Basel — Peace Treaty blues

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Swiss city of Basel is not the most obvious location for a project devoted to art from the Caribbean. Yet it has become home to The Caribbean Art Initiative, which aims to “foster cultural dialogue within, beyond and about the Caribbean region”. In part, Basel has become the initiative’s headquarters because it is also the home of Albertine Kopp, its founder. Kopp previously ran the Davidoff Art Initiative, which had long focused on supporting culture in the Caribbean, especially the Dominican Republic.

When the Davidoff programme closed down in 2018, Kopp felt it would be a shame to waste the knowledge and networks she had built up over the years. Although fundraising is still a big challenge for the future, Kopp and her fellow board members — who include Pablo León de la Barra and András Szánto — have secured the support of the Kulturstiftung Basel H. Geiger (KBH.G), a new art space in the city, for their inaugural exhibition. Entitled One Month After Being Known in That Island, the show underscores that the links between Basel and the Caribbean go much deeper than many of us realise.

Bringing together 11 practitioners from across the Caribbean region, the title is lifted from the Treaty of Basel, which was negotiated in the city in 1795. The accord saw representatives from Prussia, Spain and the nascent French Republic thrash out a peace deal that carved up various Caribbean colonies including Hispaniola, the island in the Greater Antilles which is now divided between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Once colonised by both France and Spain, Hispaniola was, according to the treaty, to become entirely French as the Spanish had relinquished the eastern two-thirds of the island.

“I hadn’t heard of the treaty before!”, exclaims Haitian artist Tessa Mars. One of the artists included in the Basel show, Mars is talking to me from Amsterdam, where she is on a residency at the Rijksakademie. She is a delight to interview, even on Skype, thanks to her effervescent yet gentle personality. Her former lack of awareness of the treaty is hardly surprising. As those distant European leaders attempted at the end of the 18th century to decide the fate of places they neither cared for nor understood, Haiti’s people were making their own history. On January 1 1804, despite the challenges of slavery, civil war and an epidemic of yellow fever, slave-turned-revolutionary Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared Haiti the world’s first free black — led republic and first independent Caribbean state.

That is the narrative with which Mars and her fellow Haitians are familiar. “No matter your level of education and schooling, you get this [history] via your parents,” she tells me. “[Independence] is a fact that cannot be taken away. This happened. You are a being of value.”

Indeed, in the informative catalogue, the curators of the Basel exhibition, Yina Jiménez Suriel and Pablo Guardiola, describe the Basel peace accord as an exercise in “historical futility”. Yet its very hollowness offers fruitful ground for artists accustomed to questioning notions of colonial power.

For Mars, it was a valuable chance to explore territory she was already navigating. Born in 1985, the daughter of acclaimed novelist Kettly Mars, she studied at the University of Rennes in France before returning to Port-au-Prince. There she also worked as a project co-ordinator at Fondation AfricAmérica, which supports contemporary Haitian artists. Working primarily as a painter, her canvases use a bold yet balanced figurative vocabulary to explore notions of collective and individual identity, often touching on what it means to be a black woman both in Haiti and the wider world.

Currently absorbed in texts by contemporary Haitian historian Jean Casimir, Mars says that these days she is asking herself what “it means to live a life of plenitude”. In particular, her focus is on those who are “trying to live in a community and remain in line with [their] heritage and culture . . . who live in rural societies, value their relationship with nature” and prize the “transmission of knowledge from one generation to another”.

Although such communities are ostensibly detached from central systems of power, Mars observes that their residents still find “ways of fighting for [their] rights without taking weapons — [ways] of resisting in daily life.”

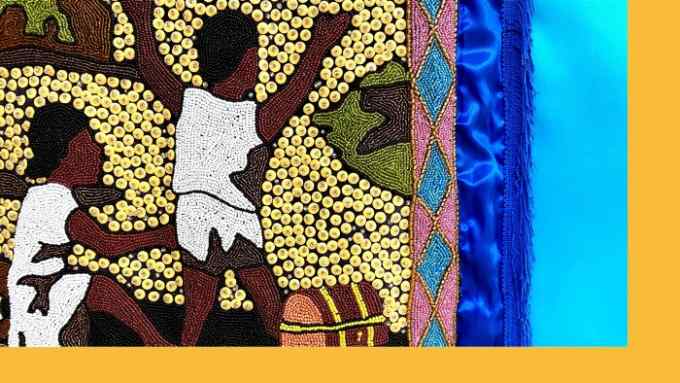

To illustrate this concept of quiet yet committed protest, she has created a new painting for Basel. Entitled “A Vision of Peace, Harmony and Good Intelligence” (a phrase from the peace treaty), it centres on an elderly woman as she crosses a body of water. Around her sprout leafy plants in shades of fuchsia, gold and teal green. Peering through an explosion of sunflower-yellow foliage are human faces while a woman with gleaming azure skin and a red-horned helmet floats serenely in the water in the foreground.

The painting illustrates Mars’s gift — one she shares with a growing number of contemporary artists with links to heritages in the Global South — for weaving her imagery through a magical realist frame.

“For me, magical realism is reality,” she says. In Haiti, where practices such as Vodou still have resonance, such ideas are nothing out of the ordinary. “You feel your ancestors are living with you, guiding your steps, protecting you [and] acting as a source of inspiration,” Mars explains.

The figure of the older woman, then, despite being “a bit stooped” should not be read as a symbol of “suffering”. Rather, she is “going through her life, crossing the water [and] surrounded by things that matter. Her gaze is meditative. She’s meditating on her traversing.”

The horned figure floating in the water, meanwhile, is an iteration of Tessalines, Mars’s fictional alter ego. A feminine reimagining of Dessalines, Tessalines frequently appears in Mars’s works. Her presence acts, Mars has said, to express the voices of Haitian women which have been “silent and unheard” in the public sphere. But it’s also her way of claiming a history in a country where “every Haitian is descended from a hero” but most heroes are still regarded as “male and fighters”.

However, Tessalines has a habit of “taking over” whatever work she enters, laments Mars. In the Basel painting she has thus taken care to place Tessalines and the older woman in such a way as to suggest the pair “work as a unit” as if one is saying to the other “you watch your back and I’ll watch mine”.

That mutual support is essential in Haiti. Due to a history riven with acute poverty, political upheaval and environmental catastrophes, the country is, as Mars puts it, too often viewed by outsiders as “trouble”. But, in truth, she continues, “we have learnt to build our communities and help each other because we have to go on despite things that are beyond our control.”

It’s clear that in terms of exposure to a wider audience, the project should have benefits for the artists involved. But Mars is less certain whether it will impact on the culture of its host city. “I’m wary of the idea of that it will change anything in Basel,” she says. “The whole idea of my work is to concern itself with smaller things.”

Nevertheless, before we say goodbye, Mars is happy to cast doubt on Switzerland’s time-honoured identity as a “neutral” territory. “Of course it benefited from all that was being negotiated in Basel. Look at the chocolate!” she says, alluding to the country’s billion-euro industry. “The cocoa bean is a fruit of colonisation.”

After such a warm-hearted discussion, it is a bittersweet yet acute observation to end on.

’One Month After Being Known in That Island’, to November 15, Kulturstiftung Basel H.Geiger, caribbean.art

Art Days Basel runs September 17-20. Full programme details at kunsttagebasel.ch

Comments