Extinction crisis: how can we end the illegal wildlife trade?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

You don’t see the scar at first. But when Boldbaatar Naranbadrakh turns his head to the left, the two jagged dimples become obvious. One night in 2000, as he was returning home from work as a customs official in northern Mongolia, a stranger stabbed him in the neck.

Naranbadrakh had just intercepted an illegal shipment of 17,000 marmot furs headed across the border to Russia. He has no doubt that the attack was the smugglers’ “revenge”.

Naranbadrakh was undeterred by the assault. He is now fighting wildlife trafficking from a different angle — as head of Mongolia’s unit for training sniffer dogs. On the outskirts of the capital Ulan Bator, two dozen dogs sit in outdoor cages, the water in their bowls frozen by the cold weather.

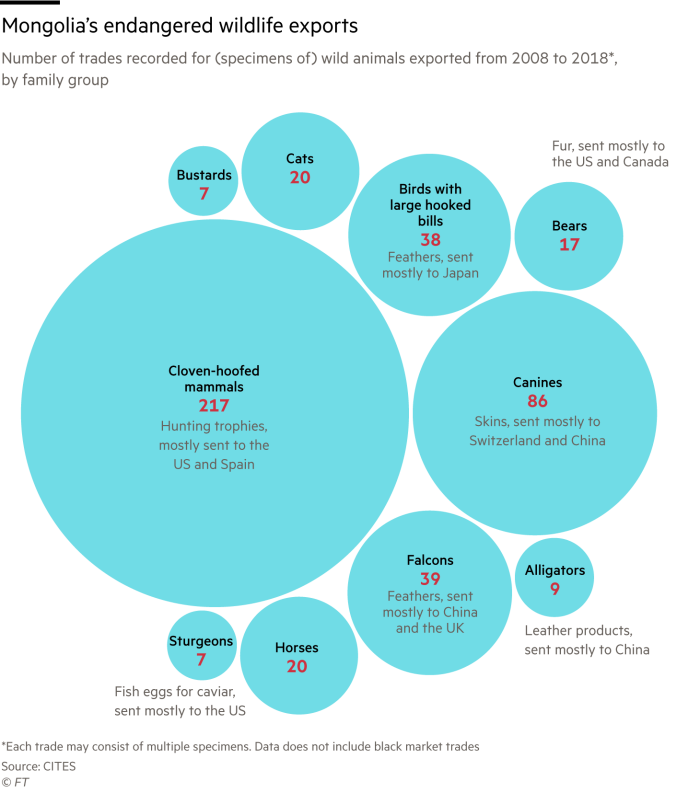

If Mongolia is to stem the flow of precious wildlife parts, these dogs are one of its best bets. The animals are experts at detecting wolf teeth, bear paws, snow-leopard skins and deer antlers.

This summer, one even detected a shipment of 49,000 bullets at Ulan Bator’s railway port. The ammunition, which came from the US, was almost certainly intended for hunting.

Unfortunately, Mongolia has just 34 customs sniffer dogs to cover a territory the size of France, Germany and Spain combined. Naranbadrakh wants to double that number, but to do the work properly he says it would need to double again — to about 150. Meanwhile Mongolia, which has in the recent past been a hub for the illegal wildlife trade, can only expect to intercept a fraction of the illicit shipments.

Here is the fundamental imbalance: animals, whose long-term survival in the wild is almost priceless, are reduced to whatever product can generate immediate cash — fur, meat, dubious medicine. And while enforcement agencies struggle, often heroically, on scant resources, a small group of poachers and dealers generate large profits.

Worldwide, wildlife worth between $7bn and $23bn is trafficked each year, according to a 2016 joint report from Interpol and the UN Environment Programme. Rhino horns and elephant tusks are the best-known examples but the industry stretches to other much-loved species — turtles, otters, songbirds — as well as fish and plants.

“We’re facing huge losses,” says Andrew Terry, director of conservation and policy at the Zoological Society of London, the conservation charity. “You almost have to either be a researcher, work for a zoo, or be an illegal collector to know what some of these species are. A lot of species are just disappearing without anyone really knowing.”

