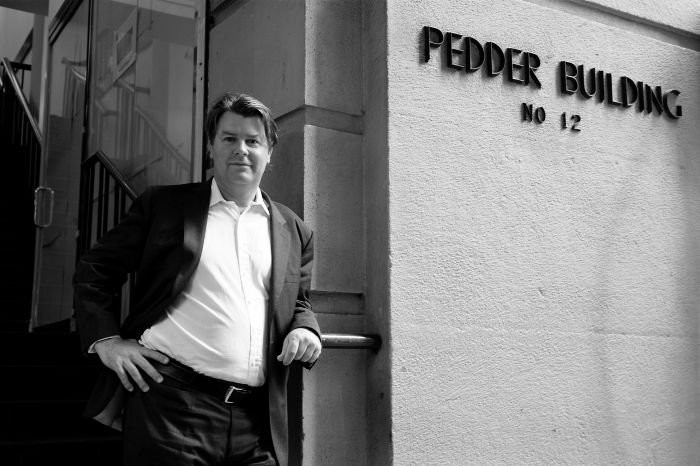

Gallerist Ben Brown on Hong Kong’s art scene

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Ben Brown opened his Hong Kong gallery in the nine-storey neoclassical Pedder Building in Central in 2009, his neighbouring tenants were not quite what an aspirational art crowd might expect. “The building was full of closing-down cashmere shops and fake Louis Vuitton vendors. In truth, it was pretty ghastly,” Brown recalls.

Despite the unorthodox set-up, opportunities quickly sprouted for the Hong Kong-born, London-based dealer. Among Brown’s first clients was a Hong Kong collector who was buying a wedding gift in a shop next door when he happened to hear that Brown was selling a “very small but very lovely” Pablo Picasso drawing for less than $100,000. “It was his first Picasso; he’s since bought around 10 pieces from me,” Brown says.

It was a fortuitous sign — back then, “nobody was showing great western art”, Brown explains. Most collectors either bought traditional Chinese art — scroll paintings, ceramics and jade — or contemporary Chinese art, which was undergoing a speculatively fuelled, shortlived boom at the time.

Determined to create a gallery cluster, Brown set out to enrol other dealers in Pedder Building, including Lisson Gallery’s Nicholas Logsdail. “He was impressed by the space but he ended up going to New York instead,” Brown rues. Lisson is finally taking the plunge in China, opening a space in Shanghai this month.

Pedder’s gallery credentials were cemented in 2011 when Gagosian moved in. It was the year China rocketed to the top spot in the global art market, with Asia’s mushrooming billionaire club a lure for western art dealers. “We wanted to be in a hub city in Asia where we could reach collectors across the continent,” says Gagosian’s managing director Nick Simunovic, adding that Hong Kong’s business-friendly, tax-free status was a huge incentive.

The next few years represented a seismic shift in attitudes towards international modern and contemporary art, which brought western dealers flocking to Hong Kong. Six top-flight galleries, including Lehmann Maupin and Simon Lee, now occupy Pedder, while in 2018 the nearby H Queen’s gallery building officially opened, with David Zwirner, Pace and Hauser & Wirth among its high-profile tenants.

It was conceived as a commercial building but designed by the Hong Kong architect and collector William Lim with art exhibitions in mind. I ask if Brown was ever tempted to relocate to the more high-tech H Queen’s. “Absolutely! I went to have a look,” he shoots back. “Both buildings have their pros and cons: location, price, ceiling height, easy access, management, etc. But the fact that nobody has moved says a lot.”

Other cultural districts to crop up in recent years include Wong Chuk Hang on Hong Kong’s beachy Southside, where rents are a snip of those in eye-wateringly pricey Central, and, currently under way, the £2.6bn, 70-acre cultural district called Victoria Dockside, masterminded by the Hong Kong developer and collector Adrian Cheng.

If there is one event universally credited with putting Hong Kong on the international art map, it is Art Basel Hong Kong, which replaced Art HK in 2013. The Hong Kong-born collector Patrick Sun is among those full of praise for the art fair. “Art Basel’s arrival was pivotal. The contemporary art scene really picked up afterwards,” says Sun, who started out buying traditional Chinese painting but switched his focus to “gay Asian contemporary art” around five years ago.

“But if you go back to before Art Basel, Ben Brown was one of the early believers in Hong Kong. He was one of the visionaries who kick-started things.”

At this year’s fair, Brown is showing six semi-abstract landscapes by his mother, painted in the 1980s. Describing them as “not particularly valuable but rather good”, Brown has modestly priced the works at HK$120,000 (US$15,280) each.

An accomplished painter, Rosamond Brown moved to Hong Kong in the mid-1960s when she was just 26. She soon ingratiated herself into the art scene, ordering acrylic paint for fellow artists Hon Chi-fun, Gaylord Chan and Cheung Yee in exchange for tutorials in how to use a Chinese brush.

The impetus for Brown to show his mother’s work came from Adeline Ooi, the director of Art Basel Hong Kong, who told the dealer the fair needed more Hong Kong women artists, a sentiment he fully supports.

The Brown family are also behind one of Hong Kong’s only museum acquisition funds, which provides a modest but regular budget for M+ to buy works at the fair. The HK$5m 10-year fund, modelled on a mixture of the Tate’s Outset fund and the Turner Prize, will run until 2024. In 2012, meanwhile, the former Swiss ambassador to China, Uli Sigg, donated his $163m art collection to M+.

In a country where philanthropy is not high on the agenda (there are few tax breaks for Chinese collectors), Brown feels a sense of civic duty to fill some of the gap. “Quite frankly, [art] has helped us make money, so we should give some back,” he reasons.

Hong Kong’s museum scene as a whole has been woefully lacking, but here too the tide is turning. The Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts opened last May, while the Hong Kong Museum of Art is currently undergoing a HK$930m renovation. Most hotly anticipated, however, is M+, the crown jewel of the West Kowloon Cultural District, which is due to launch in 2020 after repeated delays.

Brown believes M+ will bring balance to Hong Kong’s reputation for being hyper-commercial. “Currently, if you want to go and see great art, you go to someone who has a vested interest in selling you something. Hong Kong is lacking an unbiased eye, an institution that will tell you ‘this is great art’ without placing a monetary value on it. That’s what M+ will rectify,” he says.

The museum’s opening will cap a decade of rapid growth in the Chinese art market, but the next 10 years appear less bullish, according to a new report released by Tefaf art fair earlier this month. Reinforcing current trends, the report suggests that western dealers will continue to expand their piece of the pie, but at the expense of Chinese galleries and artists.

Brown is optimistic that there is plenty to go round, despite a slowing Chinese economy. “China will have its ups and downs, but I predict that the upper middle classes, as well as [those] in Indonesia and the Philippines, will get richer,” he says. “New people will begin to buy art and they will get used to the fact that it is not a pure investment.”

That said, Brown makes no bones about the fact he is in Hong Kong to make money. “If that stops and I can’t do anything about it, then I will shut down. But at the moment I am very happy.”

Art Basel Hong Kong, March 29-31

This article has been amended to reflect the fact that the Pablo Picasso drawing was sold for less than $100,000, not less than HK$100,000

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments