In charts: why women in China are climbing high — or quitting work

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

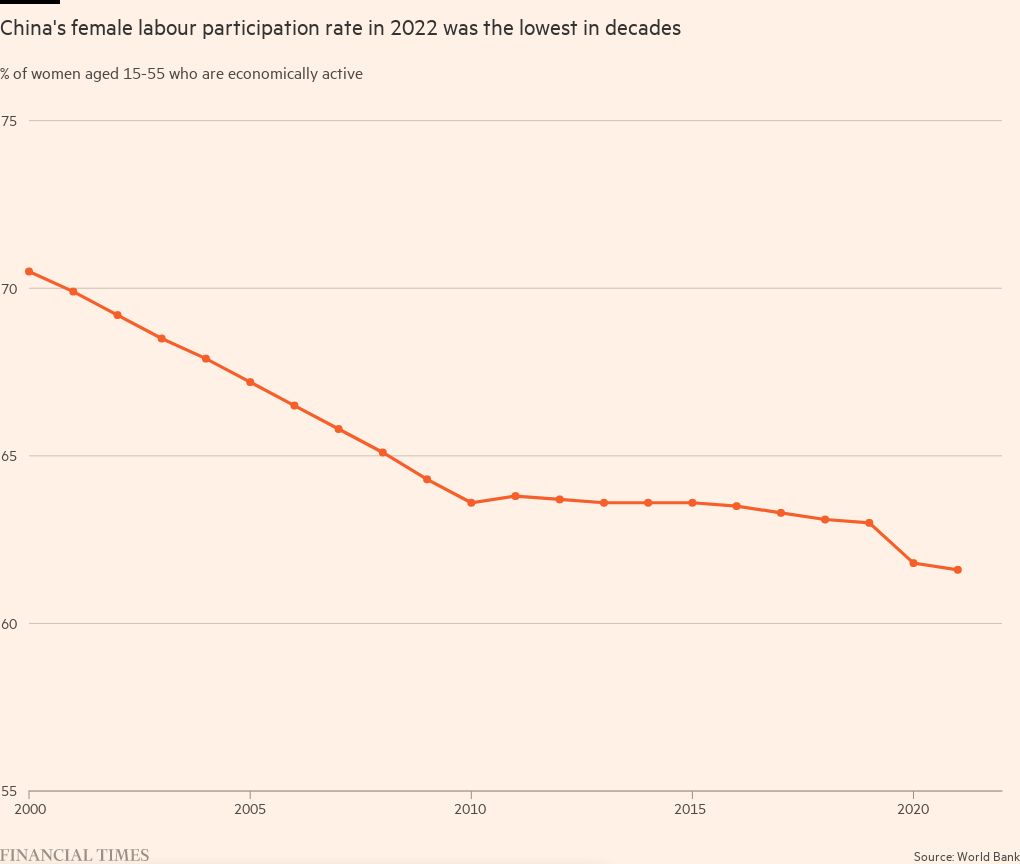

China’s once male-dominated workplace is rapidly embracing female leadership just as a growing proportion of women exit the job market.

