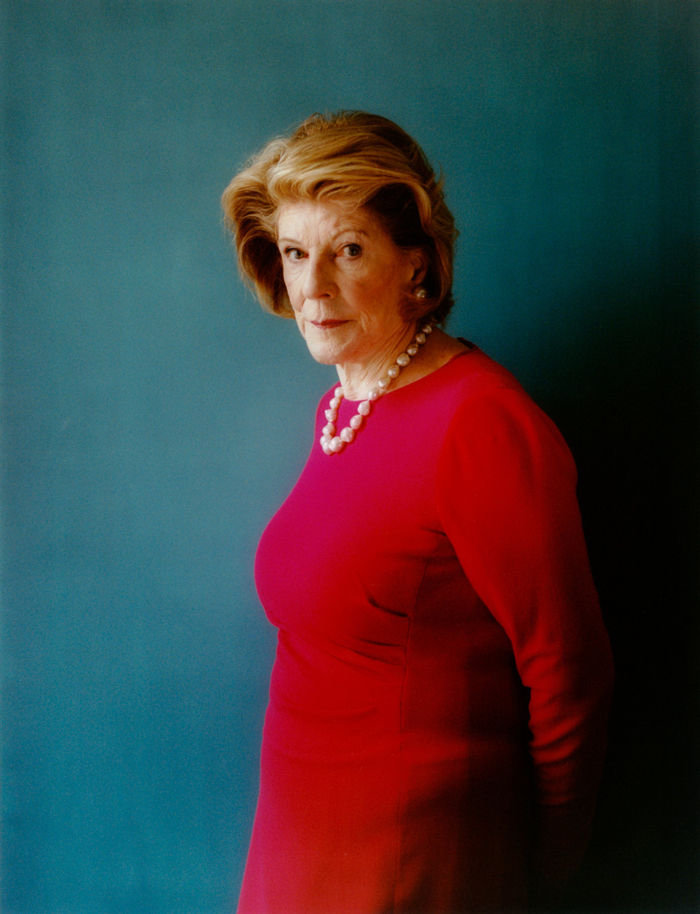

Call me Aggie: the legendary collector making a difference

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It is not often that one gets to talk to a legend in their lifetime. So I was rather overawed when, one bleak January evening, I called Agnes Gund in New York.

“Call me Aggie, everyone does!” she said immediately — typical of her open, almost diffident manner. Yet few art collectors have such formidable reputations. President of MoMA in the 1990s, and current chairperson of MoMA PS1, Gund is a patron and philanthropist as well as a collector. She has served on many boards, from the Cleveland Museum of Art to the National YoungArts Foundation; she’s also an honorary member of London’s Royal Academy. In the 1970s, she set up Studio in a School, a programme to bring professional artists into schools to give classes and help teachers. It has reached 850,000 students to date in New York City and beyond.

Now 81, Gund started collecting art when she was young. Her father was president of the Cleveland Trust Company, then one of the largest banks in the US. He filled their home with pictures by American Western artists such as Frederic Remington, as well as by the Spanish artist Joaquín Sorolla. Her father’s collecting was an important influence on Gund — as were the regular trips to the Cleveland Museum of Art with her mother.

When her father died in 1966, Gund decided to use her inheritance and start buying art. Her first purchase was of a Henry Moore sculpture. In 1967, aged 29, she joined the International Council of MoMA in New York, with the encouragement of art collectors including Emily Tremaine, Ginny Wright and Katherine White.

Gund first saw the work of Mark Rothko on Tremaine’s walls, and bought a key piece from the artist’s studio. She now has outstanding holdings of works by Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly and Mark Rothko, James Rosenquist, Joseph Cornell, as well as more contemporary names, including Christo and Rachel Whiteread. The collection numbers some 1,000 works in all, and also features pieces by Brice Marden, Donald Judd, Arshile Gorky, Sol LeWitt, Joseph Beuys and Tony Smith, to name a few.

