European bond sale order books grow to ‘ridiculous’ levels

Simply sign up to the Sovereign bonds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Investors have been toppling records this year with outsized orders for a rush of new eurozone government debt, but bankers say the true scale of demand for the bonds is becoming harder to discern.

Spain attracted more than €130bn of orders for a 10-year syndication in January, the second record deal in 12 months. In February, an Italian 10-year sale drew €108bn in orders, breaking a record set last summer. Former bailout recipient Greece has also drawn a crowd with new 30-year debt — its first since the financial crisis.

The supersized order books have helped countries’ public debt offices secure more favourable borrowing costs, but have also made what was typically a staid process of “book building” more fickle, and made it harder to judge whether orders really reflect demand for the bonds.

“Back in the day, an order book was viewed as a reasonable gauge of demand,” said Lyn Graham-Taylor, senior rates strategist at Rabobank. The size of order books started to rise in 2017, he said, but “skyrocketed” in 2020 and so far this year, reaching “frankly ridiculous numbers”.

Across the eurozone, the average bid-to-cover ratio for syndications — a standard measure of demand — jumped by around 40 per cent in 2020 compared to the previous year, and has pushed higher this year, according to figures compiled by Rabobank.

Private-sector demand for eurozone government debt is backed by a vast bond-buying programme from the European Central Bank, which is seeking to shore up financial conditions and an economy hobbled by the shock of coronavirus.

Since last March, the central bank’s emergency Covid-19 bond-buying programme has absorbed more than €760bn in public sector debt, buying after it is issued in the secondary market. That leaves investors clamouring for new issues when they need debt for their portfolios.

But some of the apparent interest in these deals from fund managers proves fleeting. In both the Italian and Spanish deals earlier this year, around half the orders fled the book as the government debt agencies sought cheaper borrowing costs. Several bankers said orders from hedge funds are particularly sensitive to price changes, as they may be aiming to resell the bonds quickly at a profit on the open market.

These collapses leave bankers working the phones to reconfirm and then reallocate orders, dragging out the length of the deal. They have also added pressure on the managers of subsequent offerings to understand how buyers will react to new pricing.

“Headline orders suggest issuers can tighten pricing quite a lot, but some of the demand remains very sensitive and will drop if prices tighten,” said Kerr Finlayson, head of the frequent borrowers group at NatWest Markets.

“You can’t just say that because you have a €100bn book that you can set any price you want. You need to balance the high-quality ‘buy-and-hold’ versus the fast money.”

European governments raised an unprecedented €3.6tn in debt in 2020, according to the Association for Financial Markets in Europe. Although auctions remain the dominant tool for government borrowing, syndications allow national treasuries to issue larger chunks of debt and have helped them to meet the financing demands of the Covid-19 response.

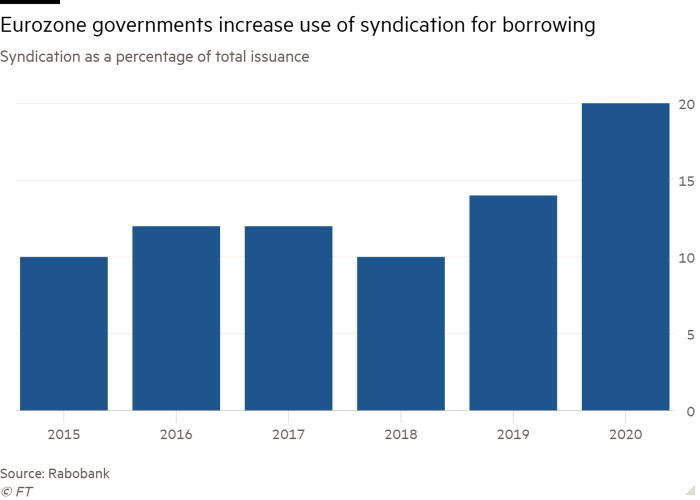

The share of debt issued by syndication climbed last year. Issuance through auctions has meanwhile faced limits from banks’ capacity to act as market makers by holding bonds on their books until they can sell them on to investors.

“Banks’ ability to warehouse bonds has been reduced and therefore it’s more difficult to get bonds in size,” said Graham-Taylor. This has pushed more demand to syndications from investors who want big chunks of debt.

When syndication deals draw more orders than they have bonds to sell, investors are allocated a percentage of the amount they bid for. Some investors have inflated their orders to make sure that they still walk away with the amount they need, bankers and analysts have said.

“This behaviour, which has been observed across government bond syndications internationally, can result in sizeable but potentially misleading order books and therefore should not be taken as an indicator of the level of demand,” the head of the UK’s debt agency Sir Robert Stheeman wrote in a letter to MPs in December.

The UK has also seen big orders for gilt syndications. A 25-year gilt deal in January attracted £60bn in orders, prompting the country to increase the size of the issuance to £6.5bn.

The surge of volatility in bond markets in recent weeks may make investors more cautious about bidding for large orders of bonds. But Jean-Luc Lamarque, global head of syndicate at Crédit Agricole CIB, said he is not anticipating immediate changes in syndication investors’ behaviour. “For the time being, there is still a lot of confidence in the market,” he said.

Comments