Is the pandemic an economic cul-de-sac?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. The Fed minutes were dull, so I ignored them. If you disagree (with that or anything else) email me: robert.armstrong@ft.com

A new new normal, or the old new normal?

Christopher Smart, a chief strategist at Barings, thought that I made too big a deal of the recent deceleration in the economic data. He thinks investors have moved on. He emailed:

We know the data is slowing, because it could not possibly continue to accelerate . . . investors are intensively focused on next year and the year after. Where will growth and inflation settle if and when Covid variants dissipate and policy support fades away? Much of this will be a new round of the ‘secular stagnation’ debate. Are we still headed lower on growth and rates, as we have been for the last 40 years, or is there something new about fiscal and monetary policy that can generate 2 per cent inflation again? Whoever gets that right will be retiring early.

I will not be retiring early. I suppose I could bet my portfolio, such as it is, one way or the other — using leveraged Treasuries, or cyclical stocks, say. But it would just be a guess. Determining whether we are entering a new regime or returning to the old one is above my pay grade (it may be above everyone’s).

Some take the view that the new alliance of monetary and fiscal profligacy will be enough by itself to drive inflation to a new, higher plateau. Albert Edwards of Société Générale summed this view up in his usual style a few weeks ago:

The pandemic recession has allowed policymakers to cross the Rubicon of fiscal rectitude to reach a new land — one where their existing monetary profligacy can now be coupled with fiscal debauchery. At a political level I do not believe there is any turning back now the sweet fruits of monetary-funded fiscal largesse have been plucked and tasted.

I’m not as sure the profligates will win the day, politically. But there are other factors to consider.

The economists Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan think that demographic change will tip the scales further toward inflation. Their work has done the rounds on Wall Street, so some readers will have made their minds up already; I wanted to touch on the arguments here, though, because it is the only case for the return of sustained inflation I have seen, outside of the “central bank and government co-ordinated money dump”.

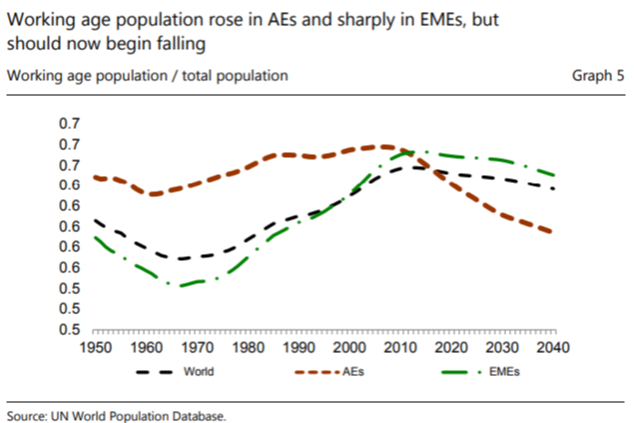

Goodhart and Pradhan’s core view is that prices have been depressed for three decades by globalisation, as production moved to low-wage countries, undercutting wages everywhere. As the populations of countries like China begin to flatline, though, wages there will rise at the same time as working-age populations in the developed world fall; workers will be in short supply everywhere, and globalisation’s deflationary effects will cease. “As the world ages, real interest rates will rise, inflation and wage growth will pick up and inequality will fall” they write.

This is simple supply and demand. As the supply of labour goes down, relative to available capital, the price of labour will rise, with other prices following.

Global ageing will have another effect, Goodhart and Pradhan think. It will reduce savings faster than it reduces investment, which will push interest rates up, as less capital will chase investment opportunities (healthcare spending by the elderly, particularly in China, will be the key driver of reduced savings). Higher taxes needed to keep social safety nets in place will be inflationary, too, as scarce workers will be in position to demand higher wages in response.

It is important to remember that, for this to matter a lot to investors, Goodhart and Pradhan only have to be a little bit right. A new inflation plateau at, say, 3-plus per cent would really make investors’ life difficult — for starters by forcing bond and stock returns into correlation, taking away a hedge that has worked for decades.

The natural response to the demographic argument is one word long: “Japan”. An ageing population didn’t increase inflation or real rates there. In fact the opposite happened. The Goodhart/Pradhan reply is that what matters is not demographics locally, but globally. Japan exported production when its workforce shrank. This from Pradhan in a recent interview:

Japan is a very open economy, but it’s very close to their gigantic neighbour, China. In fact, when you look at the timing, what happened in Japan is no surprise: right at the time that Japan’s demography turned south, China was busy disinflating the entire world.

As an aside, one interesting upshot of the Goodhart/Pradhan thesis is that there is a political conflict on the way, pitting workers against retirees:

The elderly will become a powerful political force as their cohort swells due to ageing. It is this political power that we think will keep administrations from reneging too much on their pension obligations. The prime working age population will be a dwindling cohort but they will possess an important commodity whose price is likely to stay on an upward trend — labour . . . The political divide of the future will be over the elderly protecting their social safety net and the working-age population their real post-tax incomes.

That sounds like no fun at all.

I am not a good enough economist to assess this argument properly. I’d be curious to hear what readers think. It seems to me, though, that Christopher Smart has put his finger on the right question. Are we going back, sooner or later, to exactly the same place we were before the pandemic (but with a higher debt load)? Goodhart and Pradhan give a principled case for thinking not.

Another word on shipping inflation

Two days ago I wrote about the cost of shipping from China, and whether it is going to stay high. Tony Foster, who runs Marine Capital, which manages investments in shipping assets, emailed in response. He thinks the higher prices will take a long time to unwind. We know there will be a lag before the supply of cargo ships catches up. But, surprisingly, efforts to decarbonise shipping is also a factor:

The big liner companies are chartering ships at current (very high) charter rates for five-year terms in order to secure tonnage. This illustrates a significant level of confidence. Supermarket firms are chartering ships themselves in order to ensure certainty of supply. The new ships ordered will, as you say, take at least two years to come through. The dry bulk [ship] market is constrained (as to new orders) because of perceived technology risk. Shipowners don’t know what the fuel of the future will be and what propulsion/ fuel storage systems will be required to meet decarbonisation goals. Despite tightening regulation (and impending carbon pricing), this disincentive to invest, exacerbated by rapidly rising steel prices and thus ship prices, fuels the continued strength in the freight market, even without extraordinary growth projections for commodity markets.

Expect this situation to be long-lived.

Foster’s note raises two questions for me: how inflationary is the fight against climate change? And what do central banks mean when they talk about “transitory” inflation?

And one more word on Jay Powell’s stock portfolio

Several readers responded to my approving summary of Dylan Grice’s view that Fed chair’s Jay Powell’s large holding of stocks should be expected to bias his policy judgment. The most common reply from readers was that Powell could put his wealth in a blind trust (which is the practice for officials in the UK, apparently).

Alas, this would not help. Powell could safely assume that whoever managed the tens of millions in his trust was not a complete idiot. Given that bonds yield very little, that would mean a big allocation to equities. That alone ensures that meaningfully tightening rate policy could make Powell significantly poorer.

I don’t want to sound like a damn communist here, but having a rich person as Fed chair is likely to distort policy. The Fed chair’s job is, on occasion, to tell markets that they can go pound sand. That’s a hard thing for a rich person to do.

One good read

A fine piece on rationality in The New Yorker. I would say it misses a key point. Rationality is not a state of mind, or even a set of habits. It is a commitment, a sort of religious vow. We’re all more or less inconsistent, ignorant and confused. Rationality is a commitment to try to do better, follow the rules, and acknowledge it when we fall short.

I spent too much time in graduate school.

Comments