If you want to know why people are reluctant to be leaders, ask them

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is a reader in leadership at the Bayes Business School (formerly Cass)

When senior leaders are looking for talented staff to promote into management, they often assume that employees will fit around what the company wants. That’s an outdated attitude.

In your annual staff survey, have you ever seen the question: “What would motivate you to become a leader or manager, and what do you think are the disincentives?” I would guess not. But as many well-qualified professionals, especially women, avoid becoming line managers, companies need to fit more around their employees.

Take the case of medicine. In 2019, the Organization of Danish Medical Societies was worried that the country’s government assumed doctors were reluctant leaders. But was that true? They approached me to find out. We asked the doctors about possible incentives and disincentives of going into management.

We learnt a lot. The overwhelming majority of Danish doctors said they would be happy to take a leadership role. But their key motivation in doing so was to have a “positive impact on the team, department or organisation”. They also wanted leadership training.

The disincentives included fears about extra administration, longer hours, burnout, lack of resources and change-resistant organisational cultures. From our 3,500 survey responses, we prepared recommendations on how to improve succession by adapting health systems to reflect the motivations of potential medical leaders.

More broadly, it is worth remembering two things. First, evidence suggests that a boss’s competence is the greatest influence on employees’ job satisfaction — and it predicts individual performance and retention.

Second, workplaces need a diverse range of experts. If we do not see anyone like us in charge, we are unlikely to enter the leadership pipeline.

And if you do not have diversity in the middle, you will never have it at the top. A new UK study by Nikolaos Theodoropoulos, John Forth and Alex Bryson found that the gender pay gap closes when the share of female managers in the workplace rises. This is because women’s wages are more likely to go up under a female boss, while men’s decline.

Interestingly, the authors reveal that this is “more pronounced when employees are paid for performance”. As such, they note, women are more likely to enjoy equal pay when female managers can choose how to reward performance.

It really does matter who our line managers are.

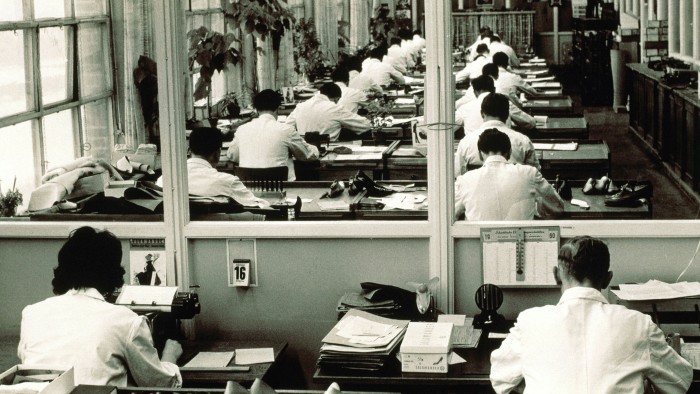

Companies traditionally handpicked and nurtured future leaders, sometimes over 10 to 15 years. But the long view was shortened when technology accelerated innovation, the labour market went global, and companies became less secure about their future. This required what Peter Cappelli, a Wharton business school management professor, and his co-authors call “agile human resources”.

New FT Live event

FT’s Future of Work event series is back this October. Join Facebook, LinkedIn, AstraZeneca, Nasa, and more as they explore key themes such as omnichannel workplaces, the impact of AI on jobs, privacy and security issues in distributed workforces. To book tickets, visit here

In this environment, external hires often competed with internals for management positions. Companies focused less on progressing the “company man”, and encouraged employees to take responsibility for their own career development.

The problem was that this created a superficial democratisation of leadership — “take a training course and you too can become a leader”. Like nettles in spring, leadership training companies were everywhere. Billions were spent on their programmes.

We should expect individuals to take an interest in their career, of course. But those who signed up to be leaders were more likely to be confident, white and often male.

There are other ways to diversify a talent pipeline. In 2013, the then director-general of the BBC, Tony Hall, announced that women would present half of all breakfast shows on local radio by the end of the following year. Half of that workforce was already female, but only 25 per cent of them got any time on air.

Natasha Maw, a former radio producer who had run mentoring schemes, helped to implement the changes. “I knew the talent was already in local radio, often working on overnight ‘graveyard slots’ or as ‘traffic girls’, so I advised against a recruitment drive,” she says. “We developed an existing pool of female reporters and presenters, who were sponsored by well-known names.”

The initiative was a success and the quota was met. This year, the BBC launched its most ambitious strategy yet, which includes developing and nurturing diverse talent into leadership positions. This is a pointer to the future.

There are two lessons here. One is that organisations need to find out what their employees want, rather than making them fit around corporate strategy. The other is to train and nurture diverse leadership talent from within. It is easy for firms to find out how to do it. They only need to ask.

Andrew Hill returns next week

Letter in response to this article:

Don’t conflate leadership with management / From Kati Vilkki, Lead Coach, Reaktor, Helsinki, Finland

Comments