Fish farms bring former luxuries within reach of many — at a price

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

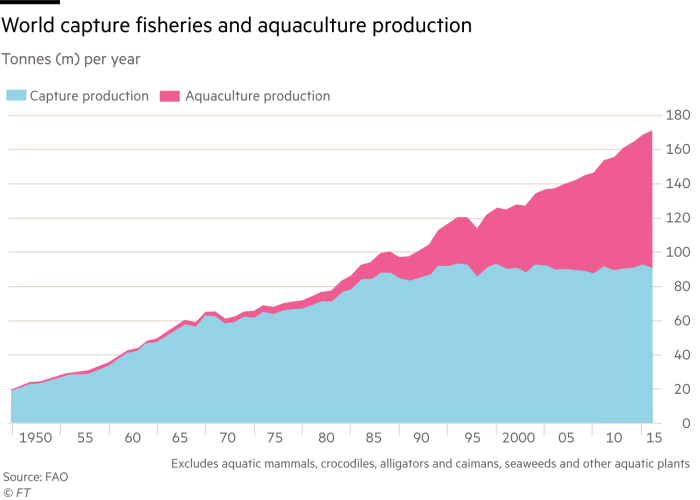

The rise of fish farming has been one of the biggest revolutions in food supply of the past half century, with annual global aquaculture output soaring from under 2.5m tonnes in 1970 to over 80m today, according to UN data.

The increase in supply has helped make fish and shellfish more affordable for consumers around the world. It has also democratised consumption of former luxuries and helped ease the strain on hard-pressed wild stocks.

Yet this is hardly an industry that can rest on its laurels. A global review of fishing published this year by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization said growth in farmed fish output is slowing.

Annual expansion in global aquaculture production will slow from 5.7 per cent between 2003 and 2016 to 2.1 per cent between 2017 and 2030, mainly because of reduced growth in China’s huge inland fish farming sector, the FAO found.

That means aquaculture growth between the mid-2010s and the early 2020s will cover only 40 per cent of the expected global rise in demand for fish, leaving a gap between demand and supply of 28m tonnes.

“Global aquaculture would need to grow 9.9 per cent per year in order to fill the world fish demand-supply gap,” the FAO said.

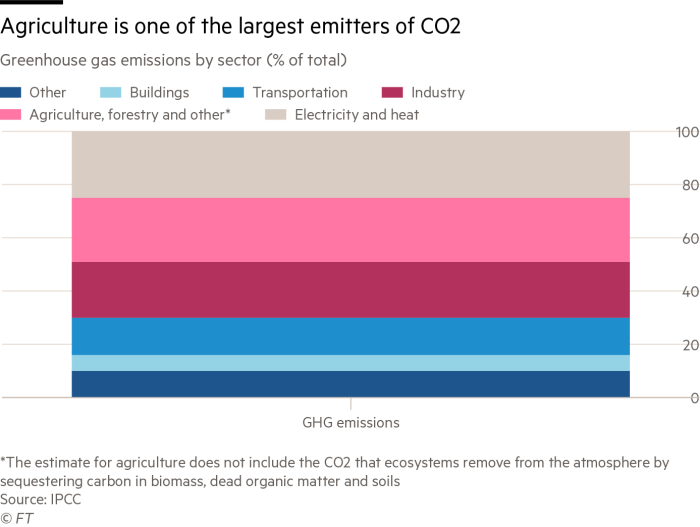

This gap presages not only more pressure on wild stocks — which are already either overfished or at maximum levels for sustainable exploitation — but a shift to more carbon-intensive forms of food production.

Aquaculture’s greenhouse gas emissions associated with climate change are just 5 per cent of those from agriculture, according to research cited by the FAO.

Expansion of fish farming faces major obstacles, however. Finding space for inland aquaculture is increasingly difficult, while worries about the environmental impact of offshore fish farming have also grown.

The fish farms dotted around Scotland’s scenic western sea lochs and islands offer a telling test case of the wider industry challenges. Salmon reared in the pens in the shadow of heather-clad hills have become one of the country’s biggest food brands. Scottish salmon exports outside the UK were worth £600m in 2017, according to the Scottish Salmon Producers Organisation, up 35 per cent compared with the year before.

The Scottish government has set out ambitions to double the total economic contribution of the sector from £1.8bn in 2016 to £3.6bn by 2030. But the fish farming industry has been subject to growing accusations that it is damaging the marine environment. Animal welfare activists complain that rearing salmon in densely populated pens means unacceptable levels of parasite infestation and disease.

“Scottish salmon farming is an environmental and welfare nightmare,” says Don Staniford, director of activist group Scottish Salmon Watch.

In November Scotland’s state environmental watchdog unveiled plans for a “major overhaul” of its regulation of the fish farming sector, in an apparent acknowledgment of activist complaints that current controls are too lax.

The Scottish Environment Protection Agency’s proposals include closer monitoring of waste from fish farms, tighter controls on medicinal chemicals and creation of a new enforcement unit intended to ensure “compliance is non-negotiable”.

According to Sepa, there is “increasing evidence” that fish farms lead to larger numbers of sea lice — small creatures that eat the mucus, skin and blood of salmon — among wild salmon. In large numbers, sea lice can kill salmon and conservationists say fish farms are contributing to the collapse of wild populations in west coast rivers. The population of Scottish Atlantic salmon has declined by more than half since the 1960s, to about 600,000 in 2016.

Fish farmers acknowledge sea lice are a big problem but they insist the industry can cope with the challenge. A favoured new method is to keep “cleaner fish” such as Ballan wrasse and lumpsuckers in their pens, where they eat the sea lice off the salmon’s skin.

But a recent report on fish farming published by the Scottish parliament’s rural affairs committee highlighted concerns that unregulated capture of wild wrasse for use in fish farms could damage local ecosystems.

One diving business owner told the committee that a diminution in the wild of wrasse, which normally eat octopus eggs, meant more shellfish were being eaten by octopuses, potentially hurting local fishermen of shellfish.

The committee urged the government to consider regulation of the fishing of cleaner fish to preserve wild stocks. It also called for action to move fish farms sited near migratory routes or in slow-flowing inshore waters to locations where they were less likely to pass sea-lice to wild salmon.

In conclusions likely to resonate with many in the global aquaculture business, the committee said that for fish farming to grow sustainably, policymakers needed to “raise the bar” with regulation that would ensure fish health was better protected and environmental impact kept to an “absolute minimum”.

Maintaining the status quo “is not an option,” it said.

Comments