The role of the corporation in society

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

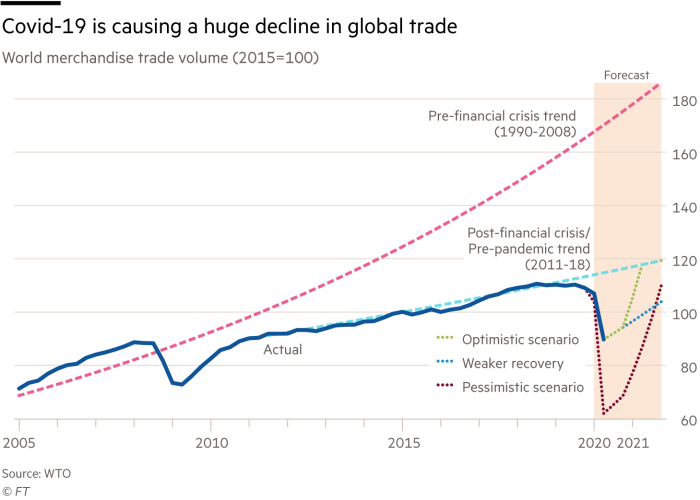

The coronavirus pandemic has forced companies to adapt, affecting everything from the minutiae of daily tasks to the fundamental way they view their businesses and make money. The pact between the corporation and society has also changed.

Lockdowns imposed by governments worldwide have led to near-universal homeworking for office staff. Businesses for which remote working is impracticable have closed, with a devastating effect on employment.

The plight of workers is most stark in the US, where joblessness figures have soared: one in five American workers filed for first-time unemployment benefits between mid-March and May. Governments have had to take action on an unprecedented scale, both to extend funding to struggling companies and to underwrite workers’ salaries.

The handing out of taxpayers’ money has put business practices and their broader effect under intense scrutiny. The accompanying requirement is that companies behave with greater responsibility.

Spurred by the virus, and occasionally by public opprobrium, many companies are now more supportive of their workers and suppliers. Others have seized the opportunity to help broader society, for instance by turning over factories to make medical supplies.

A poor response by some groups has made headlines. Amazon fired employees who complained publicly about inadequate protection in its warehouses; JD Wetherspoon, the British pub chain, refused to commit to paying furloughed workers before a government assurance that their wages would be covered; top managers at Disney were criticised for failing to adequately “share the pain” with their many thousands of laid-off workers, although both the executive chairman and chief executive gave up part of their pay.

Once the virus recedes, will the corporation — and with it our idea of what it means to do business — have changed fundamentally? Will the old school of purely financially driven capitalism have surrendered to societal pressure? Will we have a new view of the role of companies in society, especially the hierarchy of stakeholders and investors? Will the demand to imagine a more inclusive form of capitalism have gained further traction?

The attitudes forged during the pandemic may or may not last. Hopes for a better world may be sacrificed to recovery at any cost, and the changes we have seen so far may be viewed simply as expedient responses to temporary upheaval.

To explore these issues, the Financial Times hosted its second Future Forum think-tank event, entitled the Role of the Corporation in Society. On May 19 2020, participants gathered via their computer screens to see Professor Colin Mayer, of the Saïd Business School at Oxford university, and Martin Wolf, the FT’s chief economics commentator, debate a range of ideal and realistic outcomes.

This report examines which aspects of corporate behaviour could change for ever as a result of the pandemic, and which are unlikely to be affected.

-----

Before the pandemic

In the opinion of business executives who shared their views with the FT Future Forum think-tank, trust in business was low before the emergence of Covid-19. Matthew Rees, group head of indirect taxes at Schroders, was not alone in blaming this in part on “a hangover” from the financial crisis of 2008.

To try to regain public confidence, companies had begun to pay attention to the concept of responsible capitalism. Among notable proclamations was the August 2019 pledge by Business Roundtable, an organisation that comprises 200 US chief executives, in which it said it would abandon shareholder primacy and redefine corporate purpose to create an economy that “serves all Americans”.

Regulations regarding environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure added to the pressure. These were already changing corporate practices, although the lack of a global reporting standard was sometimes used as an excuse to treat ESG as “too hard” to address.

