Art with a conscience: Goodman Gallery opens in London

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

At a moment when some large galleries are under fire for expansion strategies that endanger smaller peers, it’s unlikely that the London inauguration of a new branch of Goodman Gallery will receive anything other than a warm welcome. The South African gallery, which has branches in Johannesburg and Cape Town, inaugurates its new space in Mayfair’s Cork Street on October 3.

The first dealer to sign a permanent lease for Pollen Estate’s ambitious redevelopment on the thoroughfare — historically a home to blue-chip galleries — the new outpost will take up 5,730 sq ft across the ground and basement floors of the building, which was designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

Goodman Gallery opened in Johannesburg in 1966. Its founder Linda Givon (then Goodman) is described by present owner Liza Essers as an “amazing woman, very brave, very dynamic”.

Without these qualities, Givon would never have opened such a gallery at a moment when apartheid was tightening its grip. Yet Goodman Gallery welcomed black artists, one of very few galleries in the country to do so. When the gallery had openings, her black guests had to pretend to be waiters if security forces paid a visit.

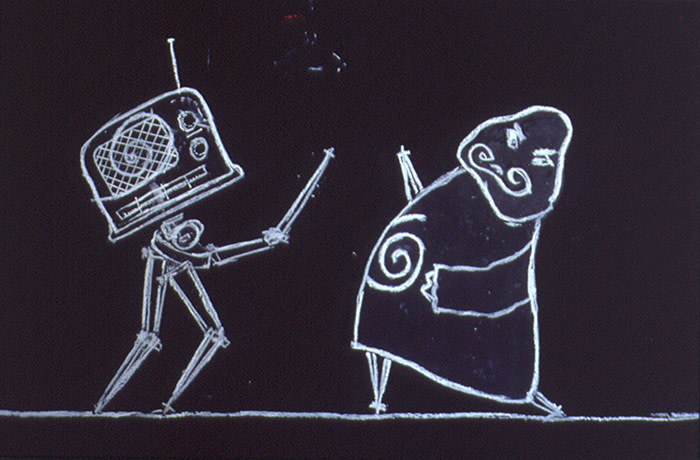

By the time Essers took over in 2008, the gallery had established itself as “a quasi-institutional space”, as well known for community projects such as education, publishing and public programming as for its championship of artists such as David Koloane and William Kentridge.

Essers, the daughter of a Libyan refugee, had previously worked in the corporate sphere and as an independent film-maker. But she knew that what she wanted most was to “work in a space where I could effect social change . . . ” A phone call opened the door. Essers had collaborated with the gallery owner on various projects. Now Givon, who had health issues, was looking for someone to take over.

“I was blessed that she chose me,” says Essers, who talks to me over the telephone from Johannesburg.

The Cork Street move is one more step on an international journey to which Essers has been committed from the outset. “Obviously when it started it was important for the gallery to represent South African artists,” she explains. “But when I took over I wanted to shift the dial to become ‘artists plus’,” she continues, and to open up to practitioners from further afield.

Today, her stable includes Chilean-born Alfredo Jaar, British-Nigerian Yinka Shonibare, and the American Carrie Mae Weems, as well as artists from different countries in Africa such as Zimbabwe-born Kudzanai Chiurai.

By opening in London, Essers hopes to increase the gallery’s presence in “the international discourse” of the art world and ensure that its artists are “written into art history” by cultural guardians such as Tate, whose proximity, she acknowledges, is another motivation for choosing the British capital.

Given her desire to cross borders, it is not surprising to hear that one of Essers’ pet hates is hearing her gallery pigeonholed as an “African art gallery”. She feels that regional-focused shows and art fairs contradict “what the power of art is — it’s about making connections, not about being divisive and distinctive. We need to be looking at our shared histories.”

Little wonder many artists are enthusiastic to collaborate. “Goodman is contributing to global conversations about art history, politics and critical thinking,” observes Chiurai. “That’s why it’s been attractive to young artists.”