ZSL, the owner of London Zoo and the FT’s Seasonal Appeal partner for 2019, has made tackling the illegal trade a key priority. Along with the UK Border Force, it has helped to train Mongolia’s sniffer dog teams.

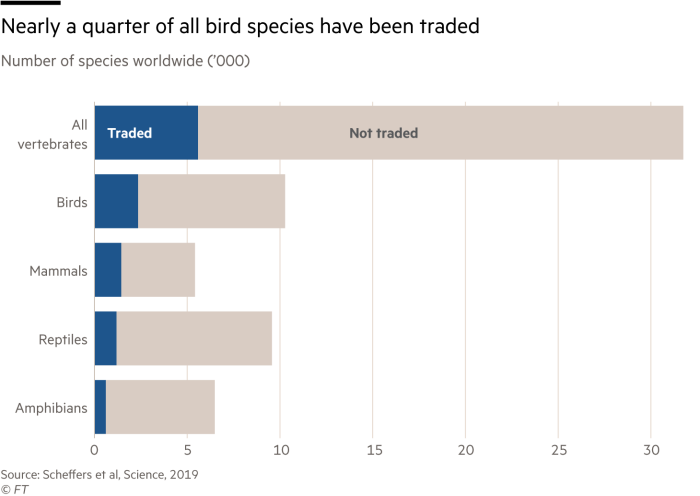

More than 5,500 vertebrate species — one in six of the total — are traded internationally, according to a recent paper in the journal Science. For mammals, the proportion is one in four. The animals are traded alive and dead, whole and in pieces, by legal operations, criminal gangs and opportunistic individuals.

For many species, it’s a fast track to extinction. Even those that are unlikely to die out imminently, such as Mongolia’s marmots, are seeing their numbers cut dramatically. That knocks ecosystems off balance and leaves the species vulnerable to outbreaks of disease or changes in climate.

“This is the great emptying,” says ZSL’s Terry. “We just don’t have any frame of reference any more to the great aggregations of wildlife — whether it was massive fish stocks or huge bird populations — that you would have seen even 50 years ago.” As creatures become scarcer, basic economics kicks in, and prices spiral. Some collectors will pay $50,000 for rare tortoises to be kept as pets.

Poachers also find substitutes: Asian pangolins — anteaters prized for their meat and scales — have been pushed to the brink, so African pangolins have been hunted instead. The tiger trade has been squeezed, so poachers have supplied lion and snow-leopard bones for use in Chinese traditional medicine.

The Science paper estimates that a further 3,200 species could be traded in the future, because they have similar characteristics to those sold today. In total, the authors say, that makes 8,775 species at risk of extinction from trade.

We arrive at the Ulan Bator’s main outdoor market with representatives of ZSL. It is dusk, and many stalls have closed for the day. Nonetheless, within three minutes, we find a young man selling wildlife. He drags out a large black holdall, from which he pulls a steppe eagle’s talons — then its severed head.

You shouldn’t find a steppe eagle in Mongolia in winter. At this time of year, the birds migrate south — often thousands of miles over the Himalayas, to the warmth of the Middle East or Africa. (Russian scientists recently abandoned an experiment to track a group of the birds, after one flew to Iran and their SMS transmitters ran up hundreds of pounds in roaming charges.)

Steppe eagle numbers have fallen so sharply that they are now considered endangered by the International Union of Conservation of Nature. In the wild, they are magnificent birds, with a two-metre wingspan. In the market, the eyes and yellow beak are as bright as in a nature documentary. But the head lacks the beauty, the spirit of a live animal. It is divorced from the natural world.

The trader also produces wolf teeth — ours for 70,000 tugrik ($26) each. He claims to have a whole eagle nearby, stuffed, available for 450,000 tugrik. Needless to say, there are no certificates of origin, as are required for sale by Mongolian law. But the trader shows no fear of being caught. As he stuffs the eagle head back into the bag, he just seems surprised that we aren’t buying.

Wildlife trafficking exists on every continent: in the UK, France and the US, criminals have been taking millions of baby glass eels from rivers and smuggling them to China, where they are farmed for a prized food. Last month, a man in Wales pleaded guilty to selling endangered animal specimens, including primate skulls, on eBay.

