Turbulence fails to dampen Frieze art fairs’ return to London

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

London celebrates the art world’s glitz and glamour at the Frieze fairs, which return to Regent’s Park this coming week. Founded amid the heady optimism of London’s financial boom in 2003, its organisers are hoping that this year’s bleak backdrop — a weakened currency, high inflation and rising interest rates in the shadow of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — doesn’t dampen the mood.

Within the art market, the UK’s status is already shaky, again losing its second spot in the global league table to China last year. Frieze itself has recognised the growing significance of Asia, recently opening its inaugural fair in Seoul, South Korea. Brexit too cannot be ignored: Paris has become attractive to galleries and collectors since the UK’s decision to leave the EU. The talk in London this month centres on the impact of the latest fair from Frieze’s main competitor, Art Basel, which opens in Paris straight after the Regent’s Park tents come down.

“The whole world is in a difficult place right now, not just the UK. But despite the general uncertainty, London is still the most global and most exciting of Europe’s art capitals,” says Eva Langret, director of Frieze London. Originally from Paris, she says of her move to the UK capital in 2005: “I came here for a reason . . . London offers opportunities to build a career without [the luck of] being born into the art world. London gives space to new voices and new communities in a way that I don’t see elsewhere.” She points to recent data from the office of the mayor of London that finds there are more than 300 languages spoken in the UK capital, more than in any other city in the world.

Still, London’s gallerists confess to suffering in the current economic climate. “The concern is that the weakness [of the pound] might limit our capacity to do business internationally,” says Antonia Marsh, the founder of Soft Opening gallery. She accepts that, since Brexit, some European buyers find it attractive to buy works in the UK — saving on VAT if they are then exported — but she says “the increase in shipping costs and administrative fees make everything much more difficult”. For Frieze London, she brings work by Rhea Dillon to the Focus section for emerging talents. Dillon’s project explores the difference between the Caribbean diaspora “landing” and the more self-directed “arriving”. Dillon, a child of immigrants to the UK, now feels able to “arrive”, Marsh says.

But of course, the weakness of the UK’s currency has well-known upsides for the international art trade. “It isn’t something that we openly advertise, but a low pound is good for our international visitors,” Langret says. Similarly, non-UK bidders at next week’s headline auctions will have an advantage over Britons, while the taxis collectors take and the meals they consume will also be cheaper.

Frieze Masters exhibitor Wendi Norris, based in San Francisco, says: “For my US collectors, the strong dollar presents a great time to acquire.” She brings a selection of work by female surrealists — including Leonor Fini, Dorothea Tanning and the gallery’s latest charge, the estate of Eileen Agar. London, Norris says, offers “the most internationally diverse art market with collectors from all corners of the world”. Frieze sponsor VistaJet, a private jet operator, has taken an apartment suite in a John Nash neoclassical townhouse near Regent’s Park to offer a luxurious respite — with facials and massages on request — to its fair-bound members.

Frieze’s list of galleries demonstrates how London still punches above its weight in the commercial art world. Of the 281 major-league exhibitors across both Frieze London and Frieze Masters, more than 110 have a space in London. Many of the artists on show are or were based in London, a city that Langret notes has served them well with its prestigious art schools and museums.

For Thomas Dane Gallery in Frieze London, the Turner prize shortlisted artist Anthea Hamilton has chosen works by 17 artists, including herself. She finds much to celebrate within her selection. “I am really excited by the artists coming through in London. Many had far more compromised MA and BA programmes than I [did], facing exclusive tuition fees, barely any studio space and then making it work in this gentrification-saturated city,” she says. Hamilton identifies “a different kind of capacity to make work that confronts and is in dialogue with what is happening”, highlighting the London-based Rene Matić, Zadie Xa, Ufuoma Essi and Tai Shani — a Turner prizewinner — as artists who are “pushing things forward”.

Today’s market darlings also support London’s status as a contemporary art powerhouse. At Gagosian’s booth, which will greet visitors at the entrance of Frieze London, comes a solo showing of new work by the British superstar painter Jadé Fadojutimi. “She really responded [well] to the idea,” says Millicent Wilner, director of Gagosian. “Frieze works as a platform for a solo show — you can get more people who see the booth in four days than through the run of a [gallery] exhibition.”

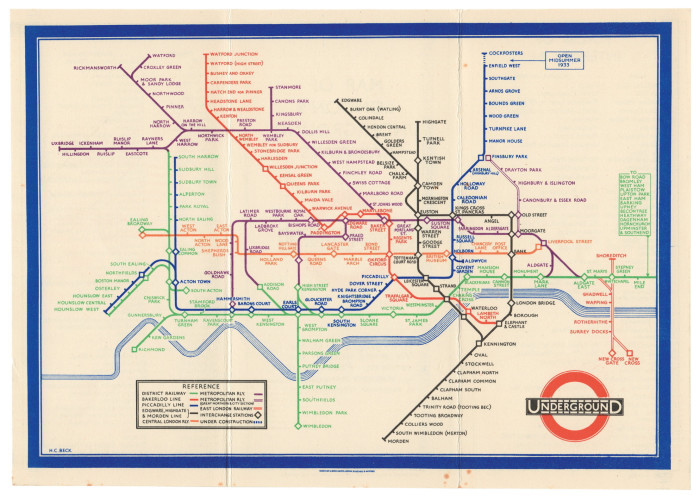

A celebration of London comes to Frieze Masters via Daniel Crouch. He brings highlights from a collection of more than 30,000 books, maps and prints of London amassed for decades by Roger Cline, a patent lawyer. This reminder of London’s history of collecting is now offered as a whole for £2mn. Most of the items date from the 18th and 19th centuries, though the collection spans more than 400 years and includes the earliest extant map of London, made by Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg in 1572, and a 1933 map of the London Underground by Harry Beck.

“It might be a stretch to say that a collection of maps and prints can tell you anything about a whole city, but its breadth and depth tells a story,” says Crouch. “You see how London has been surprisingly slow to grow. Its success didn’t come out of one period of wealth, but from reacting well to trends. London grew up on trade and graft. It is facing challenges right now, but the city has proved resilient over two millennia.”

October 12-16, frieze.com

Comments