Two years ago, Gund surprised the art market when she sold one of her most valuable possessions, Roy Lichtenstein’s 1962 “Masterpiece”, to the billionaire investor Steve Cohen for $165m. Her plan was, if anything, even more surprising: she used $100m from that sale to set up the Art for Justice Fund, along with the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors.

“The fund is an important thing,” says Gund now. She was moved to set it up after seeing 13th, Ava DuVerna’s 2016 documentary about the injustices of the US prison system, particularly for African American people. “They stay in prison because they don’t have enough money to pay bail, as well as all the other things that have put them in jail,” she says. As well as her life-long commitment to social justice, she has a personal reason for seeding the fund: half of her 12 grandchildren identify as black or brown.

The fund’s goals include bail reform and supporting re-entry into society after release. It also supports artistic projects calling attention to racism and injustice in the prison system, and funds art programmes for prisoners. The playwright and performer Liza Jessie Peterson received $100,000 to stage her one-woman show about the criminal justice system, The Peculiar Patriot.

In addition, the fund has supported ending the requirement that bail is paid in cash in California and New York, and was involved in the decision to close Riker’s Island, the notorious New York penitentiary that has seen shocking cases of neglect and suicide. Last October, New York’s lawmakers announced that it will be shuttered by 2026.

Support for the fund is gathering steam. At last year’s Frieze LA, the artist Mark Bradford donated the proceeds of the sales of his print “Life Size”; its 45 editions each sold for $25,000, and he gave $1m in total to the fund.

I ask Gund how she chose to sell the Lichtenstein from all her treasures. “The reason was simply because I didn’t have that much left to sell!” she replies. “Most of my collection is already given, or promised, to about nine museums after I die. They include my Jasper Johns’s ‘Map’ — which I still have in my house, along with others, including the Twombly, the Rothko [‘Two Greens and a Red Stripe’ (1964)] and the Cornell box [‘Medici Princess’ (1948)]. I chose the Lichtenstein because I knew I could get a lot for it; Steve Cohen had been trying to buy it for years.”

Gund is modest about her own impact on the fund. “I don’t think I’ve been very successful in persuading others — I am not a good fundraiser; I think my daughter [Catherine] would be better at that. And it takes time to convince people, but the Ford Foundation has done a great deal in supporting it. We will see a lot more help, I hope, in the future.”

In terms of donations, she hopes that “a little something more” will come in when the documentary film Aggie, which chronicles her life and career, is released this year. It was directed and produced by her daughter Catherine and premiered at Sundance in January.

I ask Gund how she built up her collection, and whether her choices were based on instinct or were more intellectual. She studied history of art for her MA at Harvard, and says with the same diffidence: “I always wanted to be a curator. After college I had to convince myself I could actually do it, but I didn’t go beyond my Master’s. That was as far as I went.”

But she continues: “If I could, I would have collected Old Master drawings, Rembrandt, and so on. But I knew you had to keep them in the dark and I like light! I like Old Master drawings better than contemporary art, really. But contemporary art was what I could have — and I knew it didn’t belong under wraps where people couldn’t see it. So, I became interested in selecting contemporary.” Now she collects mainly for museums, so it’s “what they want rather than what I would want.”

As for the fund, it has a finite lifespan. In theory, it will wind up in five years’ time. “The Rockefeller Foundation, the Kellogg Foundation and others, they keep back a certain amount so that when stocks go down they still have money,” Gund explains. “They perpetuate themselves for ages this way, but we didn’t want to do that, we wanted to be able to gift for the needs of now.”

The fund seems to be carrying out well — it has already made more than $43m in grants to over 100 projects and activists. So its effects should live on beyond its five-year lifetime.

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our culture podcast, Culture Call, where editors Gris and Lilah dig into the trends shaping life in the 2020s, interview the people breaking new ground and bring you behind the scenes of FT Life & Arts journalism. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Comments