Investors map out ways to win tax breaks in deprived US areas

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

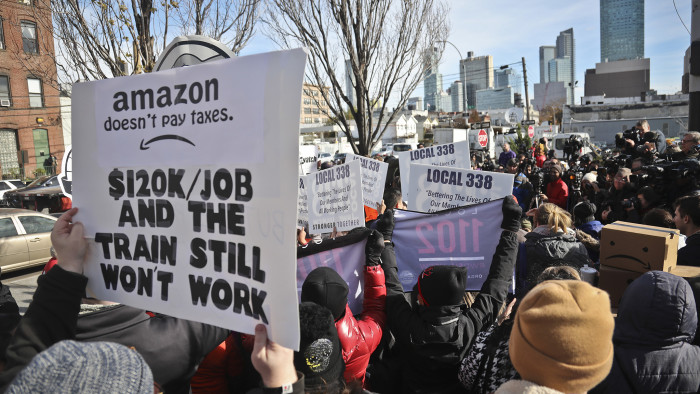

When community activists, unions and local politicians thwarted Amazon’s plans for a corporate complex in Queens, New York, the victory rattled investors and financial advisers who hope to profit from the federal government’s Opportunity Zones programme. Before withdrawing, Amazon said it would not apply for generous tax breaks allowed under the scheme. But outside developers and any of Amazon’s partners investing in the neighbourhood could have done so.

Under a law passed in 2017, the US Treasury has designated more than 8,700 areas across 50 states as economically distressed, labelling them “opportunity zones”.

The legislation aims to induce investors to consider developments in deprived neighbourhoods in return for tax relief on capital gains. Steven Mnuchin, US Treasury secretary, has predicted the measure could attract up to $100bn into these zones.

Areas qualifying for this relief include blocks in the borough of Queens, such as the one Amazon picked last November as the site of a corporate campus, only to cancel its plans three months later.

Amazon’s U-turn showed that local people in poorer communities would not automatically welcome outside investors seeking tax benefits.

Anna Snider, head of due diligence for the chief investment office at Bank of America Global Wealth and Investment Management, says the fight gave many considering such investment pause. “It made them stop and think.”

Even before the Amazon withdrawal, some advisers had expressed reservations about backing schemes when much of the detail of the programme still has to be fixed by the US Treasury. “We were telling our clients to hold off, there was too much confusion,” says Jeff LeClair, an FT 400 listed adviser with Wells Fargo Advisors in McLean, Virginia, recalling his attitude to the scheme last year.

In principle, investing in opportunity zones will offer large tax savings. If investors hold on to relevant assets for 10 years, they will pay no tax on capital gains they realise from those investments. Congress has set no limits on those tax benefits and the regulations the Treasury has proposed so far attach fewer strings to investors’ eligibility when compared with similar schemes aimed at spurring investment in neglected areas.

Generous tax relief and minimal red tape have encouraged investors, financial advisers, asset managers, and broker-dealers to scour zone maps that the Treasury released in June 2018 for investment opportunities. Selection of the zones was based on “stale data” from the 2010 US census, so some designated tracts include locations that “have benefited from economic growth for the past 10 years”, according to Nicholas Millikan of the CAIS Group, whose company markets opportunity zone investments.

Some zones are located in stubbornly rundown districts. Yet one designated area in New York City is separated by only a five-minute walk from the popular Guggenheim museum and upmarket Manhattan residences.

Investors hoping to exploit opportunity zone tax breaks can engage in “zip code arbitrage”, says Mr Millikan, who favours funds investing in Stamford, Connecticut and Newark, New Jersey as well as in New York City. “The opportunities are not uniform,” says Mr LeClair.

The scheme’s distressed areas are home to 11 per cent of the US population, or 35m people, and suffer higher average unemployment rates than the rest of the country — 13 per cent compared to an average of about 4 per cent, according to a UBS report in January.

Despite the Treasury’s delays in setting out how the programme’s detailed rules will apply, Mr LeClair and other advisers have begun helping investors evaluate buying stakes in zones. Many stress the need to apply a precautionary approach. For example, investors need to withstand 10 years of being unable to access the cash they invest. “Illiquidity is a primary concern,” says Andrew Lee of UBS Global Wealth Management in New York.

“I wouldn’t use this for the novice investor,” says Ira Walker, an adviser with UBS in Red Bank, New Jersey. “It is a very sophisticated vehicle.”

UBS, for example, is offering clients investment schemes in opportunity zones that require commitments of $250,000 or more.

The best candidates for exploiting the scheme are investors previously planning to purchase assets in designated tracts who can already anticipate an appealing return without the expected additional tax savings, financial advisers say.

For Mr Walker’s clients, this has “worked out wonderfully”, he says.

Investors must commit funds by the end of this year to take full advantage of the scheme’s tax break. But some advisers are encouraging clients to resist the throngs of asset managers hawking opportunity zone funds by emphasising the curtailment of tax benefits from the year’s end.

In March, Treasury officials sent a second set of detailed proposed regulations for the scheme to the White House, which has yet to be approved.

Although delays have stalled some investors, that should change later this year when all the regulations are expected to be finalised. “I think this could become a significant part of the business for us,” says Ms Snider, who resides in a Harlem neighbourhood not far from an opportunity zone. But she adds the best opportunity zone investment strategies are “going to require some learning”.

Comments