India’s shadow banking crisis sparks credit crunch

Simply sign up to the Indian business & finance myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In his noisy workshop off a dirt road, Rajaram Yadav uses lathes and other tools to craft stainless steel pipes and parts for use in India’s chemical factories.

The machinist, who works alongside three employees in his cramped shop, dreams of expanding his business. But, like countless other small business owners, he fears a crisis in India’s shadow banking system will leave him unable to secure new funding.

“I’m worried about my business,” said Mr Yadav.

Things had been looking up for him two years ago when he secured two loans from Kinara Capital, one of India’s many so-called nonbank financial companies. But the sector is facing a crunch, with lending from nonbank financial companies falling 30 per cent in the year to the end of March, according to India’s Finance Industry Development Council.

With mounting debts at some large NBFCs, economists now expect some to go bust and put India’s financial system at risk. “This is a crisis waiting to happen,” said Vivek Dehejia, an economist at Carleton University in Canada.

The rise over the past decade of nimble lenders such as Kinara has played a crucial role in India’s recent economic growth. They have provided modest loans to millions of small businesses and consumers who would otherwise have had no access to credit. These nonbank financiers had come to account for a fifth of all new credit. They numbered about 10,000 as of March, according to the central bank.

But last September, a default from infrastructure financier IL&FS, one of the largest nonbank lenders, sent shockwaves through the economy and prompted scrutiny of the precarious loan books of many other NBFCs. The banks and mutual funds that had become key sources of capital for the sector promptly turned off the credit tap.

Kinara and NBFCs that specialise in small personal loans argue their industry has been tainted by a handful of risky lenders who had secured funding from short-term sources such as mutual funds and lent to long-term projects such as luxury real estate development.

“It obviously created a major shock to the system,” said Hardika Shah, Kinara Capital’s founder. Kinara specialises in loaning small businesses a few hundred thousand rupees at a time and has lent a total of about Rs12bn ($174m). “The first reaction was one of uncertainty, panic. Everything froze up.”

At a branch of a nonbank lender in a dilapidated central Mumbai office, manager Supriya Joshi said fewer customers have been getting loans since IL&FS’s default. On a recent afternoon a couple of dozen employees sat at desks stacked with paper files but only a trickle of customers walked in.

“Last year business slowed down,” she said. “We have to be very vigilant.”

India’s gross domestic product growth has slowed to the lowest level in five years, falling to 5.8 per cent in the first quarter of 2019, from 6.6 per cent in the final quarter of 2018.

“In a way, some of the most visible elements of India’s economic prosperity over the last 20 years — the auto sector, real estate sector and consumer durables sector — are under threat as the mode of financing for these sectors comes under pressure,” said Saurabh Mukherjea, founder of Marcellus Investment Managers.

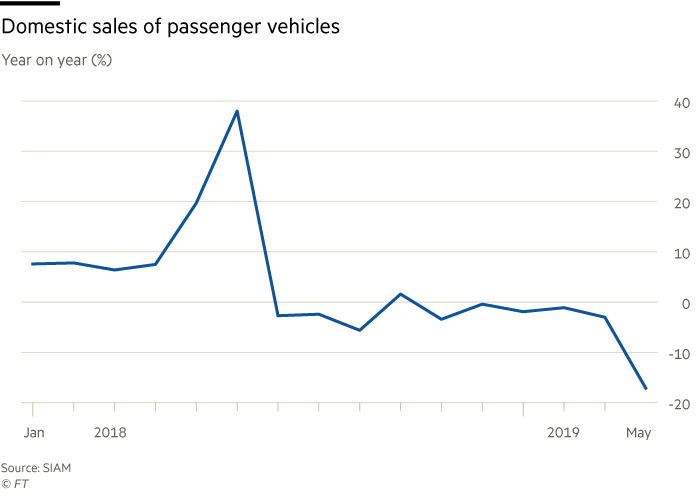

Passenger vehicle sales, buoyant in India’s boom times, dropped 17.7 per cent in April, the largest fall in almost eight years. About 40 per cent of new vehicle loans came from nonbank financiers, according to Capital Economics.

“We are choking our economy of credit,” Sanjiv Bajaj, chief executive of Bajaj Finserv, which runs one of India’s largest nonbank lenders, said of the subsequent squeeze on the sector.

Authorities have taken a number of steps to prevent a hard landing, with the central bank last month cutting interest rates to a nine-year low.

Some business leaders have called for the government to take over struggling NBFCs, while others want Delhi to include in its next budget, due on Friday, measures injecting liquidity into the struggling system.

NBFCs argue that banks alone cannot satisfy the appetite of the millions of Indians hungry for credit. “It’s a very large market which was underpenetrated,” said Prabodh Agrawal, chief financial officer at IIFL, a financial group with its own NBFC.

Additional reporting by Andrea Rodrigues in Mumbai

Car dealerships feel the freeze

Hundreds of car dealerships have closed in India’s major cities as trouble in the country’s nonbank financial company sector sparks an economic crunch, writes Benjamin Parkin in Mumbai.

Almost 300 outlets have shut in the past 18 months, the country’s automobile dealer association said, the first time the industry has experienced such a wave of closures. The pressure has been particularly acute in India’s largest cities Mumbai and Delhi, where costs are higher.

Car dealers said the rate of closures accelerated after September, when nonbank financier IL&FS’s shock default prompted a liquidity squeeze. Many car dealers relied on nonbank credit to buy vehicles from manufacturers, while customers also typically financed purchases with loans from the sector. About 40 per cent of new vehicle loans came from nonbank lenders, according to Capital Economics.

An unexpected drop in passenger vehicle sales in April, the largest in almost eight years, prompted a scare across the auto industry.

“NBFCs play a major, major role. That’s where our growth comes from,” said Ashish Kale, a car dealer based in Nagpur and president of the association. “Overall viability has gone down in the business, which used to be very lucrative.”

Mumbai-based dealer Amar Sheth, who sells Honda, Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen vehicles, has had to shrink a number of his 15 outlets as a result of the financial pressure.

Mr Kale and Mr Sheth said many dealers had expanded too fast, betting that India’s growing economy would reliably fuel demand for cars.

“It’s anyone’s bet how long it’ll take for the demand to kick in. Those who were very highly leveraged were the first ones to shut,” said Mr Sheth. “The need of the hour is to be more prudent.”

Letter in response to this article:

Crisis gives India the chance to clean up its shadow banking sector / From Kavaljit Singh, Director, Madhyam, New Delhi, India

Comments