Advisers test new fee models to widen their customer base

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Giving counsel on which assets to buy was once the central pillar of what registered investment advisers offered clients, but in recent years their role has sprawled to include financial planning, tax advice and other services.

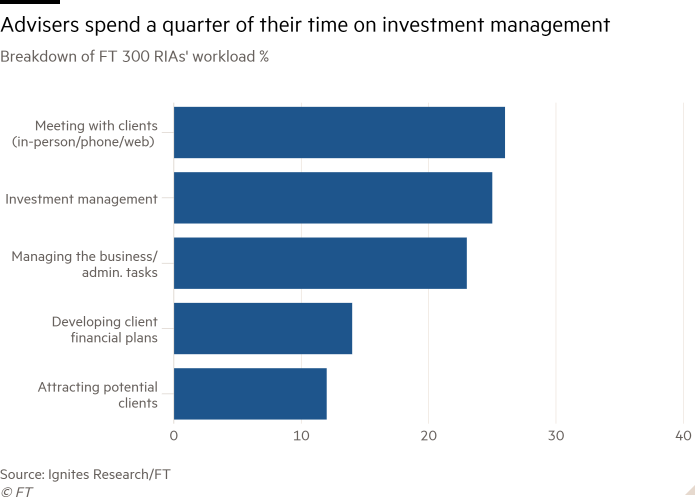

Investing now takes up just 25 per cent of their time, according to this year’s FT 300 top registered investment advisers. Yet the vast majority still use the decades-old approach of charging clients based on their assets under management — leading some industry observers to question whether this represents good value for clients.

“The AUM model is prevalent because it’s easy to explain, and regulators accept it,” says David Canter, head of RIA and family offices at Fidelity Institutional, which provides an array of services for advisers. The recurring revenue also suits advisers, he adds.

Yet not all advisers and clients are happy about the dominance of the AUM fee. A common criticism is that the rising financial markets of recent years have enlarged clients’ accounts, meaning they have to pay their advisers higher fees regardless of the amount of work those advisers are putting in.

“It doesn’t take more time to buy 1,000 shares of stock versus 100 shares of stock, so why should the adviser get paid more for the account that needs 1,000 shares?,” says Randy Waesche, chief executive at Resource Management, based in Metairie, Louisiana. “More clients are going to be asking what sort of value they’re getting for the dollars they’re spending.”

His firm is part of a small but growing segment of the market that does not adhere solely to AUM-based charges. Resource, for instance, charges clients separately for services outside of investment management, based on a combination of hours worked and the complexity of the tasks.

Wealth management company Charles Schwab, meanwhile, adopted a subscription advice model last year: clients can receive unlimited advice from a financial planner for a one-time fee of $300 and an ongoing charge of $30 per month.

Hourly fees, flat fees and similar arrangements rarely generate the same revenue as asset-based fees, however. Where advisers do use them, some will provide a more basic service to compensate for lower revenues, while others offer these structures to attract younger investors with fewer assets.

The proportion of FT 300 advisers charging a combination of AUM-based fees and flat fees rose from 26 per cent in 2018 to 28 per cent in 2019.

Buckingham Strategic Wealth, based in Clayton, Missouri, takes the vast majority of its revenue from AUM fees, but it uses flat fees for specific projects such as financial planning. “The AUM model is still primarily our model of choice, but we’re in the service business and so we have to be flexible,” says its president Wendy Hartman.

Asset-based charges typically decline as accounts get bigger. That means, for example, a $1m account might be charged 100 basis points a year while a $10m account might be charged 70 to 80 basis points.

Even so, among FT 300 advisers, the average AUM fee has held steady at 73 basis points for the past three years — which can look odd when other parts of the asset management ecosystem have seen dramatic fee reductions.

Last year, for example, discount brokerages such as Charles Schwab and Fidelity, which had charged roughly $5 to $9 per trade, cut those commissions to zero. Meanwhile, the battle between passive and active management styles over the past decade has brought down costs significantly for managed funds.

Rather than cut fees, many RIAs are competing by increasing the services they provide but for the same cost — in effect a form of fee compression.

For clients of The Colony Group in Boston, the AUM fee includes connections to college admissions consultants for students and travel concierges. The adviser will also charge hourly for additional services such as bookkeeping. “We are constantly under pressure to offer value for what we do,” says Michael Nathanson, chairman and chief executive.

Yet Michael Kitces, publisher of financial planning industry blog Nerd's Eye View, argues that the real weakness of asset-based fees is that they limit advisers to only take clients with enough assets to make it economical. “The AUM model works well for those it serves. But it limits the market,” he says.

An investor with $100,000 might generate only $1,000 a year in fees, so would be turned away by many RIAs. Among the FT 300, 61 per cent of advisers set an account minimum of $500,000 or more.

Mr Kitces has also co-founded a membership organisation of advisers offering subscription-based fees. He sees this pricing model as an opportunity to serve clients who have fewer assets but who still need advice. “It can make advice more affordable,” he says — while opening up the market to millions more investors and deepening the client pool for advisers.

For now, at least, most advisers expect AUM fees to continue to be the standard. But both client and adviser should benefit from the latter’s greater willingness to experiment with how they charge.

Loren Fox is director of research at Ignites Research.

Comments