Venice exhibition restores African architects to the story of Tropical Modernism

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

If you want a sense of Modernist African architecture, a stroll around Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, Ghana, is a good start. A citadel surrounded by lush greenery on the edge of the city, the campus is home to a number of Ghana’s most noteworthy Modernist buildings, such as the open-sided Great Hall with its exposed staircases and the imposing blocks of Unity and Africa Halls.

In keeping with the Architecture Biennale’s focus on African and diasporic culture, a flavour of west Africa comes to Venice this month: inside the Applied Arts Pavilion is a 30-minute video chronicling Tropical Modernism. The video features interviews with Ghanaian Modernist architect John Owusu Addo and Samia Nkrumah, politician and daughter of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah; archival footage of the colonial Gold Coast, its haunting castles and forts on the coast; and the sweet guitar riffs and singing saxophone of highlife music. Organised by the Biennale and London’s V&A Museum in collaboration with KNUST and the Architectural Association (AA), the exhibition, which includes a 35-metre-long brise soleil (sun shade), photographs and plans, offers critical nuance to lesser-known parts of architecture’s narrative.

Tropical Modernism can be found from Sri Lanka to Morocco, Zambia to Ivory Coast. Its development is closely tied to the history of colonialism: after the second world war, architects who had honed Modernist ideas in Europe headed for their empires’ territories in Africa and Asia. Countries in Africa in particular became an “experimental ground” for European architects, says Ghanaian architect and historian Kojo Derban. He adds that the postwar rise of the Commonwealth — an organisation of the UK and British colonies, many either newly independent or campaigning for independence — was also responsible: “A lot of those architects found their way through the Commonwealth Office into the colonies and positioned themselves as architectural firms.”

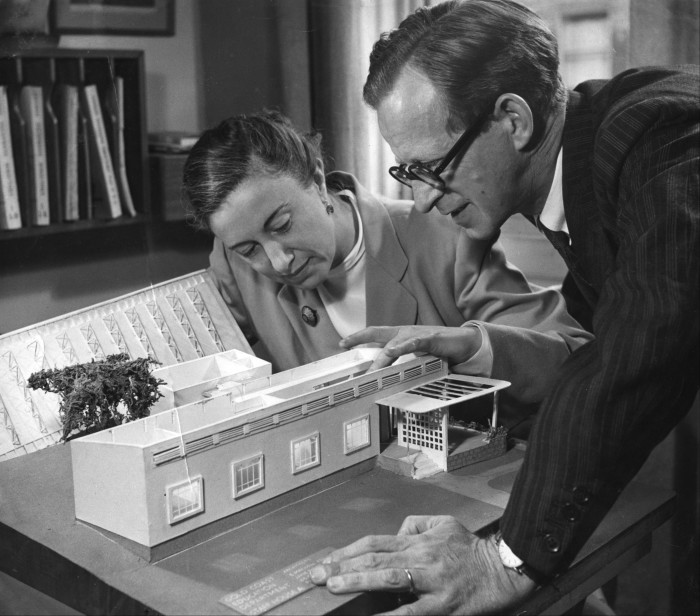

Until now, architectural historians have focused primarily on European architects working in Africa, such as Britons Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew. But the Venice show illuminates how architects from the continent were at the forefront of innovation too. Alongside the likes of Fry and Drew, says Nana Biamah-Ofosu, researcher and architect at the AA and co-curator of Tropical Modernism, “there are Ghanaian architects, west African architects, who were significant in the development of this architecture, whose voices are missing from the archive.”

One example is Samuel Opare Larbi, who was trained at the AA in London from 1963, including its School of Tropical Studies. On his return to Ghana in 1969, Larbi joined the department of architecture at KNUST and went on to design Kumasi’s National Cultural Center and the Kumasi head office of the Bank of Ghana.

Indeed, despite claims to the contrary, the European architects definitely had local input. Traditional and pre-colonial building practices — especially when it comes to temperature regulation — were highly influential. “I would argue this is the way the Africans that they came to meet were already building,” says Kuukuwa Manful, a postdoctoral researcher at Soas, University of London, “the standard format of the single bank of rooms, and the verandas. When you look at traditional Asante architecture this is what it is.”

After Ghana gained independence from the British in 1957, a number of public buildings such as the Ghana International Trade Fair Centre in Accra — by Ghana’s Victor Adegbite and Polish architects Jacek Chyrosz and Stanisław Rymaszewski — were built in the style. Later came many of the notable structures on the KNUST campus designed by Addo; in the Senior Staff Club House (1964), his brise-soleil design casts shadows on the outside courtyard. An architectural approach that had been closely associated with colonial rule was, under the rule of Kwame Nkrumah, a symbol of the new, independent Africa.

“A late imperial architecture . . . suddenly becomes [Ghanaian], through Nkrumah’s Africanisation policy,” says the V&A’s Christopher Turner, who has curated the exhibition alongside Biamah-Ofosu and Bushra Mohamed, also a researcher and architect at the AA. Drawing parallels with the highlife music that plays throughout the video, Turner points to the words of Ghana’s “king of highlife”, ET Mensah. “He said that highlife music was indigenous music played with foreign instruments, and that happened with architecture too.”

Tropical Modernism still has much to teach in an era of decolonisation and decarbonisation, both big themes at this year’s Biennale. This is “climatically responsive architecture”, says Biamah-Ofosu. For example, Fry and Drew oriented buildings east-west, so when the sun rose it travelled directly over the spine of the roofs (which themselves contained a cooling cushion of air), protecting the rooms from its full glare.

Yet whether these designs continue to have an important place in Ghana itself is an open question. While some buildings hold their prestige, developments have moved away from the Tropical Modernist aesthetic towards more globally modern architecture. Manful observes indifference to these structures. “[The buildings] are also symbols of a particular time, these colonial people coming in and lording over them. And even after independence the new African leaders were following in the same footsteps and lording over them, so there’s not that kind of affection with these buildings.”

And Manful is wry about the west’s fascination with Tropical Modernism: it is “to some extent a preoccupation of activities of white people in Africa”, she suggests. “I’m more concerned with building how Africans build and live rather than how we think they should based on these styles that we think are big moments in our history.”

Nonetheless, Mohamed argues that Tropical Modernism is a part of the story of African architecture that shouldn’t be neglected. “It’s important to understand the past to influence the future,” she says.

‘Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa’ is in the Arsenale until November 26

Comments