‘Lack of strategy is the strategy’: what Comme des Garçons did next

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In the Marais, there’s a mansion called the Hôtel de Coulanges, formerly occupied by the 17th-century aristocrat Madame de Sévigné, who was best known for her letter-writing. Today, however, it’s rather less romantically dubbed 3537 – the address spans the numbers 35 and 37 on the Rue des Francs-Bourgeois – and it is home not to a literary icon but to a somewhat motley crew of eight designer names. They have strange titles: Vaquera, ERL, Honey Fucking Dijon, RASSVET, Liberal Youth Ministry, Youths in Balaclava (youth is a big thing), Weinsanto and Sky High Farm (a non-profit organisation working in Hudson Valley and New York City, which now has a clothing line to generate additional income). The clothes aren’t easy to categorise. Some of those labels sell sweatshirts and hoodies, leather jackets and jeans; others proffer elaborate and expensive ballgowns in silks and jacquards. The line expletively named after Honey Dijon, a Berlin-based DJ, is elevated merchandise. However, like a 17th-century intellectual salon, those diverse creatives are clustered around the anchorpoint of one powerful woman: Rei Kawakubo.

3537 is the latest spinoff of Kawakubo’s Comme des Garçons, the Japan-born but now globally based fashion brand whose complex empire comprises multifarious offshoots. It includes, of course, the various brands of Comme des Garçons – 17 for men and women, overseen by Kawakubo – alongside the Dover Street Market retail stores present in Japan, China, Singapore, the US, France and the UK. The first opened on the notable London street in 2004; none is based there any more, which is “very Comme”, as many in the fashion industry would say, known as the brand is for its idiosyncratic approach to fashion. The clothes are extreme, often pushing the bounds of wearability (multiple sleeves or no sleeves are a frequent design feature), while a 1998 Comme des Garçons perfume, named Odeur 53, was devised to smell like burning rubber. The stores are designed by Kawakubo and feel anti-luxurious, with raw wood and concrete, while the clothes themselves sometimes feel hidden away. Now situated on Haymarket, the London DSM, as it is abbreviated, has no window displays, with the entrance tucked away on a side street. Unconventional maybe, but the approach has found a passionate and loyal audience: the various DSM businesses account for 30 per cent of Comme des Garçons’ turnover, estimated at around $320m in annual revenue in 2019.

The notoriously media-shy Kawakubo, 78, designs Comme des Garçons, while her partner in life and business, Adrian Joffe, 68, is president of Comme des Garçons and Dover Street Market. In the sun-dappled courtyard of the 3,500sq m 3537 building – which Joffe vaguely asserts “probably will eventually” include a retail space – he’s talking about his passion for young talent, and how that has led to a brand-development division called Dover Street Market Paris (DSMP) to support those eight aforementioned brands. I ask him how he’d define this grouping. “Definitions are by their nature limiting,” he muses.

Joffe is South African, although he’s primarily based between Tokyo and Paris. He is often philosophical in his speech, unlike most of fashion’s business leaders. He is also hands on, present backstage at Comme des Garçons shows, or helping to usher guests to their seats (most presidents and CEOs simply sit front row). In Paris, he works from a bunker-like space under the 3537 building, alongside a group of enthusiastic, cool-looking twenty-somethings. He tells me that 3537 will host exhibitions, concerts, community exchanges, climate-change weekends and collaborations with local schools. He barely mentions retail, but this is akin to the approach of many Dover Street spaces: the company has e-commerce, but the onus is still very much on the physical. “It’s primordial,” Joffe says of bricks-and-mortar retail. He philosophises again. “The social intercourse, the human touch, the vivid real-life experience. Spirit and feeling and love cannot meander, let alone thrive, through a computer. An online shop cannot be the cradle of knowledge, cannot nurture wisdom that discovery and exploration in person could.”

Joffe’s thoughts shift back to DSMP, and to the indefinable nature of the ragtag bunch of designers under its umbrella. “I think we are entering a more and more undefinable world. We may need to invent new terminology. I actually like the real meaning of ‘conglomerate’,” Joffe says. “A thing consisting of a number of different and distinct parts or items that are grouped together... that is what we are. How about an ‘alternative indie radical conglomerate’.” It’s not phrased as a question.

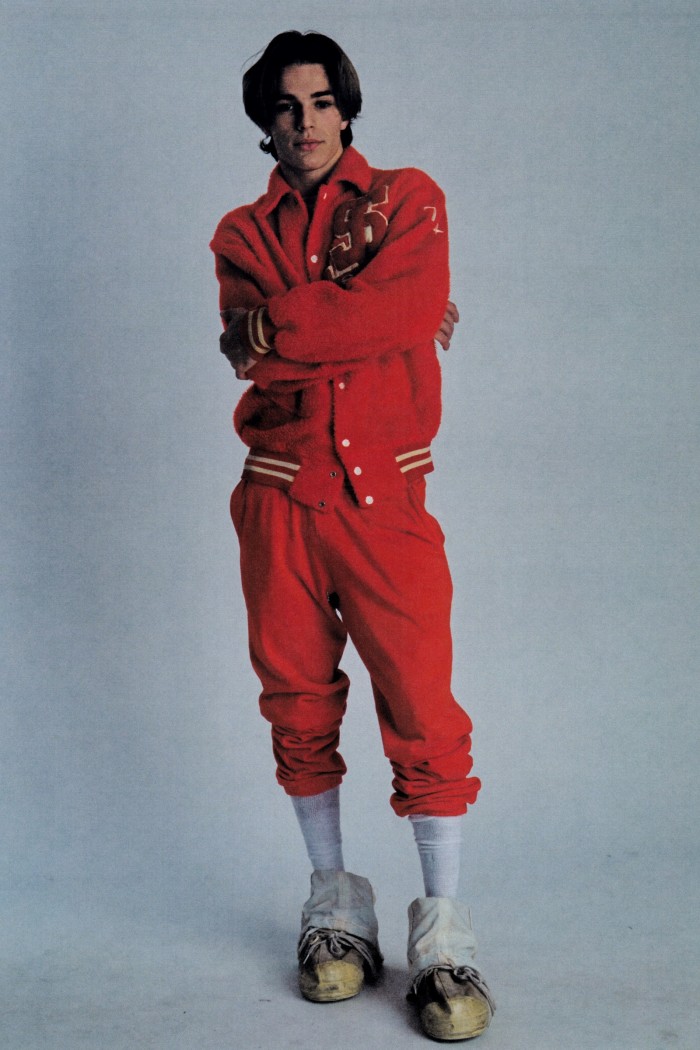

That moniker is a mouthful – Comme des Garçons prefers complexity to simplicity, always. But it’s apt, and it is not only the designers themselves who feel alternative, indie and radical; so too does the structure of the business. Some of the talents were fledgling fashion operations that DSMP began offering support last September through manufacturing, sales and press; others were prompted to create their lines, from scratch, at the encouragement of Joffe and Kawakubo. The designer behind Rassvet, Gosha Rubchinskiy, began as an artist “whose possible logical next step was making clothes”, according to Joffe. Likewise the brand ERL – pronounced as individual initials – designed by Eli Russell Linnetz, a photographer and filmmaker. When he created a video for a Comme des Garçons x Andy Warhol collaborative perfume, Joffe “challenged” him to make clothing for the opening of DSM Los Angeles in 2018. Joffe is something of a design anthropologist: he came across the work of the 11-strong collective Youths in Balaclava (nine men, two women) in Singapore, and found the Guadalajara-based label Liberal Youth Ministry, designed by husband-and-wife team Antonio Zaragoza and Kenia Filippini, via Instagram.

Possibly the most conventional of the brand stories is Vaquera, a New York fashion darling with plenty of press but an unstable business; DSMP began offering support last September. Joffe asserts, importantly, that none of the businesses is “owned” per se by Comme des Garçons – rather that the company helps with brand development, production and distribution. They are sold in the network of DSM stores across the world, but can also sell through other stores, bucking a trend of retailers demanding degrees of exclusivity in terms of stocking brands. 3537 contains a showroom for the designers – this month, they are presenting their s/s 2022 womenswear collections from the space to global buyers. “I think you could say the distinct lack of strategy is a bit of the strategy,” Joffe states. “Having no formula is the formula.”

This approach feels radical, like much of what Kawakubo and Joffe have done. Kawakubo described the retail ideology of the original DSM as “beautiful chaos” when it first opened; in 2013, she said she’d become bored with fashion and started making collections that she described as “not clothes” (she preferred the description “objects for the body”). Very similar to a no-formula formula. It’s one they have been exploring for some time: in 1992, Kawakubo and Joffe established a company with one of Comme des Garçons’ veteran pattern-cutters, Junya Watanabe. That wasn’t usual – then or now. Mostly, if designers have a differing creative vision from their bosses, they strike out alone, or move to work at a different brand. But Kawakubo and Joffe have done it a few times, launching a line of knitwear, dresses and suits by another assistant, Tao Kurihara (her Tao line closed in 2011, but she continues to design for Tricot Comme des Garçons), and in 2012 they launched another headed by Kei Ninomiya, prefixed Noir.

None of those brands could be described as especially commercial, nor easy to wear. Ninomiya’s clothes are like walking topiaries of ruffles, often constructed without stitches; Watanabe enjoys deconstruction, ripping apart and patching together garments like army fatigues and trench coats. They’re both great designers – as is Kawakubo, of course – and there’s an innate confidence in a designer being able to shelve their own ego and support younger talents. It would have been easy to simply label those other designers’ ideas as Comme des Garçons, as many creative directors do with nascent talents in their design studios. But Comme does things differently.

“I think there’s an honesty and humbleness and energy to what Adrian and Rei have created,” says Eli Russell Linnetz from his base in Los Angeles. His label was founded with Comme des Garçons in 2018, and has just launched womenswear. “Adrian has never once told me what to create, and he never wants to discuss business. He just says, ‘Create what you want.’ That’s mind-boggling for someone who’s running a giant fashion empire. There’s a lot of freedom – it feels like a family.” Freedom and family are ideas that come up again and again. The designers of Youths in Balaclava, speaking collectively, state that the connecting thread between the eight DSMP designers is “the attitude of doing things in our own ways, without giving any hoot about it and what people say”. “DSM and CDG represent freedom for me,” says Liberal Youth Ministry’s Antonio Zaragoza. “Both companies question what fashion represents and how they are energised by pure creativity.”

Sadly, those aren’t words or ideas you hear that much in fashion any more, replaced with talk of profit margins and turnovers. Joffe mentions neither of those terms during our conversation: I don’t think he’s ever said the words to me, full stop. His strategy also bucks a tried-and-tested, get-rich-quick scheme of installing new designers into established houses, or even resurrecting long-dead brands. Younger designers – without name recognition – are seen as a riskier investment, for sure. One example, constantly quoted, is Christian Lacroix, launched with a furore in 1987 by Bernard Arnault of LVMH, which never turned a profit in 22 years. “I would never be hired as the person to go and resuscitate an old brand that had lost its way. Too tiring,” Joffe says. “To be part of something new, with the world at one’s feet, is just more exciting and fulfilling to me.” It’s not a community – it’s a Comme-unity. Excuse the pun, but it does mean something.

Comments