In charts: Global progress on energy efficiency

Simply sign up to the Renewable energy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

First, the good news. Global investment in energy efficiency is on the rebound.

The Covid pandemic subdued economic activity and cut capital spending on environmental projects in the past two years. But recovery programmes across major economies are now boosting expenditure on measures designed to deliver energy savings.

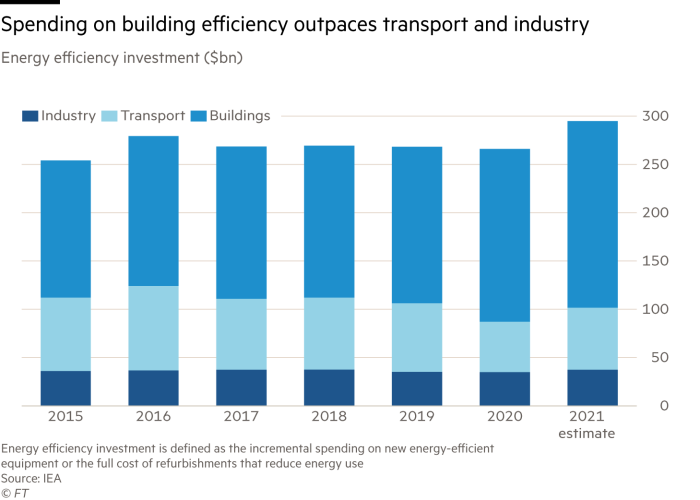

The latest detailed report on the topic, published by the International Energy Agency last month, suggests that public and private investment in energy efficiency is expected to increase by 10 per cent globally, to just above $290bn — a record level — with much of it concentrated on the transport and buildings sector (see below).

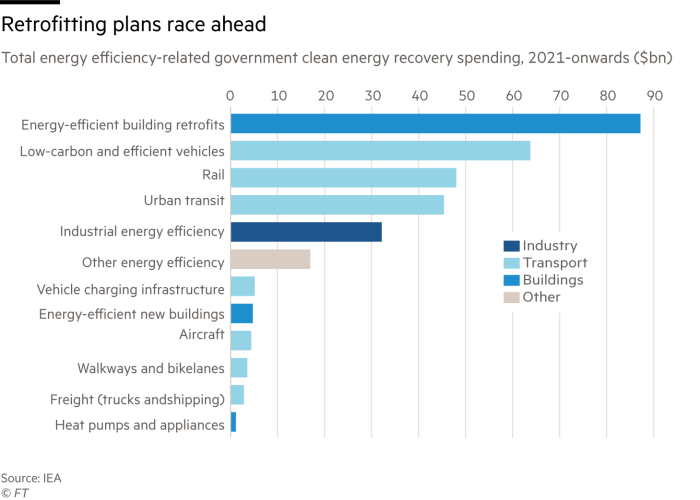

More is to come. Data collated by the agency up to the end of October suggests that the amount of capital mobilised by recovery schemes targeted at clean energy measures is set to jump by an average of $400bn a year in the three years to 2023.

More than half of this increase is expected to be spent on energy efficiency measures in buildings, industry and cleaner, low-carbon transport.

Now, the bad news. Existing levels of spending must double again to achieve the ambitions set out by the Paris Climate Agreement and reinforced by last month’s UN COP26 summit in Glasgow.

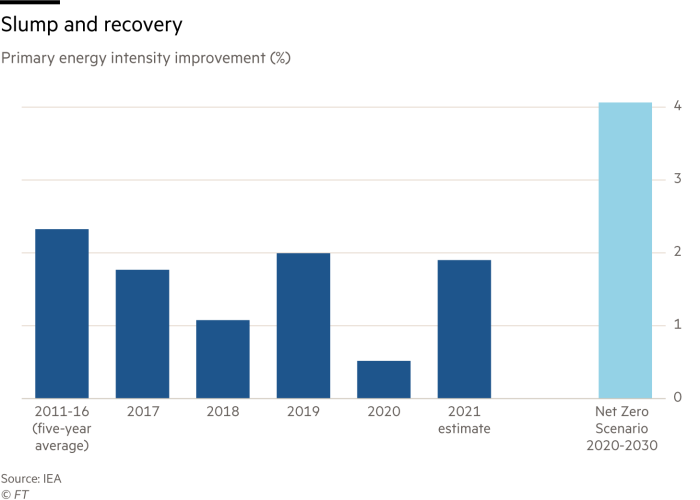

And, while global progress on energy efficiency has recovered to its pre-pandemic pace, it remains well short of what would be needed to keep the world on track to avoid climate disaster by mid-century, according to the report.

