Munich jewellery exhibition comes into its own

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Argentine jeweller Alejandra Fabiana Agusti sent two of her pieces to Munich to be shown at Schmuck, the prestigious annual exhibition of the world’s best contemporary art jewellery, she was thrilled to become one of only 66 people selected from more than 600 applicants.

But German customs officials were less than impressed and refused to let one of her necklaces into the country — because it was made from bullet casings. Called ‘Memory’, it was an item of jewellery with a strong social and political message that, says Agusti, pays “homage to the women in my life and in my past . . . who fought for us to be where we are today”.

It was a moment when contemporary jewellery came up against political reality — which is very much where many of its practitioners want to be. Whether through playfulness, a desire to shock, the use of unusual materials, or unexpected subject matter, this year’s Schmuck showcased a group of jewellers demonstrating all the ambition and intensity you would expect to find among any group of contemporary artists.

Established in 1959, Schmuck (which is German for jewellery) has taken place in March every year since 1962, except when it was disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic. It is part of an international craft trades fair held at a vast exhibition hall on the outskirts of the city.

Tucked away at the back of the hall — past displays of handbags and nativity figures, a sauna seller and hulking handmade boats — this year’s Schmuck sat alongside booths for some of Europe’s best art jewellery galleries, including Marzee from the Netherlands and Platina from Sweden.

One of the show’s supporters is the Chamber of Trades and Crafts for Munich and Upper Bavaria. Wolfgang Lösche, head of its department for trade fairs and exhibitions, stresses “how important Germany has become . . . in the field of jewellery . . . The entire city of Munich has profited from [Schmuck]”.

Each year, Schmuck’s organisers invite a highly regarded industry insider to curate the show. This year’s choice was Caroline Broadhead who, for nearly a decade, was jewellery and textiles programme director and BA Jewellery Design course leader at Central Saint Martins art college in London. She is now professor emerita, having retired in 2018.

Broadhead was pleased with this year’s wide selection of international practitioners — jewellers from 23 countries submitted work for consideration — and says her criteria for inclusion were “very open”.

Among those who made the cut were well-established contemporary jewellers such as Christoph Ziegler. He showed two contrasting pieces: a glass ampoule pendant, ‘Ampoule’, and, in contrast to its manufactured fragility, a grounded, organic necklace made from olive wood and rubber cord, called ‘Memories II’.

Also included was Dutch jeweller Bas Bouman, whose chain-link necklace had a touching story, which he said “fits in the tradition of ethnic jewellery”. The piece was made of the chicken bones that were in the soup his mother made every Saturday for the whole family, and continued to make for his father until his recent death. It was made as a tribute to his parents, as well as to the animal that supplied the bones.

Broadhead was particularly proud of the work by CSM alumna Veronika Fabian, a Hungarian jeweller based in London. The pieces were a technical tour de force that consisted of large metal chains created from smaller ones, some embellished with oversized hallmarks.

Argentine jeweller Jimena Rios — who describes her work as a “conversation between contemporary and devotional and traditional jewellery” — exhibited a bracelet, ‘Self Portrait with Corals’, featuring a hand that was made from what looked like linen, embellished with silver, gold, coral and glass beads. “These pieces have the weight of touching and grasping and holding and comforting,” she says.

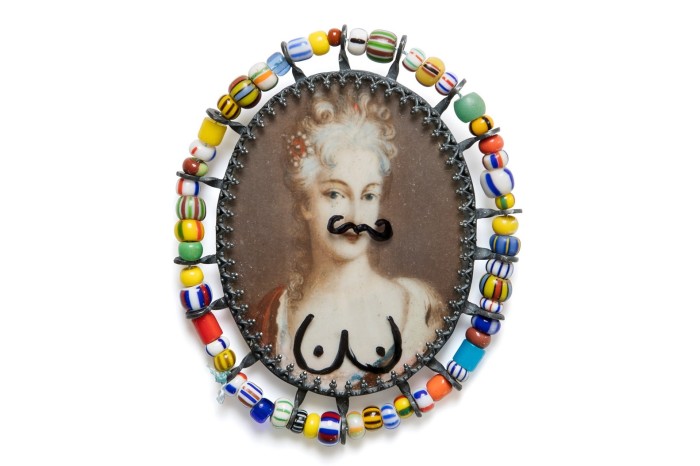

Broadhead’s exhibitors used an eclectic array of materials. There was a necklace of beads made from oil shale from Dorset’s Jurassic coast by UK jeweller Sarah Powell; a talisman-like carved driftwood pendant, complete with jade tongue, from New Zealander Neke Moa; a silver and diamonds ‘Barbie’ shoe by Maria Militsi, a Greek jeweller based in London; and a ‘Colonial Comeuppance’ brooch by South African Geraldine Fenn, whose centrepiece was a naughtily graffitied portrait miniature.

For sheer silliness with a heartfelt message, there was also the ‘Olden Language Badge’ by Timothy Information Limited, which consisted of a booklet called Esperanto for Beginners pierced by a blue metal peg.

Away from the exhibition itself, Schmuck has given rise to numerous shows and events in the heart of Munich, called Munich Jewellery Week. More than 50 venues, including shops and industrial spaces, are taken over by jewellery designers and galleries from around the world, and the city’s Design Museum is also involved.

If there was a shadow over this year’s event, it was that some experts worried whether enough new collectors and gallerists were coming through. But, for now, it remains a key calendar fixture for anyone interested in the space where art meets jewellery.

Comments