The magic of Stonehenge

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The British sculptor Henry Moore first saw Stonehenge on a clear and silvery night in the autumn of 1921. Bathed in lunar light, the majesty of the standing stones appeared magnified to the Royal College of Art student, still fresh from the terrors of the first world war trenches. “Moonlight, as you know, enlarges everything,” he said. “And the mysterious depths and distances made it feel enormous.”

“From that moment on, Stonehenge was always in his psyche, just as it is forever embedded in the English psyche,” says the artist’s daughter, Mary Moore. More than a century later – and a mere 30 minutes down the A303 – she has collaborated with Hannah Higham of the Henry Moore Foundation on an exhibition presented by Hauser & Wirth Somerset that throws the influence of Stonehenge on the sculptor into sharp relief. For Mary, there’s a direct line to be drawn between the ancient megaliths of the Wiltshire Chalkland and the modern abstractions hewn by her father – part of his life-long assimilation of more than 30,000 years of visual art.

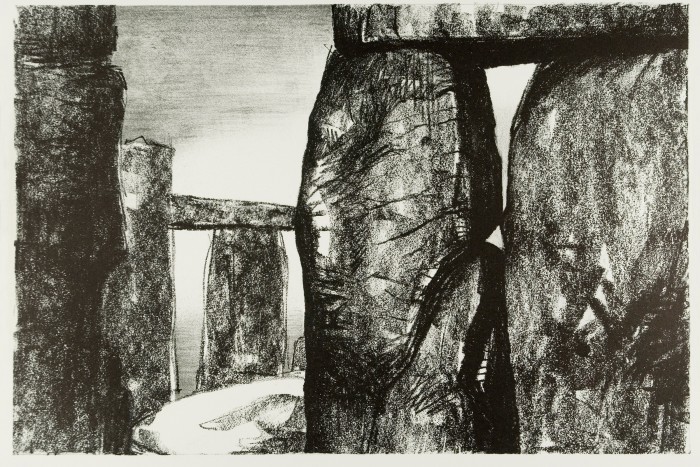

From a darkly ethereal series of 1970s lithographs that depict Stonehenge in blackened hues to a quartet of vast bronze renderings of monoliths known as the “Upright Motives”, many of the works on display at Henry Moore: Sharing Form (28 May-4 September) feel like the culmination of Moore’s first solitary night at the henge. For the son of a miner who often worked outside and spent his life carving with English stone – from granite to Hopton-Wood to Cumberland alabaster – these rocks held the power to root humankind, deeply and directly, to the earth. “In his sculpture, the landscape and the human body are totally interchangeable,” says Mary Moore. “Just as they were in the minds of our ancestors; it’s all part of the great circle of life.”

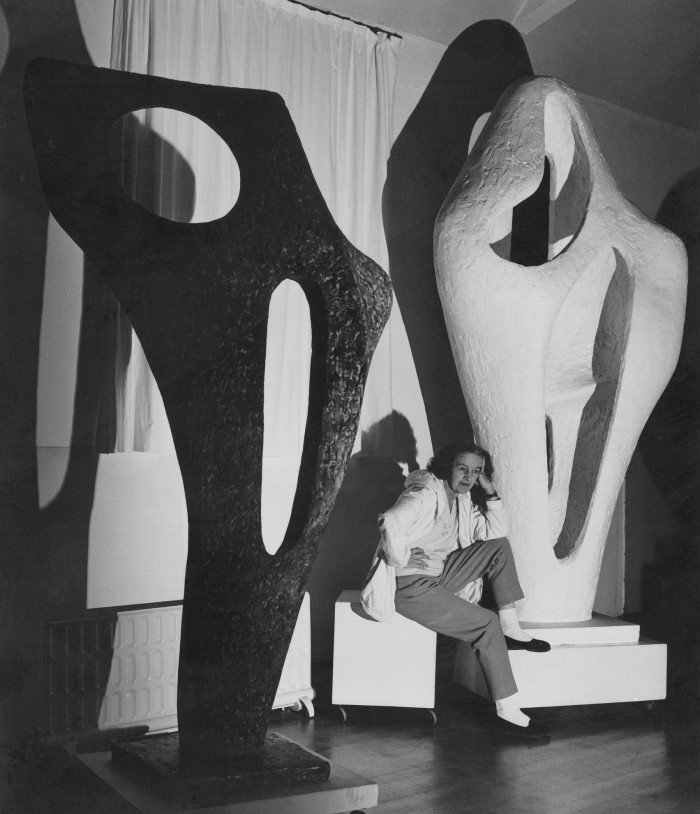

Ancient stones have long imprinted themselves on the artistic community. Moore’s friend and contemporary Barbara Hepworth was similarly captivated by the sanctity of Stonehenge – and some of the more than 1,300 stone circles and monuments that are scattered across Britain, Ireland and Brittany. In 1937, both artists contributed to “Circle”, a survey of constructivist art, which saw Hepworth’s essay illustrated by photographs of Stonehenge by Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius. For Eleanor Clayton, a Hepworth specialist and author of Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life (which accompanies a survey of her work travelling to Tate St Ives later this year), it’s no coincidence that they were especially attracted to the ancient site. In times of war, she says, it became a beacon of hope and continuity for them, as well as a wider reflection of the holistic, three-dimensional way they experienced the world.

“For Hepworth, who called herself ‘a pagan at heart’, these neolithic stones show that sculpture can have a communal importance,” says Clayton. “Stonehenge becomes evidence that it should have an integral place and purpose in society. For her, the sculptural, the societal and the spiritual were all completely one and the same thing.”

That so much significance can be ascribed to this gargantuan gathering of rocks is perhaps as compelling as the story of the stones themselves. According to The World of Stonehenge, an exhibition at the British Museum (until 17 July) presenting the site through the prism of more than 430 contemporaneous objects drawn from regional museums across Europe and the UK, it took more than 1,000 years to assemble the 20-25-tonne, up-to-5m blocks of sarsen stone into their celebrated solstice-aligned configuration. Rather than being built by the druids, as was long believed, it is now thought to have been constructed much earlier, in the days of the Sphinx.

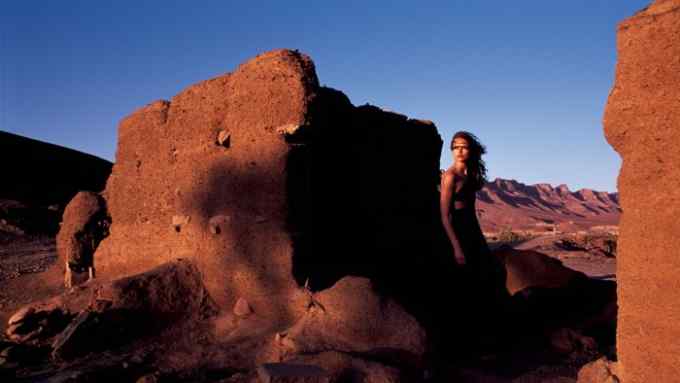

Some 4,500 years later, there has been a renewed interest in this and other standing stones among contemporary artists. Clayton points to the work of Ro Robertson, whose investigations of stone monuments and rock formations initiate conversations around queer identity and gender norms – the idea being that even the perceived solidity of rock shifts and evolves over time. Or the British artist Emii Alrai, whose latest installation, A Core of Scar (at Hepworth Wakefield until 7 September), comprises two 5m and one 2m-long timber-framed sculptures clad in polystyrene, plaster, sand and pigment, and decorated with glass vessels inspired by funerary urns. Alrai says she was drawn to the “powerful aura of the past” ignited at sites including the Devil’s Arrows – a trio of huge, and rather neglected, standing stones outside Boroughbridge in North Yorkshire, and the Nine Maidens megaliths in Cornwall.

“These rocks hold so much of the narrative and memory of time, how we as a civilisation have developed and where it all began,” she says. “When you look at these monoliths, you’re able to connect to something very ancient because of our collective understanding of them. We experience that in a very physical way.” Drawing on her own Iraqi heritage, Alrai links the British geological landscape, where stones are erratically moved or displaced and rock faces ruptured, with the diaspora experience and what she calls “the histories we embody”.

Friends Lally MacBeth and Matthew Shaw conjured the concept of Stone Club – “a club for people who like stones” – while walking on the Penwith Moors in Cornwall last year. Members are furnished with badges and newsletters with information about curated events that include film screenings and festival-like gatherings, as well collective walks in and around ancient sites. Since setting up in November, they’ve picked up close to 1,000 members – largely urban dwellers. “Stones are the first markers that connect us back to our ancestors,” says Shaw. “These sites tell us a lot about ourselves and our local communities.” Similarly brilliant and cultish in its appeal is Weird Walk, an independent zine dedicated to the folkloric stories and fantastical imaginings ignited by ambling along Britain’s ancient paths.

For the British artist Jeremy Deller, whose name has long been synonymous with Stonehenge, the site remains the ultimate soothsayer. “When we’re talking about it, we’re really talking about ourselves,” he says. “It’s this symbol of us – whoever we are – and a symbol of modern Britain.” It’s a decade since Deller first inflated Sacrilege, a full-scale bouncy castle replica of the monument, hosted in locations across the globe to the universal delight of children (it’s currently residing at the Oakley Court hotel in Berkshire for the remainder of the summer).

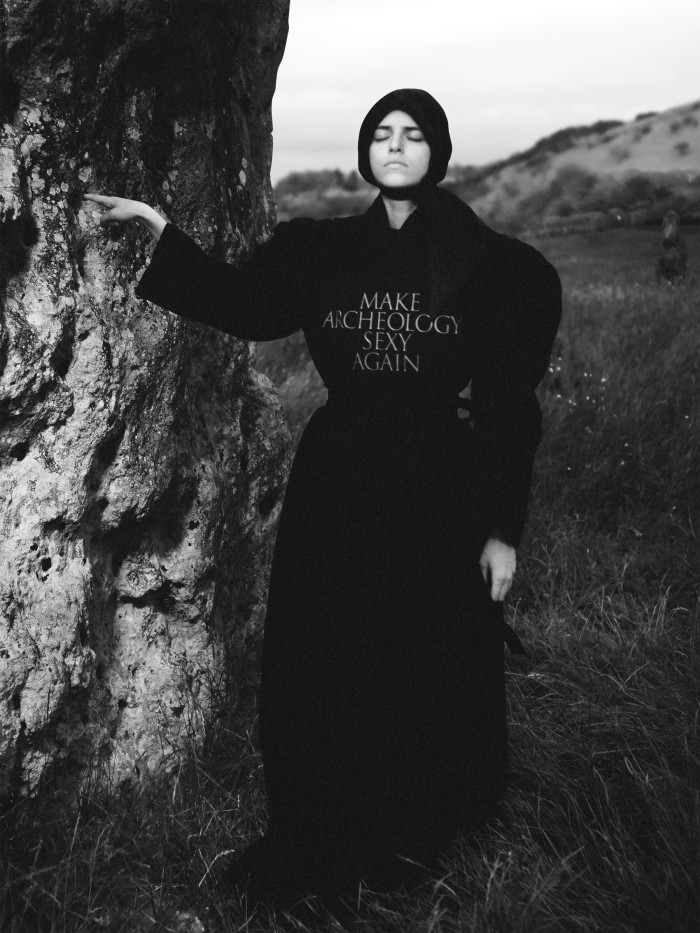

In 2019, Deller collaborated with Sofia Prantera, the designer behind the London streetwear label Aries, on what he considers to be the perfect amalgamation of English heritage and fashion. “Stonehenge always feels relevant. To me, it’s the most contemporary structure in the United Kingdom,” says the artist, who is co-curating a midsummer solstice celebration at the British Museum that will include music, film, performance and talks as part of a late-night opening of its Stonehenge show (Solstice Late, 17 June). Works from his Wiltshire B4 Christ collaboration with Prantera are also included in Radical Landscapes (Tate Liverpool, until 4 September), a show that cleverly weaves themes of identity and activism into landscape art, and puts Stonehenge at the epicentre of ongoing political debates about civil liberties and freedom to roam.

Why does Deller think the henge continues to hold our attention? “Stonehenge represents our attempt at finding our way out of whatever current mess we find ourselves in, to recalibrate our values and ideas,” he says. What could be more optimistic – or necessary – than that?

Comments