The internet not only helps dealers to sell animals: it also means that they can contact poachers thousands of miles away, cutting out middlemen and reducing the chances of detection.

Yet the problem is often most severe in those countries where corruption, widespread hunting and weak enforcement combine. In Mongolia’s case, the dynamics changed fundamentally in the 1990s. The country had been a Soviet satellite state, exporting furs and meat to the USSR. Schoolchildren were even tasked with trapping a set number of squirrels during the summer holidays, as a bizarre form of homework.

But there was some regulation, limiting the damage to wild populations. Then, in the chaotic days after the collapse of communism, hunting became a free-for-all. Mongolians killed more animals — and more species — than ever before. This was enabled by the relaxation of gun laws and the disintegration of law enforcement.

At the same time, a major new customer emerged: China. Chinese buyers would pay 50 times as much for wolf and marmot skins as the USSR had, and there was also the country’s booming market for traditional medicine. By 2006 Mongolia’s wildlife trade was estimated at $100m a year; a third of Mongolian men said that they were active hunters. Numbers of red deer, which had grazed near the capital, fell more than 90 per cent between 1986 and 2004. Marmots declined 75 per cent in little more than a decade; numbers of wild argali, the world’s largest sheep, fell a similar proportion between 1975 and 2001.

Belatedly, Mongolia’s government cracked down. In September 2016, it finally become illegal to possess trafficked wildlife — such as snow-leopard skins. Such measures have helped to push the trade underground but it endures, even in the heart of Ulan Bator.

Any visitor to Mongolia quickly realises that this country is different. It has the world’s coldest capital city (the average temperature in January is minus 22C), and also one of the most polluted (because residents burn coal to keep warm). It is also the emptiest country in the world. Mongolia has five people per square mile: by comparison, Russia has 23, the US has about 90 and the UK has more than 700.

The lack of humans has not created a haven for wildlife. That is partly because of the vicious climate, partly because of hunting and partly because of the huge growth in livestock. In the three decades to 1989, the number of cows, camels, goats, sheep and horses in Mongolia was roughly steady at around 23 million. Since then, the number has nearly tripled — to 66 million.

Livestock compete for grazing land with wild animals, such as Mongolian gazelles and argali sheep. They also make herders see predators, such as wolves and snow leopards, as pests to be eradicated. In the harsh Mongolian climate, there is little room to view wild animals sentimentally.

That makes life tough for conservationists, who want to raise awareness of how close to the edge some species are in Mongolia. There are now fewer than 40 Gobi bears — a subspecies of brown bear that lives in the Gobi desert. The wild Bactrian camel, which lives in the Gobi desert in south Mongolia, as well as in China, is below 950 individuals and rated critically endangered. Even marmots — large squirrels with an estimated population of 20 million in 1990 — have fallen so sharply in number that there is now a nationwide ban on hunting them.

The journey from Ulan Bator to the Chinese border cuts through the steppe, a fenceless expanse of pastureland, on which there is barely a tree in sight. We pass coal mines and herds of camels, horses, sheep, cows and goats. In the Gobi, the occasional gazelle and falcon cross our path. We turn off the main road into a small nature reserve, and catch sight of a cluster of argali — famous for its horns — perched on a rocky outcrop. However, the sense is that wildlife has been pushed to the edge.

“Wolves used to run next to the road when you were driving,” says Battur Ganbaatar, who lives near the border town of Zamiin-Uud. “There are many fewer wolves and lynx these days . . . I feel the pain — that you look and there are no animals.” Ganbaatar used to serve in the army, when the men would shoot gazelles for food. He gave up recreational hunting in 2004, after a fortune-teller told him he had taken too many lives and should stop. “I tell my son, never hunt, because I already hunted enough on your behalf.”

But Ganbaatar laughs at the suggestion that hunting, associated with masculinity in Mongolia, could be eliminated entirely. And he points out that if he were to wander across the steppe to shoot animals, no one would stop him. That places a huge responsibility on the legal authorities.

