How to build a better, fairer, greener, safer world for children

Simply sign up to the Science myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

This century is the first when the main threats are induced by one species: humans. Although our ever more powerful technologies can be hugely beneficial, they could, if misapplied, trigger catastrophic setbacks.

However, science, technology and innovation are also essential to solving our most pressing challenges: climate change; global and intergenerational inequity; and the availability of food, nutrition, and healthcare for a growing and ageing population.

Today’s children are likely to see the end of the 21st century. But what their lives, and those of their children, will be like depends on decisions we take today — especially this year, as the UK hosts the G7, a global education summit and the COP26 climate conference.

Our leaders must think about the application of science with the kind of long-term perspective that too often eludes politicians. Young people are campaigning for a better future. Scientists should join them. And politicians should listen rather than continuing to downplay the long-term and the global.

We are facing a raft of newly emergent threats, including climate change, global pandemics and massive cyber attacks. But we fail to prioritise countermeasures because their worst impact stretches beyond the time-horizon of political and investment decisions. I fear we are guaranteed a bumpy ride through this century. Covid-19 must be a wake-up call, reminding us — and our governments — how vulnerable we are.

The world population is forecast to rise to around 9bn by 2050. Food production has kept pace. Famines still occur, but they are due to conflict or maldistribution, not overall scarcity. To feed 9bn in 2050 will require further-improved agriculture, and dietary innovations — such as eating artificial meat rather than real beef.

But it is the geopolitical stresses, the inequalities between and within countries, that are most worrying. Those in poor countries now know what they are missing. And migration is easier. It is a portent for disaffection and instability. Wealthy nations should urgently promote a “mega-Marshall Plan” for Africa — and not just for altruistic reasons.

If humanity’s collective impact on land use and climate pushes too hard, the resultant “ecological shock” could irreversibly impoverish our biosphere. As Harvard ecologist EO Wilson says, “mass extinction is the sin that future generations will least forgive us for”. “Sustainably intensive” agriculture must be a goal.

So the world is getting more crowded — and warmer. In fact, we cannot rule out really catastrophic warming. Climate change is a “global fever”, resembling a slow-motion version of Covid-19. That is why accelerating research and development to achieve carbon-free energy generation, cheap storage and efficient distribution is a global imperative.

The faster these “clean” technologies advance, the sooner they become affordable to low- and middle-income countries where the health of the poor is jeopardised by smoky stoves burning wood.

It is hard to conceive more inspiring goals for young scientists than to ensure sustainable food and energy supplies.

Will the coming “second machine age”, driven by advances in machine learning, create as many jobs as it destroys?

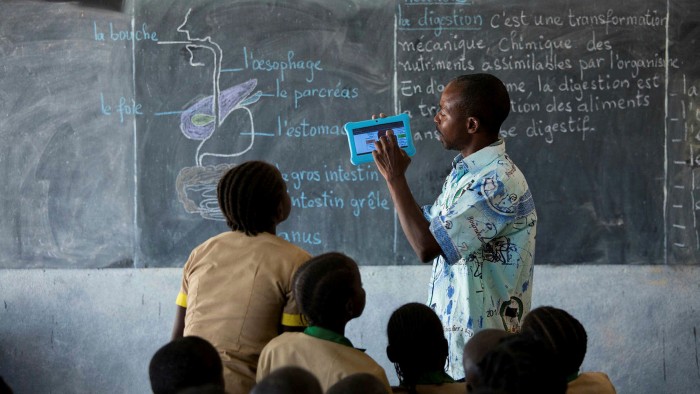

We can be certain that the world of work will change for the next generation. We will need to ensure that they are equipped with the skills they will need for this new world. In this context, a fair society will require massive redistribution to ensure that everyone has at least a living wage. This should be achieved by creating and upgrading public service jobs where the human element is crucial — especially carers for young and old.

In my own special field of space, there is great scope for progress. But coping with climate change is a doddle compared to terraforming Mars. There is no Planet B. We must cherish our Earthly home.

Younger people are more engaged and anxious about long-term and global issues, and their activism gives ground for hope. There is no scientific impediment to a sustainable world. We live under the shadow of new risks but these can be minimised by responsible innovation, and by reprioritising the thrust of the world’s technological effort.

We can be technological optimists. However, the intractable politics engender pessimism. The threats of potential shortages of food, water and natural resources — and transitioning to low carbon energy — cannot be solved by each nation separately. Politicians will not prioritise the global long-term measures needed to benefit people in remote parts of the world decades ahead, and deal with threats to climate and biodiversity, unless their inboxes keep these high on their agenda. Politicians will not prioritise these measures unless there is public clamour from their voters. Scientists must enhance this clamour.

The passengers on “spaceship Earth” are anxious and fractious. Their life-support system is vulnerable. But there is too little horizon-scanning. We need to think globally, rationally, and long term — empowered by 21st century technology but guided by values. We need to do all that now — and 2021’s summit meetings give the UK a unique opportunity.

Global Britain can help mobilise the international community around a new vision that harnesses science, and the energy of the young, to build a safer, sustainable, just and equitable society.

The pandemic reminds us, forcefully, that we are all interconnected, and that science can be harnessed to achieve global goals. We can make the 21st century very different and so much better. Let’s start now!

Lord Martin Rees is the UK’s Astronomer Royal. He is a former president of the Royal Society and Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. He is a co-founder of Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risks.

Read his full essay on the Unicef website, here

Comments