As coronavirus spread around the world, 2020 became the worst year in a decade in terms of slowing energy use. In many major economies, the Covid pandemic shifted the weight of economic activity away from services hit by lockdowns and towards more energy-intensive industry. However, the rate of improvement in global energy intensity — an indicator of how much energy is needed to power economic activity — is expected to recover to 1.9 per cent.

Unveiling the report, Nick Howarth, a senior policy analyst at the IEA, said: “While it is good to see energy efficiency trends get back on track this year, there is still some way to go to align with climate targets — with the rate of improvement needing to double over the next 10 years, on average, to be consistent with the 4.2 [per cent] annual improvement that would align the IEA net zero by 2050 scenario.”

Fatih Birol, the IEA’s executive director, has said it is essential that policymakers redouble their efforts to damp demand for energy — particularly that derived from fossil fuels — across the full range of economic activity.

“A step change in energy efficiency will give us a fighting chance of staving off the worst effects of climate change while creating millions of decent jobs and driving down energy bills,” he commented, when the report was published. “We consider energy efficiency to be the ‘first fuel’ as it still represents the cleanest and, in most cases, the cheapest way to meet our energy needs.”

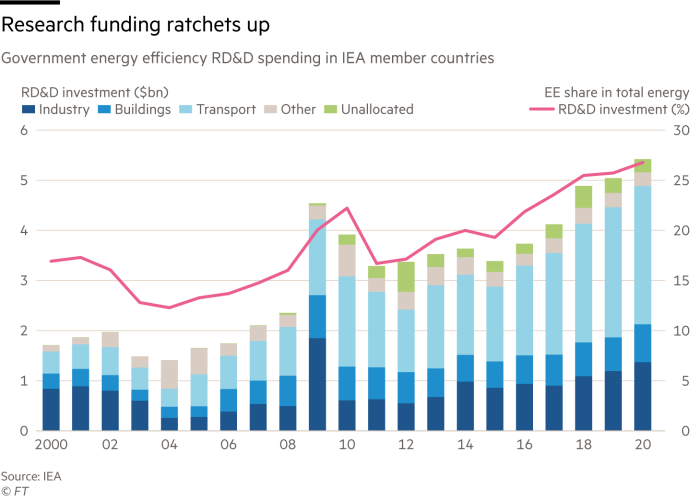

So far, there has been steady progress in the amounts spent on researching energy efficiency in the richer countries that support the IEA. The shock of the financial crisis of 2008 also prompted some governments to throw more money behind energy saving efforts, as part of their recovery plans (see below).

Research suggests that public and private investment in efficiency schemes has already driven down carbon emissions and energy bills across the globe.

Without action to improve efficiency, last year the world would have been using 13 per cent more energy than two decades ago and energy-related carbon emissions would have been 14 per cent higher.

Looking ahead, the IEA argues that, if the world were to implement the cost-effective energy efficiency opportunities available today, energy demand could be reduced by 15 per cent in 2040. The transport sector (38 per cent) accounts for the largest share of the future energy savings, followed by buildings and appliances (33 per cent), and industry (29 per cent).

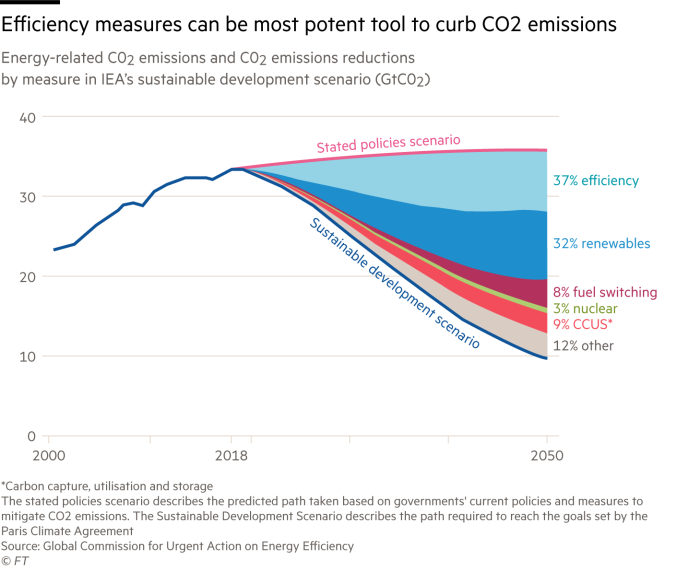

In fact, the report suggests that the aggregate impact of maximising energy efficiency schemes in the coming decades would make more impact than the deployment of renewable energy, or the use of low-carbon nuclear power generation, or the development of carbon capture and storage, or the implementation of any emission-cutting tactic (see below).

However, the IEA notes that commitments to achieving these gains remain patchy across the world. “Approved energy efficiency spending by governments is regionally unbalanced, with the majority of spending coming from advanced economies,” it says.

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

Comments