Covid crisis likely to mask economic fallout of no-deal Brexit | Free to read

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

With talks between the EU and UK deadlocked, Britain is once again confronted by the prospect of a no-deal Brexit come the end of the year.

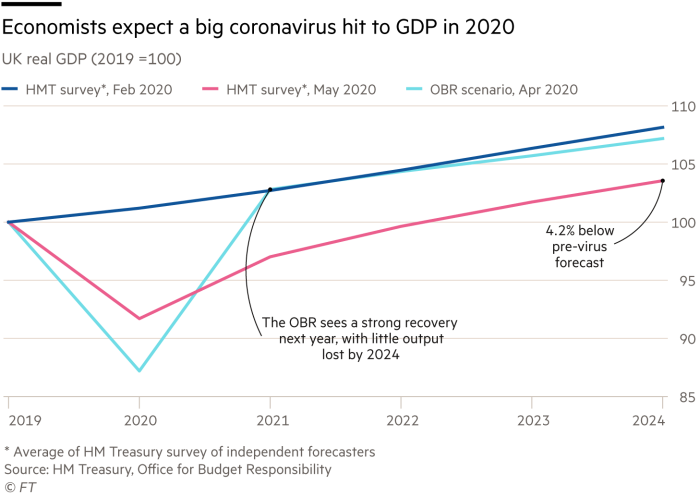

Yet with the UK economy already ravaged by coronavirus, some economists and policymakers in Britain are wondering whether the effects of the UK failing to secure a trade deal with Brussels could be masked by the impact of the pandemic.

“Any costs from a change in our relationship with the EU are likely to be trivial compared to the swings in GDP due to coronavirus, as well as potentially being smaller during the crisis than they would have been otherwise,” said Julian Jessop, fellow at the think-tank the Institute of Economic Affairs.

Warnings about a no deal now are similar to those aired in 2019. Nissan has said that if there were tariffs on UK to EU trade, there could be no guarantees about the future of its Sunderland car plant. Carolyn Fairbairn, head of the CBI employers’ organisation, said that after battling to survive coronavirus, companies had “almost zero” resilience and ability to cope with a chaotic change in EU trading relations. And the new Bank of England governor, Andrew Bailey, has pressed banks to ensure they are adequately prepared.

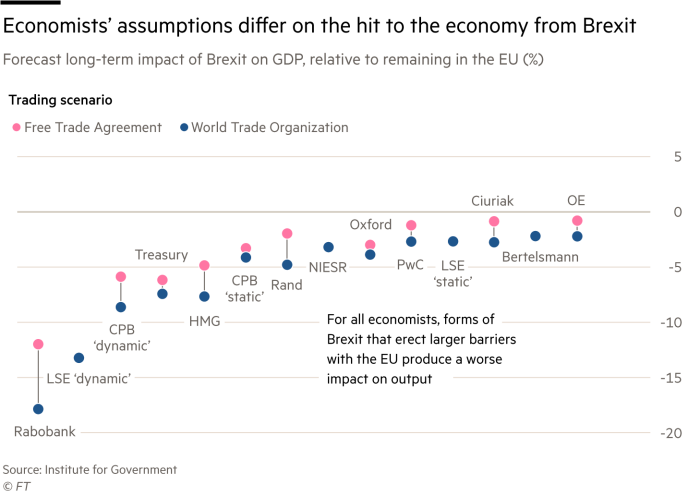

At worst, the British government’s 2018 analysis expected a no-deal Brexit to lower the output of the UK economy by 8 per cent over a 15-year period compared with remaining in the EU. The Office for Budget Responsibility has forecast that coronavirus will deliver a 13.8 per cent hit to gross domestic product this year alone.

It is not only the scale of the Covid-19 crisis that lowers the risk of a no-deal Brexit, according to those who want Britain to take a tough stance in negotiations with Brussels, the latest round of which are due to finish on Friday.

They argue the immediate crisis could ease the pain of dealing with some of the side-effects from a harder exit from the EU’s single market and customs union, which Britain currently retains access to through the Brexit deal agreed between prime minister Boris Johnson and Brussels last year.

Not only might the reduction in trading flows between the EU and UK owing to coronavirus take the pressure off the channel ports of Dover and Calais in the event of a no deal, but high unemployment may mean more people are keen to join the small army of 50,000 customs agents needed to ensure the smooth operation of new border regulations.

Cabinet office minister Michael Gove has gone the furthest in public in making the case that the “reshoring” of domestic business operations that might be needed to build resilience against future pandemics is just the sort of adjustment required to deal with higher barriers to trade with the EU. “It is impossible to state precisely, but the shape of the UK economy, like the shape of member states’ economies in the EU, is going to change,” he told MPs last month.

The problem with all of these arguments, according to a still large majority of economists, is that even if coronavirus is a bigger economic problem, why should government compound its difficulties with unnecessary further pain.

With many economists predicting social distancing will lead to long-term damage to the economy, the additional hit of higher trade barriers and potential disruption at ports from a no-deal Brexit — with higher quotas and tariffs — will heighten the economic challenges facing chancellor Rishi Sunak and the Treasury.

Kallum Pickering, UK economist at Berenberg Bank, said that even though Covid-19 might disguise the impact of no deal, it would not eliminate it. At worst, he said, the economy could even be tipped back into recession at the start of 2021.

“A collapse in talks followed by a hard, unmanaged exit would hurt confidence, spending and investment,” Mr Pickering said. “The UK would likely suffer a comparatively slower recovery from the pandemic recession than other major European economies.”

Alan Winters, head of the Trade Policy Observatory at Sussex University, said companies were in no position to make the adjustments they would need to reorient themselves and reshore because so many were now loaded up with debt, taken on to help weather the Covid-19 storm.

Unlike those who say it is an opportune moment to take risks, he warns that the fragility of company balance sheets “will make the already difficult job of adjusting to Brexit more difficult”.

And after a study of the connections of the UK service sector with international customers, David Owen, chief European economist at Jefferies, the investment bank, said reshoring across Europe was likely to lead to a concentration of activity inside the eurozone.

For the UK, he said, “much depends on the access it still has to the European markets for its key service sectors after the transitional phase has come to an end”. That would depend on getting a deal with the EU.

Such concerns may lead the UK government to seek a deal with the EU in the autumn when tensions begin to mount, just as Mr Johnson agreed to erect a customs border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland to break a deadlock in the negotiations last year.

Brexit is far from the government’s largest economic challenge at the moment and experts think the government and the EU will probably find a way to minimise, but not eliminate, the economic costs.

Anand Menon, director of the UK in a changing Europe project, said: “Trade between the UK and EU is going to be more difficult after Brexit. How much more difficult depends on what can be agreed.”

Comments