The weird conceptual universe of the artist Laure Prouvost

Simply sign up to the Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Laure Prouvost would like you to imagine that this interview is taking place on horseback. She suggests how I might begin: “ ‘Here we are, doing this article on two horses galloping towards Venice . . . While we were galloping, I asked some questions.’ ”

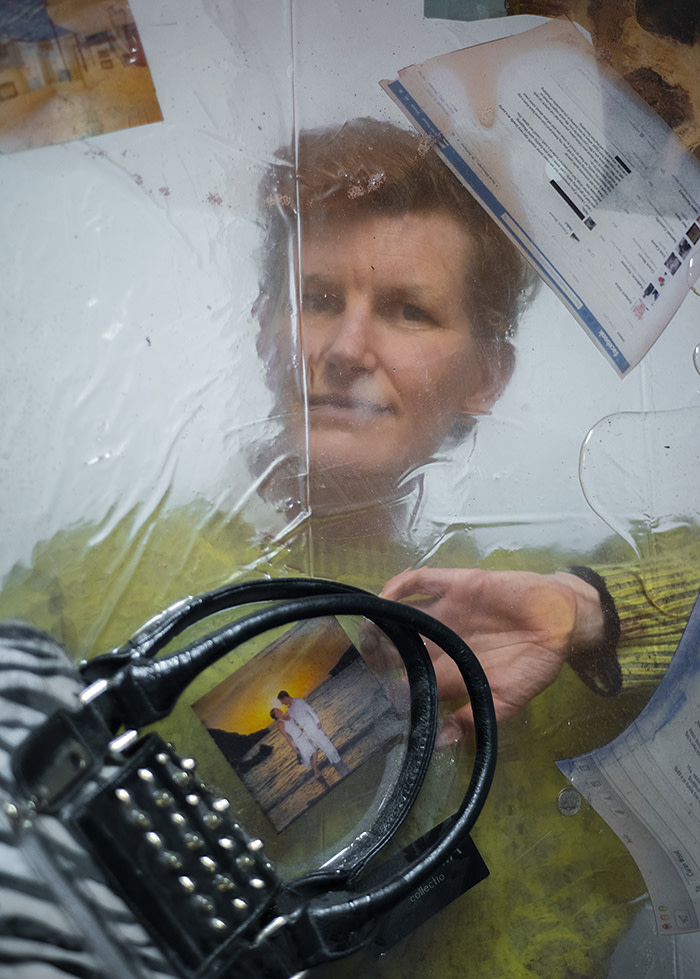

Prouvost is, metaphorically, on her way to Venice; the Turner Prize-winning artist is representing France at the 2019 Biennale, with her project “Deep See Blue Surrounding You”, a video and installation work in which “liquid modernity” is represented through the tentacular body of an octopus. We are, of course, not on horseback but in Antwerp, where Prouvost lives and where she is currently showing Am-Big-You-Us Legsicon — her largest solo exhibition to date — at the nearby Museum of Modern Art (M KHA). The 41-year-old artist has spent the morning posing for theatrical masked photos inside the exhibition space. Now she is perched cross-legged in her studio, dressed in the blousy shirt and black shorts of a Victorian pageboy, and it’s clear that the performance isn’t over.

Few artists flesh out a conceptual universe as full or as tightly sealed as Prouvost’s; fewer still insist on inhabiting it so continuously. Over the last decade-plus she has built up an extensive symbolic vocabulary of “relics” — her word for objects that form part of a larger story — including raspberries, tunnels, bums, tea pots and an imaginary extended family. She ascribes specific meanings to many objects (flamingo means “angry”; nail brush means “excited”) and, to coincide with Am-Big-You-Us Legsicon, has even published a dictionary of her most-used concepts. Does she ever consider widening this vocabulary? “I have been using clementines recently,” she says. “I’m going totally wild.” Her young studio staff — who have so far been pretending not to listen — laugh appreciatively.

Interviews with Prouvost take place inside her semifictional universe. She reacts with dismay to attempts to pin her down on biography, and even dislikes the fact that her career success means that the chronology of her work is now Googleable. “I quite like that it’s a lot of open doors,” she says. Insisting that we’re currently on horseback is a poetic way of showing how language can kick-start the other senses. “Like with my films, often I don’t film the most crazy things I say because it works as strongly as spoken word,” she explains. She believes zealously in the power of suggestion.