Regulators also required pension funds to act. Last year the UK directed pension fund trustees to consider ESG factors or give a reason why they had not.

Some investors were already on board. Investment in ESG strategies has grown rapidly, with the Global Impact Investing Network estimating the value of dedicated impact funds at more than $500bn in 2019.

Beyond dedicated funds, money managers have arguably been ahead of consumers in pushing for responsible corporate behaviour in areas such as climate change and executive pay.

In January, Larry Fink, chairman and chief executive of BlackRock, announced that corporate responsibility would become a focus of the fund management house. The company said this decision had paid off in performance during the current crisis.

Even before the pandemic, good governance was considered a core business requirement. Environmental issues had also become more prominent as young people engaged in the school strikes championed by Greta Thunberg, the teenage climate-change campaigner.

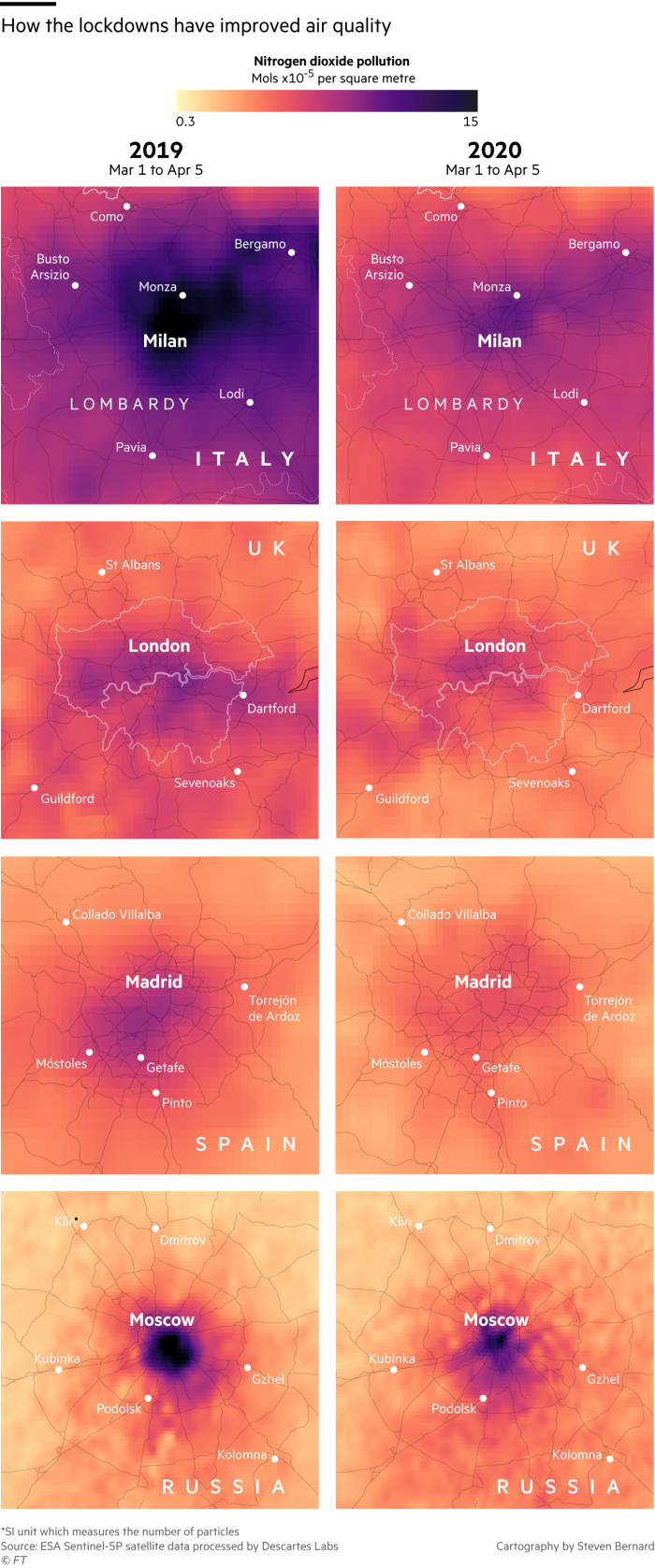

The “social” component in ESG has been probably the most neglected of the three. The questions of workers’ rights and companies’ broader effect on society had been under-explored. The coronavirus crisis has shifted this balance. Even as the sky has become cleaner as a result of the pause in economic activity, the “S” in ESG has gained visibility.

-----

“Ecosystem” responsibility

• Commitments to honour procurement contracts

The collapse in consumer demand has rippled along supply chains. The response of corporate customers has varied. Clothing company H&M made an early pledge to pay for contracted goods, including those in production, while its rival Primark extended limited support to its suppliers only after bad publicity. Those in non-discretionary areas have been more able to be supportive. Iberdrola, the electricity utility, said it was forging ahead with capital investment and had accelerated procurement from suppliers.

After the virus: Ecosystem support, notably that driven by consumer disquiet, is unlikely to last. Even assuming that shoppers’ personal circumstances stabilise, people are more likely to want to stretch their meagre dollar than feel sympathy with an out-of-sight worker. Witness the scrum in Britain when Primark reopened its doors on June 15. Diversification of sourcing as a way to spread the risk of disruption will gain in importance, with the position of suppliers in low-skilled sectors likely to become more precarious. Supply-chain relationships in high-tech industries are harder to replace and these demand a longer-term collaborative approach. This, however, did not prevent Rolls-Royce engaging in a public spat with its suppliers over pricing in May.

-----

Financing

• A shift in funding priorities

The attitude towards different forms of capital has shifted dramatically. While governments have been generous with bailout loans, restrictions in the UK, for instance, have disqualified some over-indebted companies, many of which are backed by private equity. In response to government prodding, and often as a condition of receiving money, many companies have scrapped plans to give dividends and buyback is now a dirty word. One respondent to the Future Forum survey was scathing about the US airlines’ $25bn bailout, observing that “these businesses were allowed to take advantage of stock buybacks for years”. Meanwhile, companies in a position to do so have been raising more equity, facilitated by regulators’ loosening of equity issuance restrictions.

After the virus: In the medium-term, companies may be inclined to manage their balance sheets more conservatively. It is even possible that they will consider permanent improvements to their capital structures to the extent desired by Prof Mayer, who argued in favour of higher reserves to provide a buffer against crises. Certainly, shareholders have been primed to expect lower returns, making equity a cheaper funding option. Governments hold the key to change. Regulation aimed at building balance-sheet strength, similar to that imposed on financial companies after 2008, may be required. Governments may also seek a return on the bailouts funded with taxpayers’ money. A trade-off between corporate recovery and shareholder (that is, taxpayer) returns would not be easy to manage.

-----

Taxation

• Bailouts for struggling companies.

In response to the pandemic, governments worldwide have pumped billions of dollars into their economies. The trust that had been vested in corporations to fulfil consumer needs and, increasingly, provide public goods has given way to a reliance on the state — notably with governments underwriting the salaries of furloughed workers. Tax was cited by Future Forum participants as a factor behind the erosion of trust in companies, especially tax evasion or failure to pay while still expecting state handouts.

After the virus: Alan Manning, professor of economics at the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE, drew parallels between the bailouts and insurance. He noted: “You can’t get the payback if you don’t pay the premium, but they haven’t been paying the premium.” He expected that tax rates would have to be re-examined, although this could prove difficult given that “corporations in their tax affairs are very mobile internationally”.

-----

Workers and working practices

• Remote working

The pandemic has hastened the digitisation of the office, with distance-working for office staff now the norm. According to Just Capital, an organisation that ranks US companies by stakeholder issues, more than two-thirds of America’s largest public employers have put in place remote or modified working practices. A significant number of executives responding to the Future Forum think-tank survey said they had increased communication with workers because of the pandemic: far from disincentivising contact, remote working has done the reverse.

After the virus: The knowledge that office staff can work from home without unduly compromising performance, and with the potential for reduced costs, will change working practices for good. A survey by PwC found that more than two-fifths of chief financial officers from 288 companies planned to make remote work a permanent option for roles that allow it. The effect could have a downside. As one Future Forum participant asked: “With technology efficiencies and perhaps diminished barriers in a ‘work from anywhere’ era, how many jobs will not come back post-Covid?”

• Worker benefits

Data from Just Capital show that four of the top five stakeholder issues in the US relate to worker conditions. These include paying a fair wage and providing benefits and ensuring that employees’ work-life balance is tolerable. As a result of the virus, more than two-fifths of America’s top 100 companies have offered paid emergency sick leave. In France, the food company Danone pledged to guarantee employees’ salaries until the end of June; it has also extended health and childcare cover and acted to ensure factory workers are as safe as possible.

After the virus: Companies whose business has remained stable or increased because of the virus will be finding it easier to treat their workers well, but Prof Mayer suggested that how companies look after employees now will be essential to their post-crisis recovery. Clifford Chance, the law firm, agreed. It noted that the pandemic had shown that “without a healthy, resilient team we cannot support our clients and the business has no future”. It is hard, however, to see how those lucky enough to keep their jobs through the pandemic — and more than 40m in the US have not — will hold on to the benefits introduced to counter Covid-19 once a return to profit moves into focus.

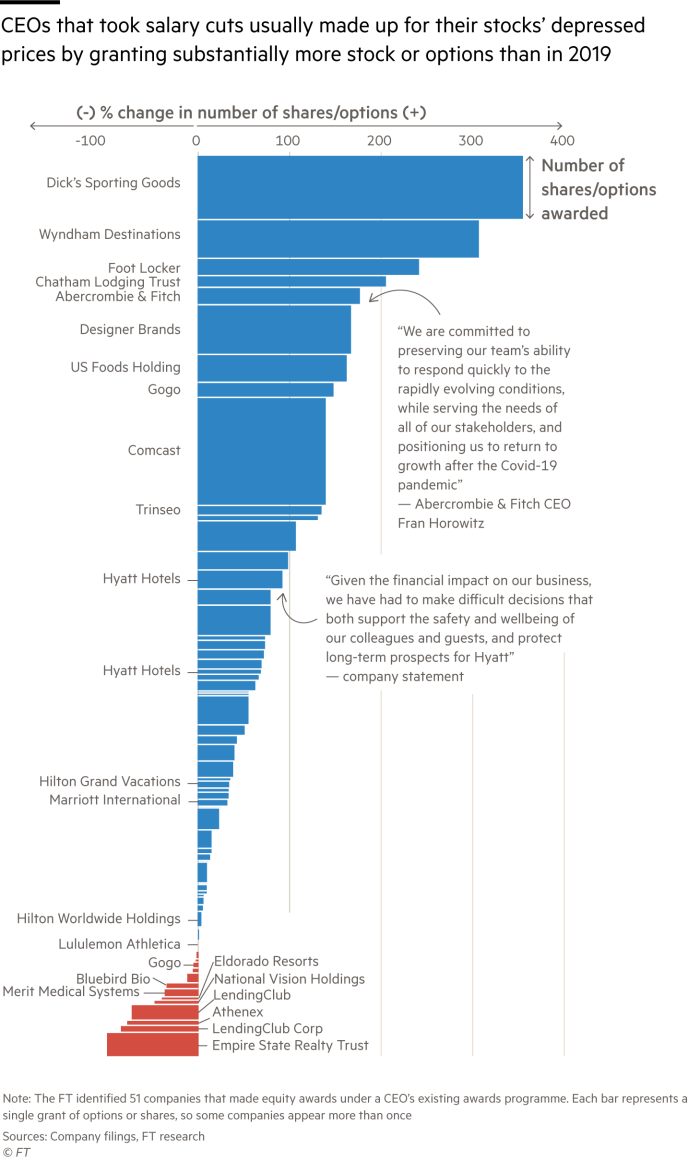

• Executive Pay

At the other end of the worker spectrum is top-level management. One-tenth of respondents to the Future Forum think-tank survey said their companies had cut senior executives’ pay. Kimberley Lewis, engagement director at Federated Hermes, was encouraged by how companies had responded to the virus “with one exception — CEO pay”. A survey in mid-April by Semler Brossy, the pay consultant, found that the few companies that had cut executive pay had acted out of necessity: most had adopted a wait-and-see approach.

After the virus: The pandemic is as unlikely as the financial crisis to bring about a long-term reduction in executive pay. Research by the Economic Policy Institute shows that in the US, chief executive remuneration at the top 350 companies rose by more than half between 2009 and 2018 (this counts options as exercised; the proportion drops to 29 per cent if only options as granted are counted). At the same time, wages for the typical worker in a large firm grew by just 5 per cent. The top 100 companies in the UK have been more restrained, perhaps because of stronger legislation. Total chief executive compensation has been flat since 2010, according to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. Government intervention does make a difference. For example, governments can decide to convert debt to equity and take more of an interest in their holdings. An even more effective approach would be industry-wide legislation, such as that which has affected UK pay scales. Share incentive schemes also warrant scrutiny. Joel Bakan, professor of law at the University of British Columbia and author of the forthcoming book The New Corporation: How “Good” Corporations are Bad for Democracy, links the inability of companies to “weather the storm” of Covid to the unfettered power of top management to use “debt and record profits to buy back shares and boost their stock option pay”.

-----

Environment

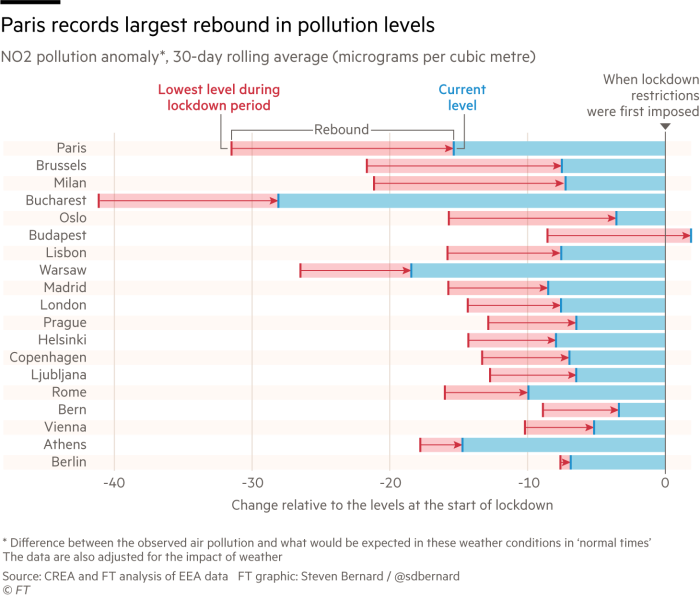

• Emissions have declined, if only due to inaction

Environmental issues have largely given way to social concerns during the pandemic but the economic shutdown did lead to less pollution and better air quality. The International Energy Agency has predicted that the Covid-19 crisis will lead to an 8 per cent drop in CO2 emissions by the end of 2020.

After the virus: The inactivity will not last and progress made in emissions reduction will be only short-term. On the plus side, business trips could reduce because so many more people have become familiar with video conferencing. Consumer behaviour also needs to drive corporate change. As with the faraway textile worker, the environment is not a sufficiently visible issue for most consumers to make the choices to protect it, for instance by paying a price for a T-shirt that covers the cost of the 2,700 litres of water which, according to the World Wide Fund for Nature, go into its manufacture. As one Future Forum participant said: “We’ve seen that the whole world can change rapidly, so if we want to arrest climate change it is possible if [there is] collective will from governments, business and citizens”. Here, governments have begun to step up. In June, Germany delivered a boost to green policies by directing bailout funds towards industries that could help to reduce emissions.

-----

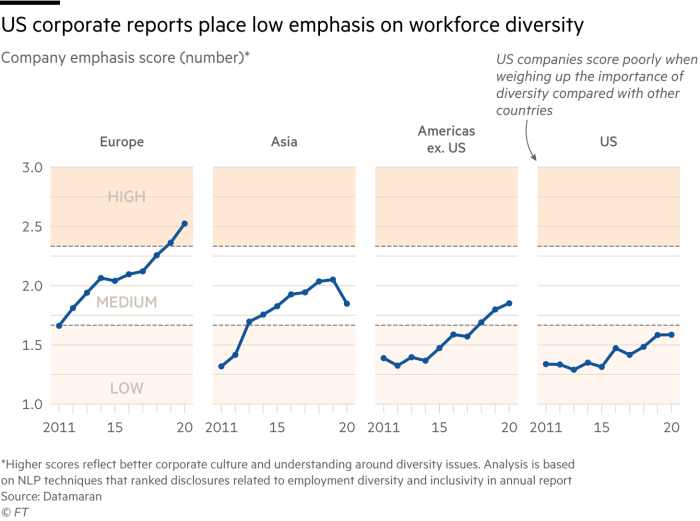

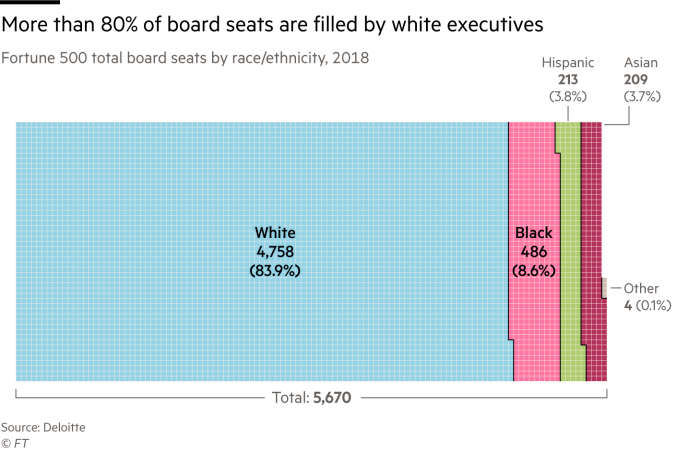

Diversity

• Out of the spotlight — until the death of George Floyd

As disruption caused by the coronavirus spread, diversity issues took a back seat. Ms Lewis of Federated Hermes said, however, that the events surrounding the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May “have raised a lot of issues relevant to companies and their stakeholders”. There is now an urgent need to examine corporate cultures in areas from executive diversity and pay gaps to promotion rates and exit ratios for people of colour. Gender diversity, she noted, had always been an easier issue for companies to tackle — even if it has required legislation for companies to take action, as in California, for instance.

After the virus: The pandemic has undoubtedly increased public sensitivity to social injustice and companies have read this change in mood. More business leaders have made statements condemning Mr Floyd’s death, expressing solidarity and vowing to examine their diversity practices. Ms Lewis pointed out that “there is often a disconnect between the companies’ statements and what we might actually find when speaking to the employees”. However, she was optimistic that things could change. “If anything positive comes of this it will be a wake-up call that this is not something to bury in a vague statement . . . it is something that is impacting your business and your people, and you have to address it.”

-----

Conclusion

The obstacles to change are considerable and executives are sceptical that improvements in corporate behaviour will be long-lasting.

One-third of the FT Future Forum participants said “businesses won’t change” in the wake of the pandemic. Two-fifths of respondents to a reader survey admitted that there were barriers in their own companies to adopting responsible business practices, including “lack of understanding”, “cost implications” and a “potential negative impact on profitability”.

Many expressed a hope that things would change but had little conviction. One reader observed that “ultimately, the psychology of business is led through its leaders’ personalities, and those don’t easily change”.

Those in a position to push for change are more optimistic. Executives in fund management continue to engage companies on worker benefits, health and safety and the environment. They believe that the momentum to enhance corporate responsibility can be sustained.

Even as employee welfare appeared to be taking precedence, support for climate change shareholder resolutions jumped to 23 per cent to May 20, an increase of some 7 percentage points on 2019, according to data compiled for FTfm, the FT’s fund management section.

In an ideal world, companies would use the pandemic as a chance to radically rethink behaviour and, as Prof Mayer hoped, rediscover the sense of purpose that has been trampled upon in the pursuit of profit. This may not happen without a change in the law, Prof Mayer acknowledged. He believed that the best route would be to change corporate law and make directors responsible for delivering a company’s purpose.

Prof Bakan believed the critical question was not whether companies would change their behaviour but how governments could compel them to do so. For the corporate, he says, “the social and environmental quest will always be tailored to create shareholder value . . . even if you tweak companies’ legal mandates that is still the case. With regulation, on the other hand, the government can say: ‘We determine the balance between profit and social values. We are telling you that you are not allowed to hire children under 16.’ There is no management or board discretion on this.”

“In all these crises,” Prof Bakan added, “we have asked: how can corporations solve them?

What we really need to be asking is: how can governments solve these crises by restraining what corporations do?”

Comments