Can active fund managers deliver higher returns than ETFs?

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Interested in ETFs?

Visit our ETF Hub for investor news and education, market updates and analysis and easy-to-use tools to help you select the right ETFs.

One of the most important decisions an investor can make is whether to invest with active or passive fund managers, or a combination of the two.

Active fund managers choose their investments in an attempt to beat the index they are benchmarked against, such as the FTSE 100 or S&P 500. Passive funds do not; they are content merely to replicate the overall gains and losses of an index.

The attractions of active investing

Many investment novices conclude that the active route is the obvious one to take. They might assume that they will be in safe hands because fund managers are intelligent people who are supported by a phalanx of analysts. Those experts will be doing the grunt work of examining companies in detail, determining what they are worth and therefore whether they are currently over- or under-valued.

Many fund groups also deploy complex quantitative investment strategies to model financial markets. Others will employ analysts and economists to examine the macroeconomic landscape, providing still more insights that the fund manager can use to help determine what fund managers believe is the “fair value” of equities, bonds and other assets.

Moreover, some managers and analysts meet senior executives of hundreds of companies every year to gather further insights to feed into the decision-making process.

Given all these advantages, surely active funds are likely to beat the index they are benchmarked against?

Pitfalls of the active approach

While an investor who goes down the active fund route may indeed get lucky and make a lot of money, long-term data suggest most of those who trust their money to active managers will end up worse off than if they had invested in passive vehicles such as ETFs.

The underlying truth is that, with a small number of exceptions, the index return is the average return of all investors in that particular market. This means that even as one fund manager beats the index, some other active investor must fall short. In this simplified version of what is known as a “zero-sum” game, every dollar of outperformance must be equalled by a dollar of underperformance.

It is possible for active fund managers as a whole to beat an index but, if they do so, it means some other market participants must systematically underperform.

Can active investors ever win?

Some proponents of active investing claim this is possible. For instance, the foreign exchange market is by definition a zero-sum game because currencies are valued against each other in the form of a ratio. If the dollar has risen against the euro, the euro must have fallen against the dollar.

However, there are plausible arguments that some actors, such as central banks and companies hedging foreign exposures are “non profit maximisers” — ie they are not attempting to make a profit by trading, but are meeting some other policy objective — a tendency that profit-seeking active managers can potentially exploit.

However, in most markets it is harder to identify the potential fall guys. Some observers claim the majority of losers are retail investors who do their own stockpicking and who may be less well informed. But these people account for an ever smaller share of stock market ownership — since 1963 the proportion of UK shares held by individual investors has plummeted from 63 per cent to 13.5 per cent as of 2018, according to the Office for National Statistics.

The effect of higher costs

Even if active fund managers are on the winning side, investors face a further risk when placing their funds with them, because while the average performance of all active investors must, by definition, be that of the index, we are talking in gross terms — that is, before fees and other costs are taken into account.

Fund managers levy an annual management charge and there are other costs on top such as the cost of buying and selling securities and fees paid to auditors and custodians.

Even if these costs are only 1 per cent a year, that drag on performance will soon compound over time.

The result is that passive funds such as ETFs — which tend to charge lower fees and have lower total expense ratios, or costs, than actively managed investment funds — are more likely to deliver higher returns, even though they too will also tend to underperform their benchmark indices in net terms.

Warren Buffett, considered by many as one of the great investment sages of our time, acknowledged this truth when he said in 2014 that his will contained instructions for his wife to invest 90 per cent of the money he leaves her in a low-cost S&P 500 index fund, with the balance in government bonds.

Other factors to consider

As ever, life is messy and some caveats apply. There are some cases where active investors as a whole can outperform (as well as underperform) their benchmark for no reason except that the index is not a good representation of the underlying asset class.

Jan Dehn, head of research at Ashmore Investment Management, points out that only 1.9 per cent of emerging market local currency corporate bonds are included in the sector’s flagship index, while the most widely followed index of EM local currency sovereign debt contains just 13.4 per cent of such instruments. Egregious anomalies of this nature are far less commonplace in the world of equities, however.

And, of course, some active managers do succeed in producing long-term outperformance even when their fees are taken into account. Theory suggests a small number should be able to consistently beat the market purely by chance, but it may be that a small number of individuals are genuinely doing something different that gives them a long-term edge. If so, that edge may not last. Neil Woodford was widely regarded as one of the UK’s star managers for decades, until his flagship fund spectacularly imploded last year.

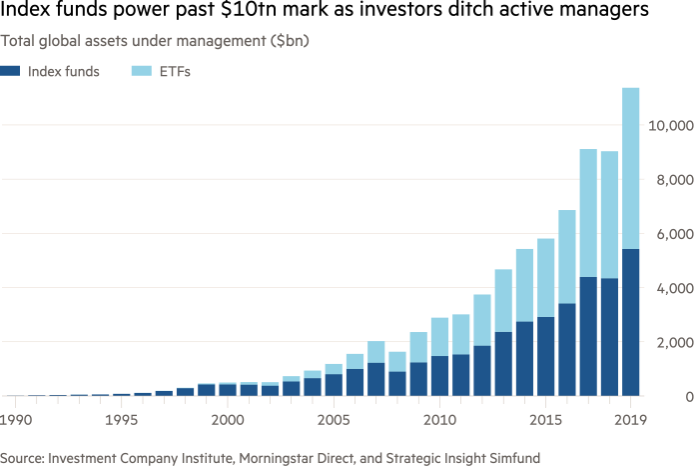

As more investors have come to understand the power of passive investing, the strategy has become wildly popular. The US led this trend and last September Morningstar reported that more passive money ($4.27tn) was now tracking the broad US equity market indices than actively managed money ($4.25tn).

Globally, the volume of assets in index funds has jumped from $2.3tn in 2010 to $10tn, according to Morningstar data.

In the long run, if passive investment continues to expand, it will create problems of its own, in terms of price discovery and capital allocation. That is a story for another day, though.

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

Comments