Iraq rediscovered, America uncovered - photography in Art Basel’s online viewing rooms

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

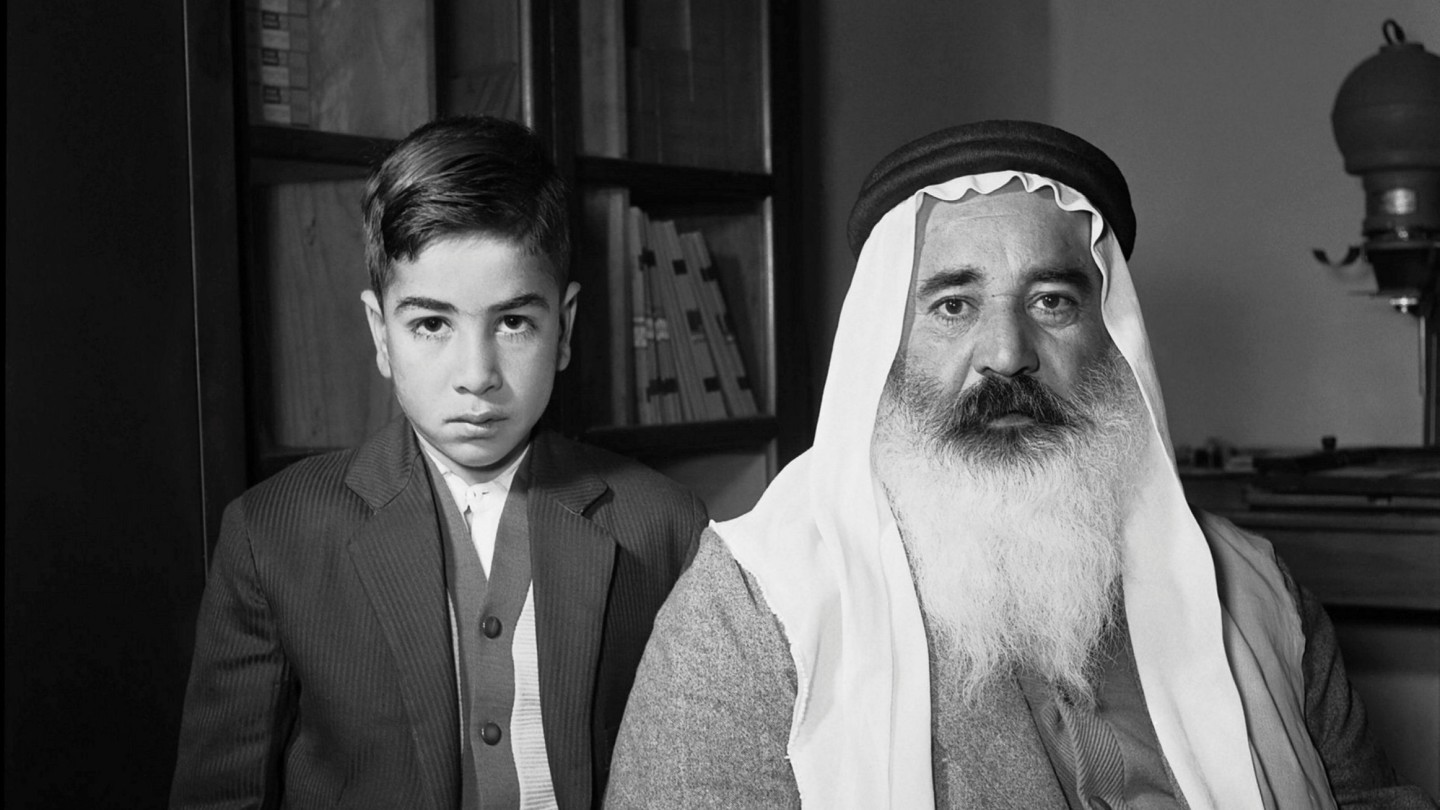

Few people had heard of Latif Al Ani until the Venice Biennale of 2015. But that summer, visitors to the Iraqi presentation in the elegant piano nobile of the Ca’ Dandolo, overlooking the Grand Canal, found a series of black and white images of a country strikingly different from the battle-riven Iraq of recent years.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Al Ani trained his cameras on a cosmopolitan society where trends and traditions, ethnicities and religions, seemed to mingle successfully. In Al Ani’s pictures, some taken professionally on behalf of the national petroleum company and the ministry of information, others personally, young Iraqi women Hula-Hoop in short white shorts, shepherds drive their flocks along newly tarmacked roads and freshly made suspension bridges glitter in the sun. He went up in light aircraft to take the first aerial shots of Iraq — the method as modern as the imagery — and professed to be the only person in the country who knew how to develop colour film.

And then he stopped. In absolute terms, Saddam Hussein had imposed a ban on taking photographs in public, but Al Ani, who had even accompanied Hussein to Paris as his official photographer, also lost faith as he saw his country falling apart, including when the Iran-Iraq war broke out in 1980. “I never thought,” he later said, “that Iraq would arrive at where it is today.” In 2003, much of his archive was destroyed in the American invasion.

Happily, however, some of Al Ani’s personal collection found its way to the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut — an organisation dedicated to tracking down and saving photography from the Middle East and north Africa — and has since come to the attention of Isabelle van den Eynde, a Dubai-based gallerist. She has chosen to show a selection next week, as a participant in Portals, Art Basel’s first curator-led online viewing rooms, which are accessible for VIPs from June 16 and for the general public from the day after.

