Emerging market bond slump creates opportunities for investors

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

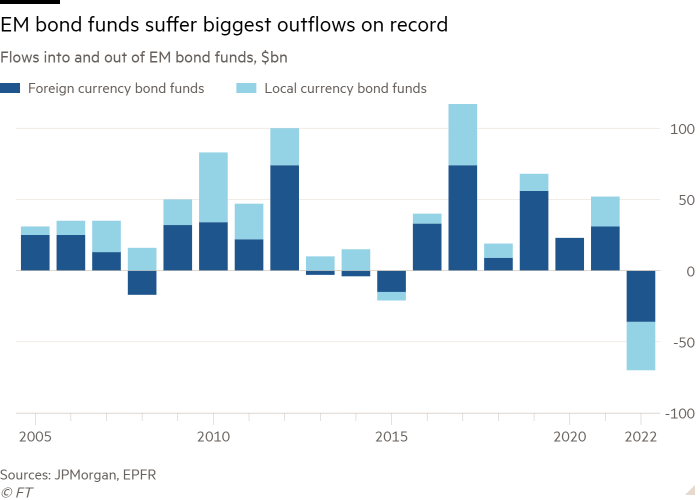

It has been a tough year for emerging market bonds. Investors pulled a record $70bn from funds investing in EM debt between January and the end of September — a period that included only seven weeks of net inflows.

Those relentless outflows signal how badly markets have been battered in 2022, with the soaring US dollar and rising global interest rates sucking money out of EM assets. The question now is whether inflation and interest rates are near their peak, creating an opportunity for bond prices to rise again.

Many emerging economies had a promising start to the year. A recovery from the pandemic seemed well under way and several EM central banks had acted quickly to get inflation under control, raising interest rates from as early as the first quarter of last year.

But Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine changed that.

“If the war hadn’t happened, we would have seen inflation peaking in the first quarter and, by now, it would be falling across the board,” says Simon Quijano-Evans, chief economist at Gemcorp Capital Management. “But, thanks to the invasion, energy and food prices skyrocketed, catching everyone by surprise.”

Soaring food and fuel prices are especially toxic for consumers in developing countries, where staples make up a bigger proportion of household spending than in advanced economies.

Price rises forced many EM central banks to act early and aggressively in an attempt to contain inflation, raising interest rates and making bonds less attractive.

Some commodity-producing economies were able to offset the damage thanks to the rise in earnings for their exports. But then they, too, were hit by the surge in US inflation and the sharp upswing in global interest rates.

The result has been an extraordinary turnround in the bond market. In the six years to 2021, money poured into both local currency and foreign currency EM bond funds at an average of more than $50bn a year. During the first three quarters of this year, money flowed out at the fastest rate since JPMorgan began reporting the data in 2005.

There is no immediate sign of change. Milo Gunasinghe, emerging markets strategist at JPMorgan, says he expects US and global financial conditions to tighten for the foreseeable future, keeping the bar high for inflows into EM bonds.

He notes that the balance sheets of central banks in the US, the eurozone, Japan and the UK surged by about $8tn during 2020 in a massive injection of liquidity into global financial markets during the pandemic.

Since early 2021, that stimulus has been almost entirely reversed, pulling the rug from under bond markets. JPMorgan expects a further $1.7tn contraction in those central bank balance sheets over the coming year.

More from this report

For many emerging and so-called frontier economies — the smallest of the emerging markets — financial markets are already, in effect, closed. This year, at least 20 low- and middle-income countries have seen their foreign currency bond yields rise to a level more than 10 percentage points above those of comparable US Treasury bonds.

Spreads at such high levels are often seen as an indicator of severe financial stress and default risk. Zambia defaulted early in the pandemic. Sri Lanka followed this year. Lebanon, Russia, Belarus and Suriname have also defaulted. More defaults and debt restructurings are likely — the World Bank and others have warned of a coming wave of defaults.

One result is that the number of sovereign and corporate bonds being issued by emerging markets has collapsed.

Sergey Dergachev, head of EM corporate debt at German asset manager Union Investment, says sovereign and corporate bond issuance was worth about $670bn during the full year of 2021 but fell to $270bn in the nine months to September this year.

With many issuers retiring their outstanding bonds rather than refinancing with new issues, he says total foreign currency bond issuance from emerging markets will be negative this year, by about $200bn, compared with last year.

However, this has its advantages for investors, says Dergachev. “First, there is not the huge oversupply of previous years. As an investor, that means you can look at issues more carefully and be more selective,” he says.

In addition, bond investors have been able to capture significant premiums on new issues in 2022, with prices of many issues this year rising about 0.4-0.5 per cent before falling back, says Dergachev.

But, for a meaningful turn in the bond market to take place, inflation and interest rates globally will have to fall.

Quijano-Evans believes the peak in inflation is getting close. If so, the potential for currencies and bond prices to recover will be that much greater in emerging than in developed markets, he notes, because the falls in the former have been so much larger.

He also expects a concerted effort to rein in the dollar’s destabilising surge.

“It is in everybody’s interests to stop this massive appreciation of the dollar,” he says. Quijano-Evans expects global central banks, including the US Federal Reserve, to act together to stem its rise.

“When that news comes out, we will see a huge turn in the dollar and obviously EM currencies and assets will benefit.”

Comments