Second-hand fashion gets the big tech makeover

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For decades, consumers have rummaged through rails at flea markets or charity shops, in search of vintage gems or just a bargain.

But the sale of second-hand clothing has been catapulted into a digital age of rapid growth, dealmaking and sky-high valuations.

The most recent example of the surge of investor interest in resale platforms was last week’s $1.6bn takeover of second-hand fashion app Depop by Etsy.

But 2021 has also seen ThredUp and Poshmark list in the US and Gucci owner Kering take a 5 per cent stake in Vestiaire Collective, the upmarket France-based resale platform. Vinted, a European resale site, tripled its valuation in a funding round last month.

The most important driver of the resale trend is technology, which has transformed what was often a serendipitous treasure hunt into an Amazon-style “endless aisle”.

“You need to be able to find what you want in your size and in physical retail that is always going to be a challenge,” said Maximilian Bittner, chief executive of Vestiaire Collective, which facilitates trade in mid to high-end pre-owned clothing in about 70 countries.

He also pointed to growing concerns, especially among younger consumers, about sustainability and the environmental impact of fast fashion. Giving an item a new lease of life “you literally feel like an eco-warrior tying yourself to the tree”.

Another growth driver is the Covid-19 pandemic: wardrobe clear-outs across the globe fuelled sales while extended periods of shop closures in many countries spurred demand. Revenue at Depop doubled last year, though it is still fairly modest at $70m and investors were disappointed with recent growth at ThredUp and Poshmark.

“As is the case with clothing rental and subscription retail, we don’t yet know which of these operators will scale and which will ultimately make money,” said Jacqueline Windsor, a strategy partner at PwC.

She points out that despite their superficial similarities, they have different business models. Depop is a pure peer-to-peer platform, where sellers and buyers sort everything out between themselves. Vinted works a similar way, but buyers pay commission and a fee for protection in case of non-delivery or faults.

Vendors also do much of the work on Vestiaire but the platform requires authentication on all items advertised for €1,000 or more — a service for which the buyer pays a fixed fee — in an effort to combat fakes.

New York-listed RealReal, which focuses on luxury, is even more hands-on; it writes descriptions and photographs items on behalf of sellers.

As most of the platforms are funded by venture capital, details on financial performance are largely private. But James Wise at Balderton Capital, which is an investor in both Depop and Vestiaire, says they are characterised by high gross margins and powerful operational leverage.

“They don’t have logistics arms, they don’t do delivery. It’s not a business where the margin scales incrementally per dollar [of revenue], it scales exponentially,” he said.

“The reason the best businesses in the space are not yet profitable is mainly marketing. They want to spend on growth . . . the best way to deploy that marginal capital at the moment is going into new markets and getting the offering to more people.”

He expects very large businesses to emerge in individual sectors, pointing to StockX’s dominance of sneaker resale as an example, although Vinted’s chief executive Thomas Plantenga said he intended to offer breadth rather than depth: “We are not focused on a certain sector, we sell all types of clothing.”

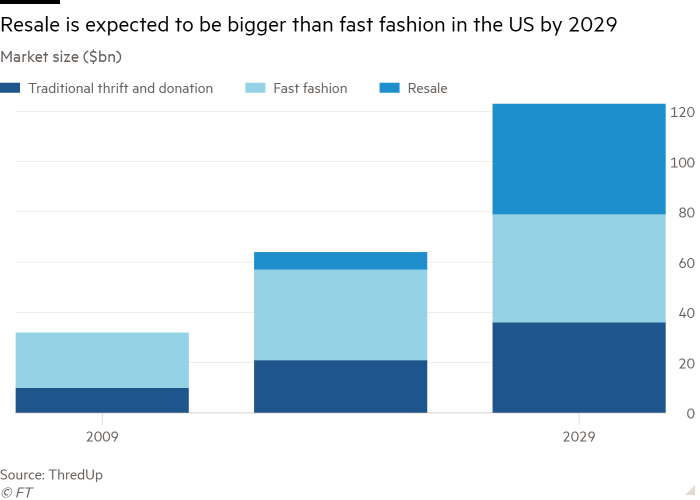

How big the resale sector is, or could ultimately be, is hard to gauge due to the fragmentation and informal nature of many of the transactions.

A recent report for ThredUp by GlobalData forecast that resale in the US would grow 39 per cent a year between 2019 and 2024, to reach $36bn.

German online fashion retailer Zalando recently predicted 15-20 per cent annual growth globally over the coming five years. Its survey found that while three-fifths of consumers believed buying second-hand was a great way to shop sustainably, only a quarter do so.

Traditional operators do not believe that digital upstarts are taking significant share from them. Depop and its ilk “have highlighted how brilliant second-hand can be and the halo effect of that has been good for us”, said Kate Avenelli, head of retail at Save the Children, which runs 120 charity shops across the UK and already works with eBay, Asos and Depop.

Jenny Macdonald, who has run The Magic Wardrobe pre-owned clothing boutique in Essex, in the east of England, for 14 years, is confident her business will continue to lure customers. “People can come in here with £50 and get a whole outfit, it just makes me so chuffed,” she said.

Plantenga said he had no doubt that “where we enter a market we are absolutely growing that market”.

“Second-hand is a very immature market, it is only just starting to grow . . . there will be space for multiple market players in future,” he added.

Windsor at PwC believes second-hand will increasingly encroach on fast fashion turf. “Teens don’t think in terms of resale versus new. They think about what they can get for the amount they have.”

This mindset poses a big challenge for established fashion brands, which will have to either collaborate with platforms, launch their own resale businesses or perish, says Wise. “This is an existential question for some of these brands . . . they are going to be under pressure for a decade to come.”

He adds that while brands such as Levi Strauss and Hennes & Mauritz have entered resale, for many trying to compete “will be like Barnes & Noble launching its own Kindle and trying to de-platform Amazon”.

Bittner says that while “every fashion CEO has thought about this”, they do not have access to the same pool of buyers and sellers as platforms and are increasingly aware that second-hand is a way to introduce new customers.

Vestiaire operates a concession in London’s Selfridges and recently teamed up with Alexander McQueen to allow vendors to sell pre-owned items through its site in return for credit to be used at McQueen boutiques. Depop has resale collaborations with Adidas, Benetton and Ralph Lauren.

“We are educating the consumer to buy items that are more durable and brands can increase customer loyalty by encouraging customers to trade in,” said Bittner.

Additional reporting by Leila Abboud in Paris

Comments