How I Spend It: Maurizio Cattelan on the magnetic attraction of flags

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Going to school in Padua, Italy, when I was a child, meant to stand for the national flag. There was one waving on every school façade, every public sports facility, and all official buildings. At some point, every child would receive an atlas for Christmas, in which you’d get lost by looking at the hundreds of coloured rectangular shapes. Flags are like ideas: they look different, but in the end they are all the same.

The first time I really noticed one was when I saw it waving at half-mast. How can a symbol of power become so tragic, I kept asking myself; how can you turn something so venerated into something so friable with a simple gesture?

Some might think that it would be my dream to design a flag, an icon that survives the generations; is looked at with respect as it waves during sport events and official celebrations; and is replicated thousands of times. But artists are not made for flags.

Flags are conceived to be untouchable, and so they bear a power that is huge on one end, and very fragile on the other. That’s probably why very few artists have challenged the image of a flag – and I am not one of them. Jasper Johns and David Hammons have broken the high and solid wall of art visibility, and accessed a much larger audience by humanising the act of flag-making, and redefining the true colours of American identity – but these are exceptional cases. Most of us cannot even think of the flag as something truly modifiable.

We take flags for granted, we never interrogate them, and we rarely understand the sometimes cruel symbolism that lies behind the choice of a colour, the design, the decor. Take the Italian flag: did you know it was designed by Napoleon to mimic the French flag, and the green was picked because it was his personal favourite? Or, did you know that there’s only one flag in the world with a representation of humans (Belize) but four with images of firearms (Mozambique, Bolivia, Haiti, Guatemala)?

I love the fun (and less fun) facts about flags: the flag of Paraguay has two different sides; the Filipino flag is flown with the red stripe up in times of war and blue stripe up in times of peace; France used to have a completely white flag for about 15 years of its history; and two almost identical flags actually do exist: Monaco and Indonesia. (The only difference is their proportions.) You can’t change a flag; but sometimes you do. Danes have kept theirs since 1219, but Afghanistan has changed its flag more than 20 times in the past hundred years, and New Zealanders have tried to take the Union Jack out of theirs through a referendum, which was finally rejected in 2016.

Flags are a memory of our history and a projection into our future, and therefore should be looked at with the same amount of respect and suspicion. And as with anything else in life, I am magnetically attracted to what I don’t understand, or what I dislike.

Through these conflicts I’ve learned that the real power of images lies in frictions, and struggles, and doubts: flags don’t accept mistakes, they only shout their truth. But truth is so hard to tell, and it sometimes needs fiction to make it plausible.

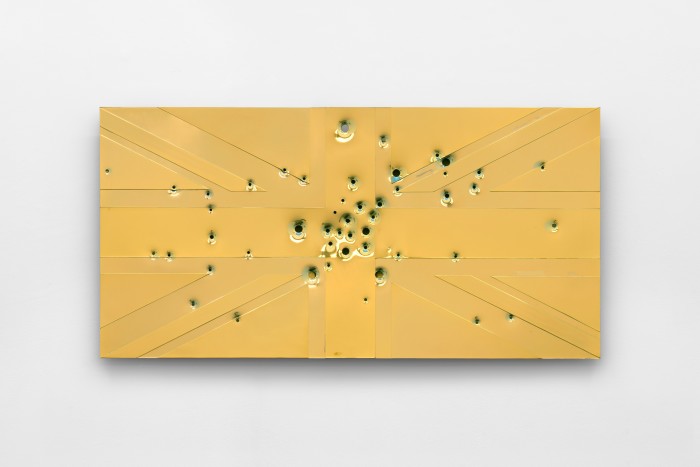

Maurizio Cattelan’s latest work, TEARS, inspired by the Union Jack, was presented by Massimo De Carlo at TEFAF Online. massimodecarlo.com

Comments