The curators of Portals “gave us a brief about shifting times and the disconnected realities which have emerged from the events of the last year — the pandemic, social upheaval,” says Van Den Eynde, “and this is exactly what Al Ani is talking about. As he emphasises the natural beauty and elegance of his Iraq, you can’t help but think about what happened next.”

The art world is one of cycles, and the larger presence of photography at Art Basel is a perhaps a reflection of our times. A fair with an exclusively online format favours certain media, and photographic imagery translates well on the screen; sculpture not so much. Van Den Eynde is one of a number of galleries to bring monographic photography shows to their online rooms in response to the Portals agenda, with artists from high-profile Americans such as Catherine Opie and William Eggleston to lesser-known, younger names.

There is an economic angle too. “There are only a few photographers, like Andreas Gursky, whose work goes over the €500,000 mark,” says Thomas Zander, who has a gallery in Cologne, Germany, specialising in photography, “and the business of attending real-life art fairs for a gallery is a very expensive one. You need to recoup your outgoings and that means paintings.”

Online, though, galleries can afford to show work that commands less cash and which is also more adventurous. Take Joanna Piotrowska, a London-based Polish photographer in her mid-thirties, whom Zander is presenting — her work goes from €3,000 to €15,000.

She is already something of a superstar thanks to her black and white imagery, where unsettling narratives are embedded in both her domestic interiors and the body language of her young female protagonists. “The staying home, the confinement, the family ties and conflicts and potential violence she offers up in her work — it all relates absolutely to the current social climate,” says Zander. “If anything answered the brief, it was Joanna’s unique way of seeing the world.”

Explaining his decision to concentrate on lower-profile London artist John Murphy, who creates works out of found fragments — books, postcards, film stills and poetry, often presented in austere installations — Bernard Bouche says: “To me, he’s a highly intellectual and demanding artist who doesn’t conform to the current market trends. A digital fair is a good way to get a response from my collectors.” Not that Murphy would ever identify as a photographer, says Bouche, “though he sometimes uses the medium for his own conceptual ends.”

David Zwirner has chosen to focus on colour-saturated works from the 1970s and 1980s by Eggleston, and though you might consider Eggleston a living legend, Robert Goff, a director at Zwirner, is still finding new collectors. Eggleston’s explorations of the man-made American vernacular — the saturated hues of diner furniture, the scintillating tail fins of automobiles, the patent handbags and stiff perms of unsuspecting middle-aged women — have apparently developed a sprightly following in Hong Kong.

Photography is, of course, a highly malleable medium, a tool for its user and a conduit for subjectivity posing as truth: the days of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” are long gone. But nothing has better storytelling potential.

The new work at Lehmann Maupin from Opie, the Los Angeles-based artist who has delved into identity and American-ness through her 40-year career, bears witness to a year of trauma and change in the US. She does this through six elegiac landscapes of big country, grouped around an image of the statue of Confederate general Robert E Lee in Richmond, Virginia, graffitied in outrage following the death of George Floyd in May 2020.

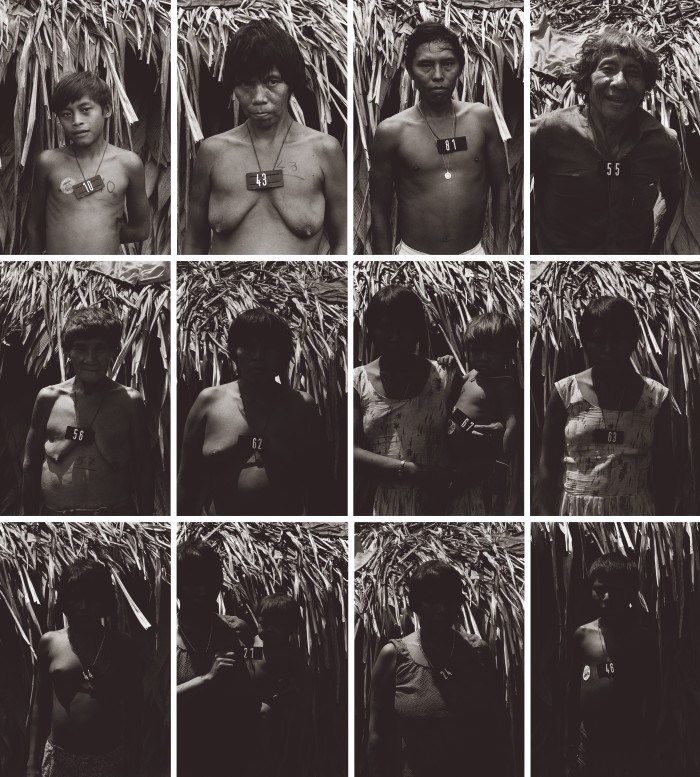

The work of Claudia Andujar, who since the 1970s has dedicated herself as photographer and activist to the defence of Brazil’s Yanomami tribe, is on show with São Paulo-based Vermelho and has taken on even more significance this year. The Yanomami’s earlier enemy — illegal mining — now has an invisible partner in Covid-19.

It’s all very post-pandemic, and even in the context of an online art fair, there seems to be a sliver of space to contemplate current concerns.

June 17-19, artbasel.com

Comments