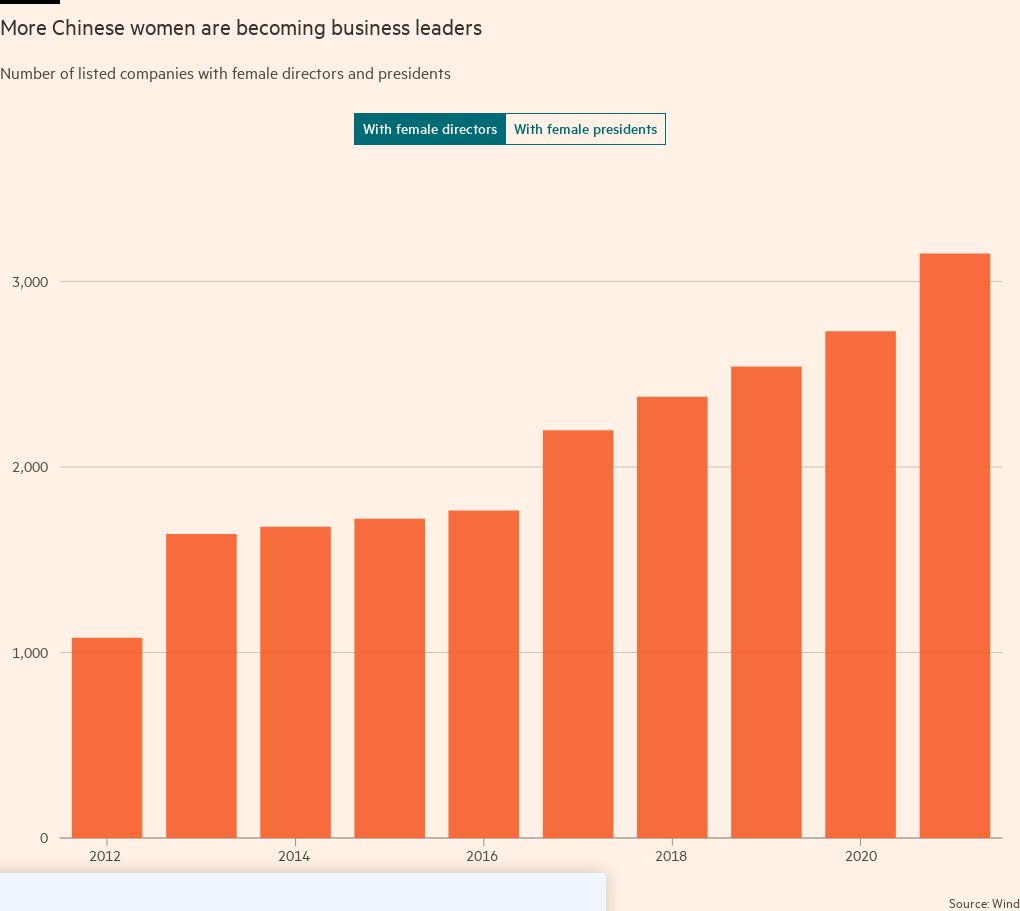

Data from the country’s listed companies, which are among its best managed, shows that the number of women presidents more than tripled to 241 in the decade ending in 2021. Meanwhile China’s female labour participation rate fell to a record low of 61.6 per cent from 63.8 per cent.

The contradiction underscores the precarious situation facing female professionals in the world’s second-largest economy, as they struggle to balance their career goals and family obligations.

“We have come to a point where women leaders, both in the middle and at the top, are taking off,” says Zhao Ying, co-founder and publisher of WhichMBA.net, a management education platform based in Shanghai. “But a lack of supporting networks in areas such as childcare has forced many female professionals to reduce, if not give up, their career ambitions.”

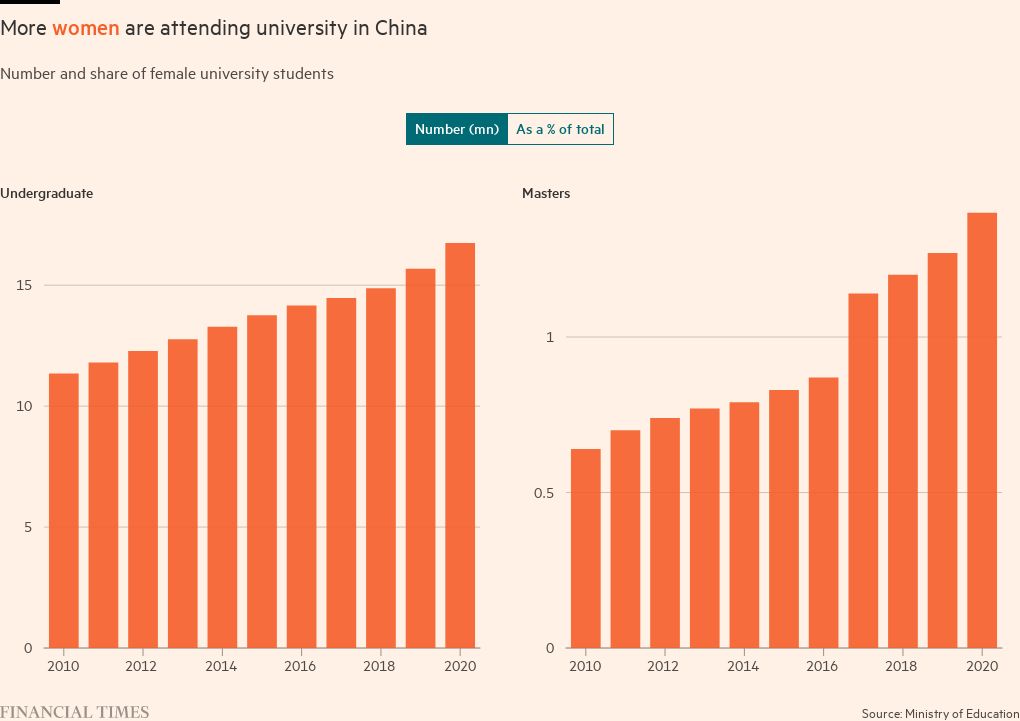

Chinese women’s growing influence in the workplace is due in part to their academic achievements. The number of female undergraduate students grew by almost half in the decade ending 2020, while the number pursuing master’s degrees more than doubled over the same period. Although men outnumber women in every age group, the reverse has consistently been the case in undergraduate and master’s programmes over the past 10 years.

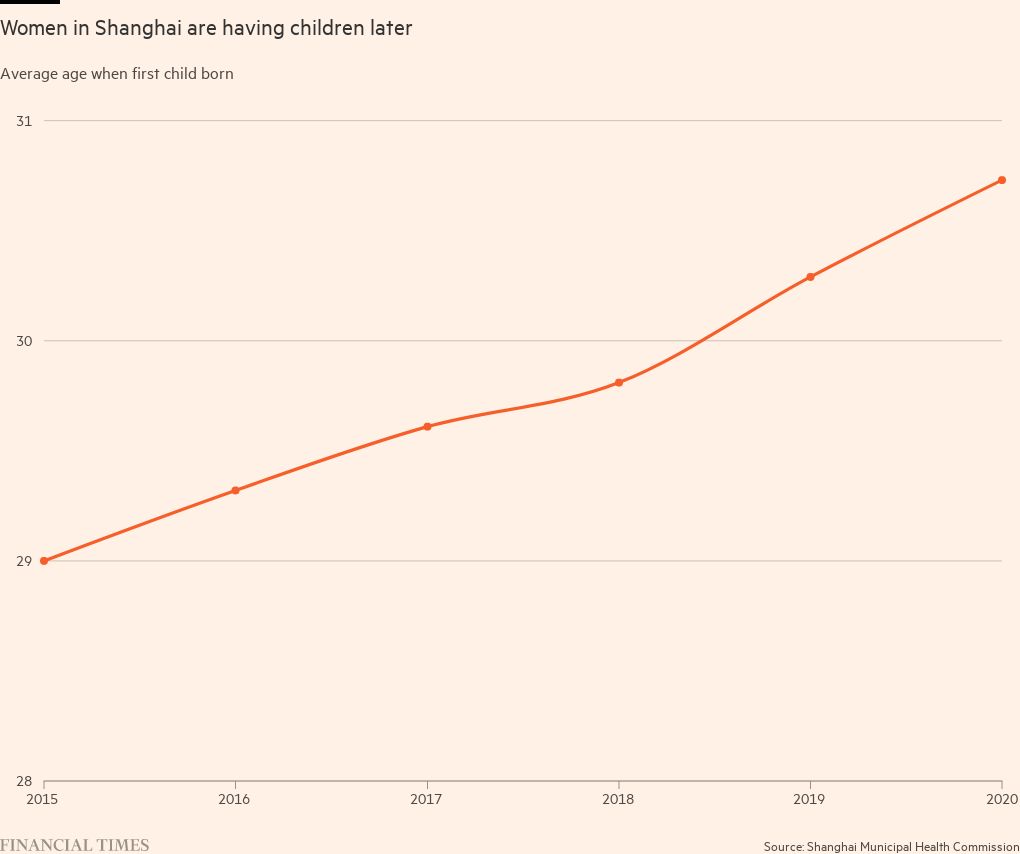

Women’s career advancement has also benefited from a plunge in the birth rate that has alleviated the burden of childcare. Births in China fell to a record low of 9.6mn last year from 16.4mn a decade ago, and newly registered marriages fell by two-fifths over the same period. Those who do have children are doing so at a later age. In 2020, for example, the average woman in Shanghai — a city with a reputation for being female-friendly, thanks to unusually supportive husbands — had her first child at about 31, up from 29 in 2015.

For many Chinese women, especially those in big cities, marriage and children, once top priorities in life, are giving way to economic independence and career success. He Dan, a 32-year-old manager of a wine bar chain in the central city of Changsha, says she has no plans to marry or have children because freedom matters more — along with the wealth that can buy it.

“I may never make enough money,” says He, whose annual income has increased tenfold over the past decade.

Other women, however, are choosing to quit full-time work to care for the family. The steady decline in female labour participation, say scholars, reflects the pressure on Chinese women to prioritise childcare so that their husbands can focus on their careers. This is especially the case in the current era of intensive parenting, with many hours of extracurricular activities and tutoring arranged mostly by mothers.

The government’s introduction of a two-child policy in 2016 — replacing the one child per couple policy imposed in 1979 — has put extra pressure on working mothers. Official data shows that more than half of China’s newborns in 2021 had older siblings, up from 39 per cent in 2015 (exceptions were permitted under the one-child policy).

The difficulty of juggling work and children is further exacerbated by a lack of government investment in affordable day care facilities. The upshot is that, while the falling birth rate has freed some women to scale the corporate heights, many mothers of young children feel they have no choice but to take long-term breaks from work even though they still long for a career.

In Nanjing, Zhao Lei, a former auditor, says she had to quit her job to care for her child, born at the end of 2021. “I’d never thought about being a stay-at-home mom,” says Zhao, 33, “but I couldn’t find anyone to look after my baby as my family members are not available and good nannies are difficult to come by.”

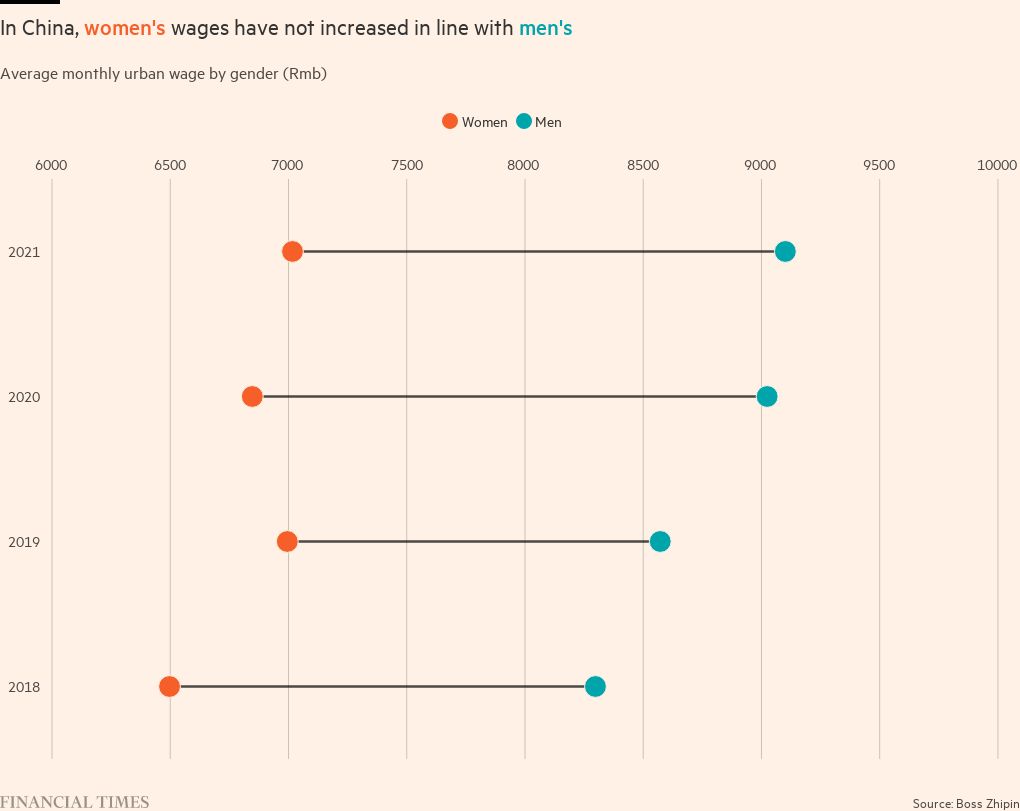

Chinese women’s disproportionate responsibility for childcare has contributed to a wide and persistent gender pay gap, with many private firms turning down female job applicants in case they go on to have children. According to Boss Zhipin, a Beijing-based online job search portal, the average urban wage for male workers between 2018 and 2021 was about 28 per cent higher than that for female workers.

“There is no way women can balance work and family until men do so,” says Zhao Lei.

Essay competition: win a free EMBA

The FT launches its annual Women in Business essay competition in partnership with the 30% Club and Henley Business School. The prize is a fully funded place on Henley’s part-time Executive MBA programme.

This year’s question is: ‘Affordable and flexible childcare is a challenge that concerns everyone. What role can employers and policymakers play?’

The deadline is May 22

More information: hly.ac/WiLscholarship

Comments