Drug pollution in rivers raises risks of antibiotic resistance

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

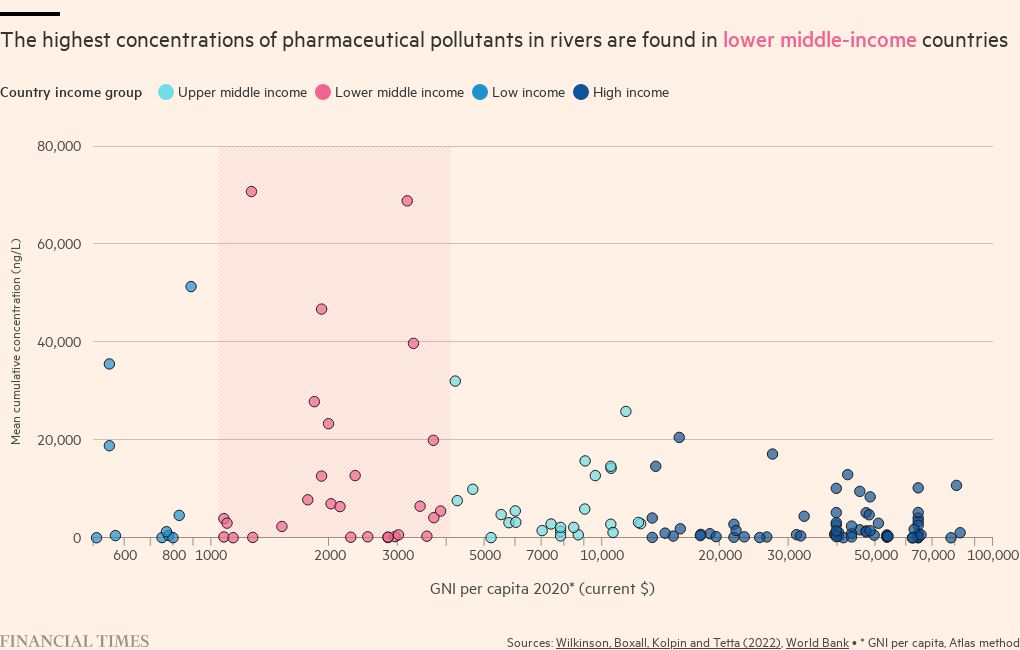

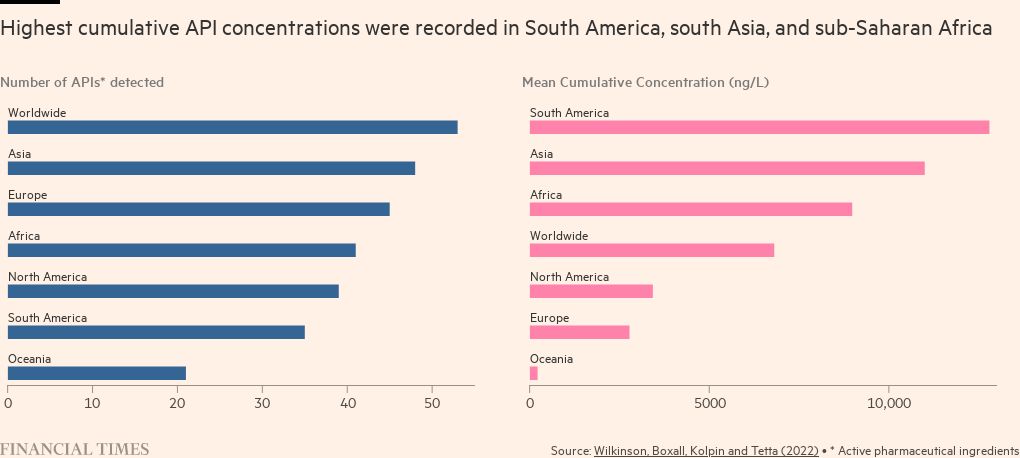

Lower middle income countries in South Asia and Latin America have some of the world’s highest levels of pharmaceutical pollutants in their rivers, raising concerns over the risk of bacteria developing resistance to antibiotics.

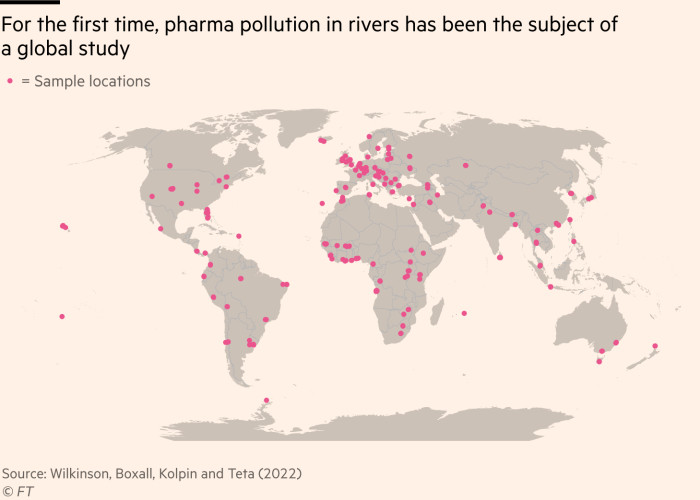

A pioneering analysis based on samples in 104 countries published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has found that “contaminants in surface water pose a threat to environmental and/or human health in more than a quarter of the studied locations”.

It throws a spotlight on regions where poor management of waste and wastewater is combined with local pharmaceutical production — and where greater healthcare spending by individuals, or governments, has improved access to medicines.

The presence of contaminants signals high usage of medicines and can cause the development of microbes that are drug-resistant in the water system. Bacteria in rivers that become drug-resistant could then infect fish and enter the supply of drinking water for humans and animals.

Concentrations of ciprofloxacin, one of 13 antibiotics identified, exceeded safe limits at 64 of the sites examined. The highest levels, at Barisal in Bangladesh, were more than 300 times the limit. The highest concentration of drugs overall was recorded in Lahore, followed by La Paz and Addis Ababa.

These findings highlighted important drivers behind the growing “silent pandemic” of antimicrobial resistance, which was recently estimated to be responsible for at least 1mn deaths each year globally.

They also look set to spark a fresh debate about the need for strengthened global surveillance to identify the extent of inappropriate drug use — and the locations contributing most to resistance.

David Heymann, epidemiology professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said there was a need for broader monitoring of drugs in water supplies, in addition to the existing networks developed for specific diseases. Such surveillance “has been very effective for polio and is being done for cholera . . . it should be expanded,” he argued.

The PNAS study was the most comprehensive undertaken to date, and built on previous research that was limited to richer countries. It involved 127 academics and used a standardised test to measure levels of 61 “active pharmaceutical ingredients” in water at 1,052 sites along 258 rivers, in countries where 471mn people live.

It identified high concentrations at sampling sites close to pharmaceutical manufacturing plants, including in Barisal and Lagos, raising concerns over the need for tougher controls on waste emissions from companies producing drugs.

It also found high concentrations in places with a high discharge of sewage into rivers — such as in Tunis, Tunisia and Nablus, Palestine — and those with significant waste dumping, such as Nairobi, Kenya and Accra, Ghana.

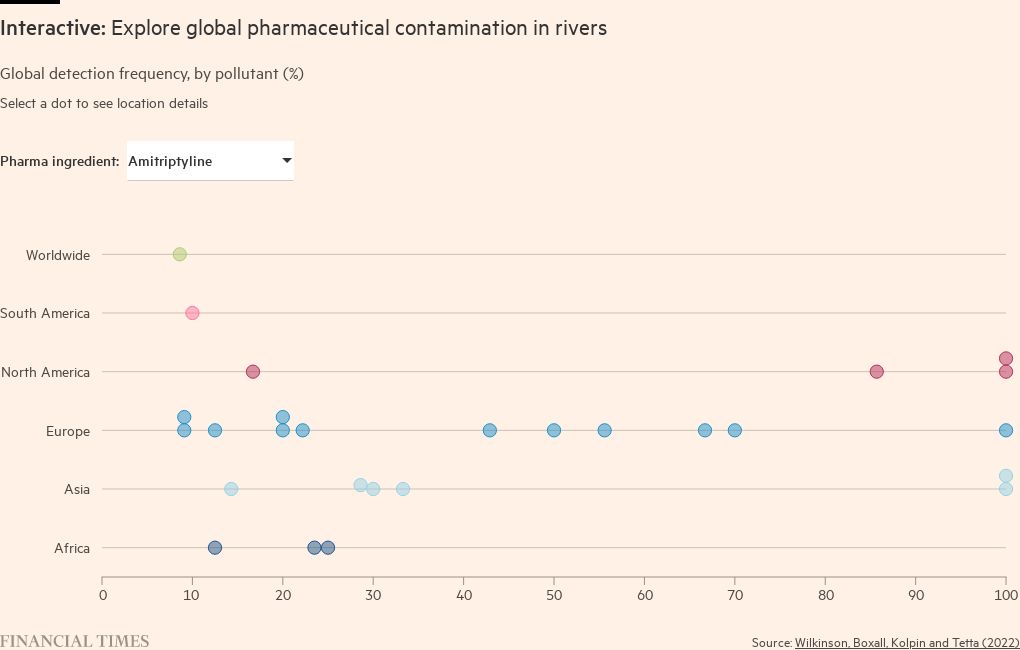

The authors of the analysis highlighted how, in areas where medicines are less regulated and drugs can usually be obtained without a prescription, there was wide variation in the levels of antibiotics in rivers. Those included parts of Africa, which they suggested partly reflected a lack of regulatory oversight of the use of medicines in humans and animals.

Tim Walsh, microbiology professor at Oxford university, said the study highlighted the need to clamp down on overuse of antibiotics by pharmacies, but also stressed that pharmaceutical concentrations in rivers were partly the result of their use in agriculture and hospital waste.

While there has been a growing focus on providing new financial incentives to stimulate the thin pipeline of new antibiotics in development by drug companies, there has been less attention on supporting the appropriate use of antibiotics — including in lower and middle income countries.

Experts have called for a combination of broader funding, appropriate stewardship and pooled procurement mechanisms to pay for widespread use of the right medicines with appropriate safeguards.

Comments