Soaring US ‘real yields’ pose fresh threat to Wall Street stocks

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

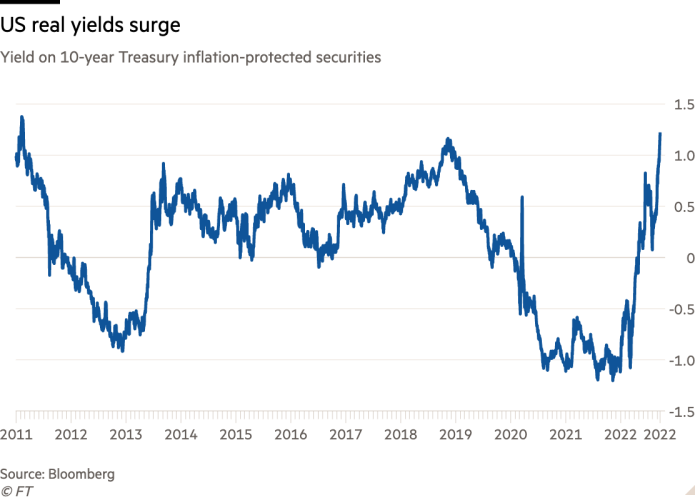

US real yields, the returns investors can expect to earn from long-term government bonds after accounting for inflation, have soared to the highest level since 2011, further eroding the appeal of stocks on Wall Street.

The yield on 10-year Treasury inflation-protected securities (Tips) hit 1.2 per cent on Tuesday, up from roughly minus 1 per cent at the start of the year, as traders bet the Federal Reserve will aggressively raise interest rates and keep them elevated for years to come as it attempts to cool inflation.

The sharply higher returns safe-haven government debt now offer have weighed heavily on the $42tn US stock market, given investors can find enticing investment opportunities with far less risk. Strategists with Goldman Sachs on Tuesday said that “after a long stretch”, investors buying Treasuries or holding cash would soon earn returns that have been “impossible” to come by for the past 15 years.

Real yields are closely followed on Wall Street and by policymakers at the Fed, offering a gauge of borrowing costs for companies and households as well as a scale to judge the relative value of any number of investments.

Those real yields fell deeply into negative territory at the height of the coronavirus pandemic as the Fed cut interest rates to stimulate the economy, sending investors racing into stocks and other risky assets in search of returns. That has reversed as the US central bank has rapidly tightened policy.

“What you see in the higher real rates is the clear expectation that the Fed is going to drain a tremendous amount of cash and liquidity out of the market,” said Steven Abrahams, head of investment strategy at Amherst Pierpont.

The Fed has already lifted its main interest rate from near zero at the start of the year to a range of 2.25 to 2.5 per cent. It is expected to boost it by another 0.75 percentage points later on Wednesday, with further increases bringing the federal funds rate to around 4.5 per cent by early 2023.

The Fed’s quantitative tightening programme, in which it is reducing its $9tn balance sheet, is putting additional upward pressure on yields.

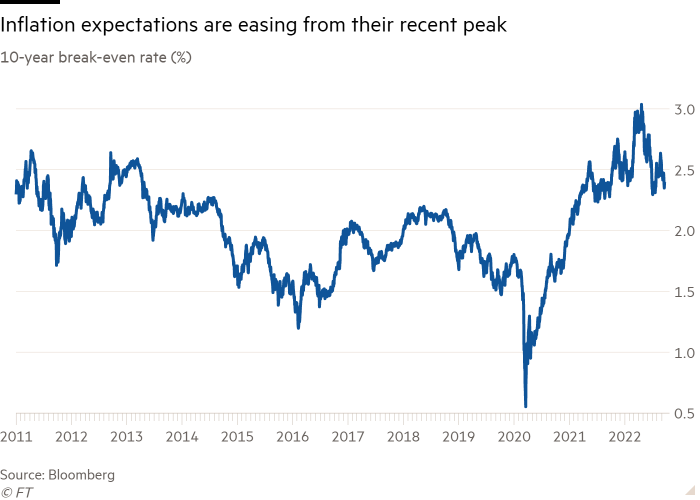

The jump in so-called real yields has been driven in part by expectations that the Fed will be able to bring inflation closer to its long-term target of 2 per cent in the years to come.

A measure of inflation expectations known as the 10-year break-even rate, which is based on the difference in yield on traditional Treasuries and Tips, has eased from a high of 3 per cent in April to 2.4 per cent this week. That would mark a dramatic decline from the August inflation rate of 8.3 per cent.

“What is important for growth equities is not whether the peak has happened in interest rates, but the fact that the discounting rate will remain higher for a longer time,” said Gargi Chaudhuri, head of iShares investment strategy for the Americas at BlackRock. “For the next 18 to 24 months, all of these companies’ valuations will continue to get discounted at that higher level.”

Fast-growing companies that led the rally on Wall Street from the depths of the coronavirus crisis in 2020 are under the most pressure from rising real yields. That is because higher real yields reduce — or “discount” — the value of the earning these companies are expected to generate years from now in models investors use to gauge how expensive stocks look.

Since the start of the year, the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite has tumbled 27 per cent. A recovery in the latter half of the summer has been all but obliterated as expectations of further aggressive Fed action have been cemented. The fall in unprofitable tech stocks, which had posted spectacular gains as investors chased high yields, has been particularly notable — with a Goldman Sachs index tracking such companies losing half its value in 2022.

“Very expensive and very unprofitable technology companies have been accustomed to discounting their cash flows at a negative rate and now have to readjust to positive rates,” Chaudhuri said. “Because your discounting rate is higher, the valuations of those companies will look less attractive, because they’re discounting at a higher level.”

Rising real yields may also put greater pressure on companies that took out leveraged loans, which are made to borrowers that already have significant debt loads. Interest rates on these loans are usually floating, meaning they adjust in line with the broader market as opposed to being fixed at a particular level.

“This is particularly bad news for leveraged borrowers,” said Abrahams.

Ian Lyngen, head of US rates strategy at BMO Capital Markets, added that “sentiment across the economy, in terms of risk asset performance and the perception of the impact on consumers, is closer to real yields than it has been to nominal yields”.

He said: “The logic there being that when adjusted for inflation, real yields represents the clear impact of effective borrowing costs on end users.”

Comments