Zamiin-Uud handles much of Mongolia’s trade. At its peak, the customs point deals with 400 lorries and 2,000 passenger vehicles — many of them filled with day trippers buying goods in China. It is immediately obvious how little is inspected. There are meant to be four sniffer dogs here.

On the day we arrive, one has recently died. So there are three that rotate round a 24-hour shift at the vehicle checkpoint. At other border checkpoints, wildlife parts and meat have been found stowed inside coal trucks. Even if corruption were not an issue — Transparency International ranks Mongolia 93rd out of 180 — smugglers would fancy their chances.

Wildlife parts are tricky because they are so small. In April, searching a car, a sniffer dog found that a Mongolian man had four pieces of freshly killed deer tail cling-filmed to his stomach, while his companion had three bear teeth stuffed in his sock. The men “started breathing heavily and then they panicked”, recounts Uuganbayar Gereltsogt, 34, who joined the force because he liked his brother’s uniform. “They said they had been offered 500 yuan to take the items across the border.” Gereltsogt is used to traffickers’ pleadings. “People say, ‘Let me free — I will take the items back to Mongolia.’ I say, ‘You’re in the control zone, I have to confiscate the items.’”

There is no reliable way to estimate how much of Mongolia’s illegal wildlife trade is intercepted. Detecting shipments requires not only patience and luck, but an ability to identify rare species. The sniffer dogs have limits: they cannot inspect the tops of lorries, for example.

ZSL, which has been fighting trafficking in Mongolia since 2013, has tried to incentivise handlers, by introducing an award for the customs official who detects most illegal wildlife. “If I’m with my dog, I’m 100 per cent sure I can stop every potential smuggler,” says Munkhnasan Yadamsuren, the first recipient of the award.

Yadamsuren worked at Zamiin-Uud, where most of those he stopped were Chinese citizens. “The Chinese have a hunger for wildlife products and stones,” he says. One shipment comprised 4,000 marmot skins. “How could people kill 4,000 animals just for money? My heart aches.”

ZSL is also working to build community support for tackling illegal hunting, and to train local law enforcement in how to spot the problem. At a forum it organised for community police officers, suspicion of China is evident. Mongolians fear that China’s long-term plan is to control Mongolia, as the Qing dynasty did for centuries. (Modern China includes Inner Mongolia, which is home to more ethnic Mongolians than Mongolia itself.)

They blame China for pushing up the price of food: although meat exports are banned, smugglers have been found taking carcasses across the border, where the prices are more than double. They cite YouTube videos showing Chinese people mistreating animals. But there is an acceptance too that the solution to excessive hunting lies with Mongolians themselves. “It’s a mindset,” says one woman. “People need to be made much more aware that it’s not OK to do this.” A man says that there is no “ecological balance”. “It’s very easy to hunt — jeeps, guns,” he sighs.

Many Mongolians still value wild animals mostly for their parts. Dalmatian pelican beaks are used to scrape the sweat from racehorses, in the belief that the bird’s speed might rub off on the horses. Wolves’ ankle bones are deemed to bring good luck while their meat is believed to be medicinal: the brain is supposed to guard against Alzheimer’s, the tongue to fight respiratory diseases.

“When you hunt a wolf, nothing is wasted,” says Dugersuren Erdenebileg, 29, who herds camels near the border with China. “My little sister had pneumonia, and my mother gave her meat patties from the wolf. Afterwards my sister didn’t have any problems with her lungs.”

Perhaps the biggest question that conservationists face as they tackle wildlife trafficking is what trade should be allowed. Would legalising the sale of products such as ivory undercut the poachers, and give incentives for local people to protect wildlife? Or would it legitimise the products in the eyes of consumers, and allow illegally harvested animals to be laundered into the legal market?

These divisions came to the fore in August, at a meeting of the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites), the international forum for regulating wildlife trade. Cites decides by consensus which species should not be traded and which should be subject to strict limits.

Southern African countries, led by Botswana, pushed — unsuccessfully — to allow ivory stockpiles to be sold legally. East African countries are opposed to any international ivory trade. Prohibition has so far won out in China too, which implemented a ban on domestic sales of ivory last year.

