

Comments