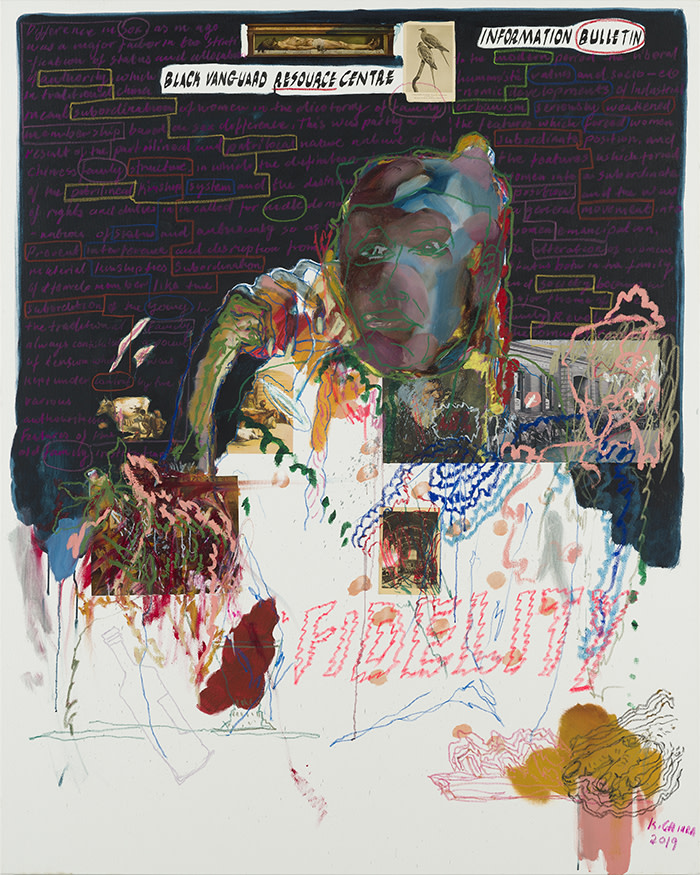

Chiurai, 38, has been with the gallery for eight years. His work has been exhibited at MoMA, and Documenta. But in Africa, his political sensibility has posed challenges. At one point, while based in South Africa, it became too risky to return home to Zimbabwe after he made work critiquing Robert Mugabe. “There was a law that said you couldn’t use the president’s image in a derogatory manner,” he recalls.

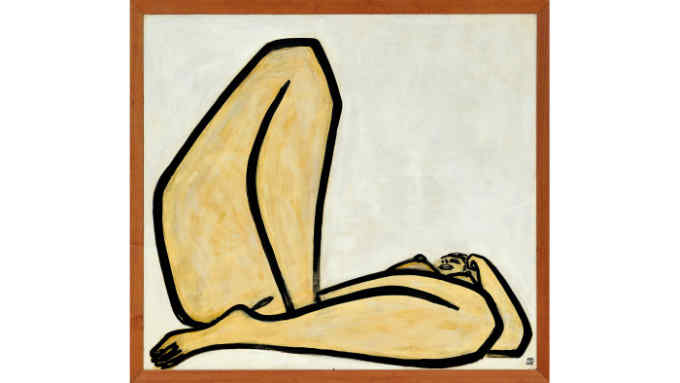

Chiurai’s film, We Live in Silence: Chapters 1-7 (2017), the third element in a trilogy that explores the impact of colonialism, is on show during Goodman’s opening week in the inaugural exhibition, I’ve grown roses in this garden of mine. With work by 22 artists, including Ghada Amer and Gabrielle Goliath, the show takes its title from Goliath’s latest work “This song is for . . . ”, a cycle of dedication songs chosen by survivors of rape which sets a framework for art that explores ideas of personal and political healing and repair.

The gallery does more than show work that advocates recovery. Currently, for example, they are collaborating with an organisation in Johannesburg, the Witkoppen Health and Welfare Clinic, to raise funds for supporting under-serviced communities.

For Jo Stella-Sawicka, co-director with Emma Menell of the London branch, Goodman’s public activities were crucial in her decision to join them. “You don’t hear about galleries with a social purpose,” says Stella-Sawicka, who was previously artistic director at Frieze Art Fair. “Goodman is [unusual] in that respect.”

Stella is excited to share news of the gallery’s plans for their Frieze booth, which she describes as an “intergenerational conversation”. For artists in South Africa, older practitioners, teachers and mentors have provided vital sustenance. The Frieze stand, says Stella, will see “three different presentations, so we will change the stand three times” between a “really established figure and a younger emerging artist from Africa and the diaspora”.

Another radical move by the London gallery is the plan to donate the space free of charge to other dealers for around six weeks every year.

Most probably, Essers says, these galleries will come from the global south and will already be “making a difference in society” but have limited opportunities for commerce. Essers agrees that this is “contrary” to the competitive nature of most dealers’ relationships, where mega-galleries poach artists at the moment they start to become successful from smaller brethren.

“The big galleries come in and say: ‘Oh, African artists are hot, Middle Eastern artists are hot [ . . .] and the artists are taken up by [them]’,” says Essers. “This is a different way. I’m saying I will support what you do.”

Given the philanthropic nature of such activities and the political content of the work Goodman sells, it’s impossible not to wonder how the gallery sustains itself. Essers is philosophical. “It would be easier to sell pretty paintings but [sales] are not what drives me,” she explains. “The work we have is much more challenging. It’s about leaving a history or a legacy.”

But how does she make a profit? “You do the work, you act with integrity, and the rest follows.”

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen and subscribe to Culture Call, a transatlantic conversation from the FT, at ft.com/culture-call or on Apple Podcasts

Comments