“Conservationists are somewhat conservative as a field, and we’re all very concerned that we could set in motion a series of steps that we just can’t control,” says Terry of ZSL, which is nonetheless open to the idea that establishing a legal trade could help in some contexts.

Gradually, concern at the illegal wildlife trade has bubbled to the highest levels. In the UK, Prince William and prime minister Boris Johnson have both championed the issue. The UK has so far spent £23m from its aid budget on tackling wildlife crime in countries, particularly in southern Africa. And at an October 2018 conference in London, 65 countries — including Mongolia — declared that the illegal wildlife trade was a “sophisticated criminal activity” that represented a “great threat to national and regional security”, because it often used the same networks that supported money-laundering, weapons and drugs.

The link with organised crime has helped to galvanise companies, including tech platforms such as Facebook and Alibaba, where products are advertised and sold, and banks, which might process the proceeds. “We’re seeing a lot more interest from the financial sector in trying to tackle money laundering,” says Richard Thomas, head of communications for Traffic, a charity fighting the illegal wildlife trade. Among the other proposals agreed at the conference was a new focus on reducing demands for illegal wildlife — such as Chinese medicine. “We know that [reducing demand] is the prize,” says Terry.

Overall, wildlife trafficking is “a governance issue”, said the World Bank in a report published last month. “Solutions are known [but] global attention and resources appear insufficient.” International funding for tackling the illegal wildlife trade in Africa and Asia has averaged only about $260m a year — much less, compared with the size of the problem, than is devoted to the illegal drug trade.

Safeguarding animals from trafficking — and extinction — requires, for example, conservation areas that also generate income for local communities. “We tend to think climate change is an issue, and habitat loss is an issue, and illegal trade is an issue,” says Terry. “The problem is they’re not independent — they’re exacerbating each other, creating these tipping points.”

In Mongolia, information on many animal species is lacking or outdated. The fear is that, given what has been lost already due to the increase in livestock, even small further losses from hunting could be crucial. There are only around 3,800 saiga antelope left in the country, according to the government. The saiga, a critically endangered species whose horn is used in Chinese medicine, have in the past suffered mass die-offs due to disease. Snow leopards, whose numbers in Mongolia are estimated at below 1,200, are also used in Chinese medicine.

“Poaching snow leopards — for fur and bones — is still happening,” says Bayarjargal Agvaantseren, director of the Snow Leopard Conservation Foundation, which has succeeded in carving out a protected area for the cats, despite pressure from mining companies.

Prosecutions for illegal hunting remain rare, partly because the crime is so difficult to detect. In January, Mongolia is due to start recruiting a force of 170 so-called eco-police, who will be deployed to remote areas. However, their remit will include other environmental offences, such as illegal mining and illegal forestry. Customs, too, has other priorities — such as stopping a rising flow of drugs into the country, including cocaine sent via courier from Europe.

At the sniffer dog centre, the handlers say that they have already benefited from the UK Border Force’s training. While previous practice — a hangover from Mongolia’s Soviet-influenced days — was to micromanage the dogs, the new approach encourages the handlers to trust in the dogs’ decisions.

Nonetheless, there is a realism about what the country can achieve. “Because we have such a big territory, and we have neighbours that are in constant demand, it will take some time. We can’t end the illegal wildlife trade in a few years,” says Naranbadrakh, the customs official who was stabbed in 2000.

Could an attack like the one that scarred him happen today? Naranbadrakh nods: “It could. There’s money involved.”

Henry Mance is the FT’s chief features writer

Some names have been changed since publication to improve transliteration accuracy.

• How you can help

Please help us support ZSL’s urgent work by making a donation to the FT’s Seasonal Appeal. Click here to donate now

If you are a UK resident and you donate before December 31, the amount you give will be matched by the UK government – up to £2m. This fund-matching will help communities in Nepal and Kenya build sustainable livelihoods, escape poverty and protect their wildlife.

The above information about the UK government matching scheme was revised on November 21 to clarify that it only applies to UK residents

Read more about our Seasonal Appeal partner ZSL: ft.com/zsl-facts

Comments