Prouvost won the Turner Prize in 2013 for “Wantee”, a work about her fictional grandfather’s disappearance down a tunnel he’s dug under the house. While she continues to vocally mourn his loss (“When you go down the tunnel, you don’t know which way to go,” she tells me ruefully), she keeps her real family out of things. A case in point: when Prouvost got up to accept the Turner Prize, the presenter surprised her by bringing the artist’s two-month-old baby on to the stage. In a slightly awkward interaction, Prouvost declined the suggestion she hold the newborn while giving her acceptance speech. What was going through her head? “Pfff. [It was] the worst idea. I was like, ‘What the f***?’ ” she recalls. “It was a moment where it was about my work.”

Winning the Turner Prize is a career-defining moment for any artist, but for Prouvost it marked a particular turning point; it was the moment in which France claimed her as one of its own. “The press was outrageous in some ways. They were really so proud of it,” says Prouvost, who points out that she’s spent only a minor part of her life in her home country; she lived in Belgium as a teen, then moved to London to study at Central Saint Martins aged 18.

But even with the blessings of la mère patrie (and the licence to deck out her national pavilion in Venice), Prouvost could never be considered a fully French artist. Her art is about being stuck in the “misunderstanding and mistranslating” limbo of thinking in a foreign language, making her the laureate for a global community that speaks English second. “I want to almost [give] power to that pidgin English, which is imperfect,” she says. “You’re floating a little bit, that gives you a lot of freedom.” For the Biennale, she’s made a tapestry of a lettuce with the banner “We will tell you loads of salades on our way to Venice” (“Raconter des salades” means to tell tall tales in French). “I’m just a perroquet, parrot, pirate, pirate,” she muses now, slipping between the two languages playfully.

Prouvost uses humour as entrapment: a way to trick viewers into thinking about her art. From June to December this year, she’ll have a new, and, for the most part, unsuspecting audience to reel in when her first public UK commission, by Art on the Underground, is unveiled. As part of this huge project, Prouvost is putting up posters in all 270 underground stations bearing her sometimes poetic, often pun-driven interpretations of motivational posters: “You are deeper than what you think,” reads one; “Ideally these words would pause everything now,” announces another.

It’s partly this deft linguistic humour that makes her work accessible. And it’s partly the way in which she funnels the personality of an overeager host into it. Prouvost narrates her videos with the tumbling, breathy inflection of a child explaining how to play a game they’ve just invented; even if you don’t quite understand the rules, it’s a pleasure to be included so enthusiastically. For her 2015 exhibition at Haus der Kunst in Munich, her voice whispered apologetically to visitors that if this were her museum the floor would be kissed every night, while at M KHA currently there’s a working tea shop and a bar serving squid vodka inside the exhibition. “It’s hospitality — but of course it’s fictional,” Prouvost reminds me. “It’s pixels, it’s performance, it’s a trigger to engage.”

Because Prouvost is so teasing, she is often described as a great interviewee; journalists, like most people, don’t get much joy from talking to artists whose answers sound like catalogue essays. But she can also be challenging, as skilled in using humour for evasion as for entrapment. I ask what she is most looking forward to about representing France at the Biennale. (After Annette Messager and Sophie Calle, she’s only the third woman to do so.) “Digging a tunnel to the British Pavilion,” she says — a provocative answer, given her own acknowledgment that it’s a “huge issue” in France that she works primarily in English. Asked again, she says she’s looking forward to drinking Campari, then that she can’t wait to see “all these planes f***ing up the planet landing there”. Come on, I say. Be serious. “I’m excited to make a strong piece,” she says with bland finality.

With Prouvost, you have a choice: Engage on her terms, or stay out of her world. She would be delighted if you decided to join her. “The work doesn’t exist without you. If I don’t talk to you, I’m just talking to myself.”

“So are we galloping?” she asks, and claps her hands. “Come on, it would be nice. We can do it if you write it.”

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments