Omicron: What we know about Covid strain prompting fresh global restrictions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Just weeks after scientists in South Africa and Botswana first alerted the world to the emergence of a worrying new coronavirus variant, researchers are beginning to understand the implication of its mutations, which far exceed the number on any previous variant.

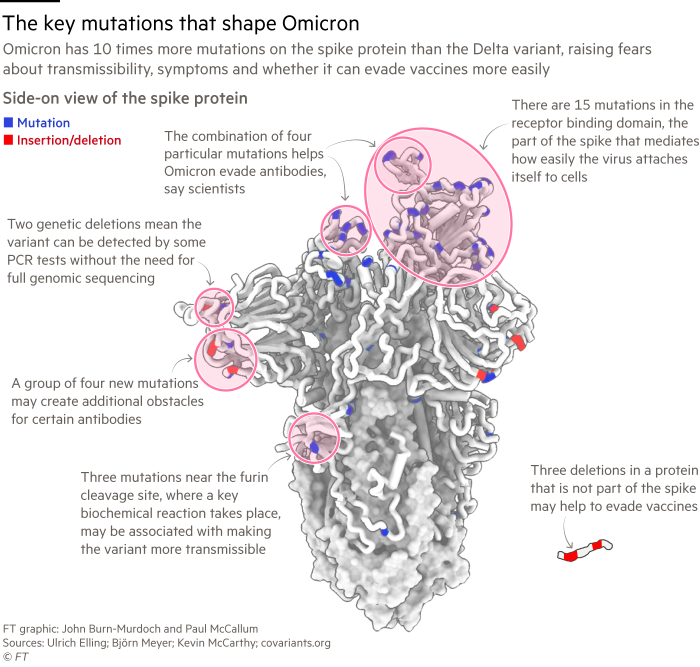

Omicron’s 50 genetic changes include more than 30 on the spike protein, the exposed part of the virus that binds with human cells. Scientists expect these changes to make it more transmissible than the dominant Delta variant and more likely to evade the immune protection provided by vaccines or previous infection.

Why are scientists alarmed about Omicron?

Initial fears were fuelled by Omicron’s highly unusual genetic profile. Jeffrey Barrett, director of the Covid-19 Genomics Initiative at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, described it as “an unprecedented sampling” of mutations from four earlier variants of concern: Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta, together with other changes never seen before whose significance is still unclear.

Fifteen of the mutations are on the receptor binding domain that acts like a “grappling hook” for the virus to enter human cells, said Jacob Glanville, a computational immunologist and founder of Centivax, a US therapeutics company.

Such extensive mutations make it harder for the human immune system, trained by vaccination or previous infection to recognise a different variant, to tackle Omicron. Current vaccines are based on the original strain first detected in the Chinese city of Wuhan two years ago.

Some of the mutations also increase transmissibility regardless of immunity. “From the perspective of evolution, Omicron is the most dramatic evidence of natural selection I’ve ever seen in any organism,” said Barrett.

How fast is Omicron spreading?

Though Omicron was first detected in samples from southern Africa, no one knows for sure where it originated and how it accumulated so many changes.

South Africa was the first country to report a fourth wave of Covid driven by Omicron, starting in Gauteng province, which includes the cities of Johannesburg and Pretoria, and then spreading nationwide. But cases in Gauteng seem to have peaked last week and are now declining.

Elsewhere, Omicron cases are multiplying fast across the world, with numbers doubling within as little as two days in some places and governments responding with measures to restrict social mixing. The UK and Denmark have reported the fastest Omicron growth in Europe, though this is partly a result of their having more thorough genomic surveillance systems than other countries.

The UK Health Security Agency on Monday reported 8,044 confirmed and 25,534 probable Omicron cases, bringing the confirmed and probable total above 170,000. Fourteen people with Omicron infection have died and 129 have been hospitalised in the UK.

How well will Covid vaccines work against Omicron?

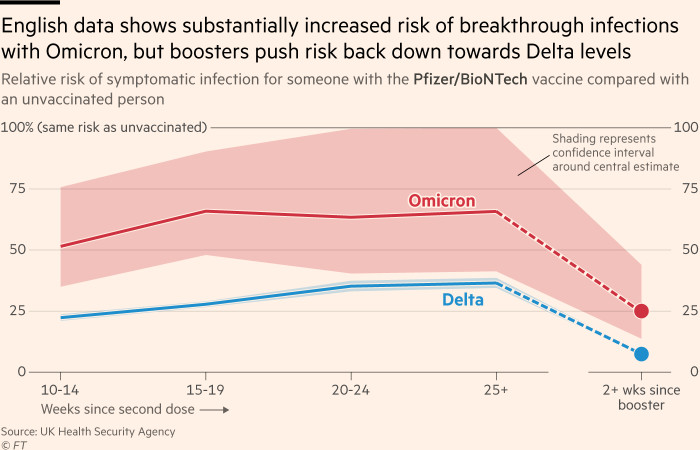

Two lines of evidence are confirming virologists’ fears that vaccines and prior infection will be less effective at preventing cases of Omicron than previous variants. One comes from lab experiments in which scientists expose blood samples to the virus and measure the antibody response. The other uses “real world” epidemiology to estimate how vaccination status affects the risk of developing Covid.

Early conclusions suggest that a large decline in immunity against Omicron occurs after two vaccine doses, particularly among people double-jabbed with the Oxford-AstraZeneca product, while a booster jab works well at restoring most, though not all, of the protection.

On Monday, Moderna said a booster shot of its mRNA vaccine increased antibody levels 37-fold if a half dose was injected and 83-fold for a full dose. BioNTech and Pfizer had previously said a third dose of their vaccine achieved a 25-fold antibody boost, though the studies are not directly comparable.

But lab studies focus on neutralising antibodies rather than the longer-term immunity given by T-cells, which can “remember” past infections and kill pathogens if they reappear. And the Omicron wave has not been going long enough for epidemiologists reliably to estimate efficacy against hospitalisation and death, which is expected to be much higher than against mild breakthrough infections.

How does the disease caused by Omicron compare with previous variants?

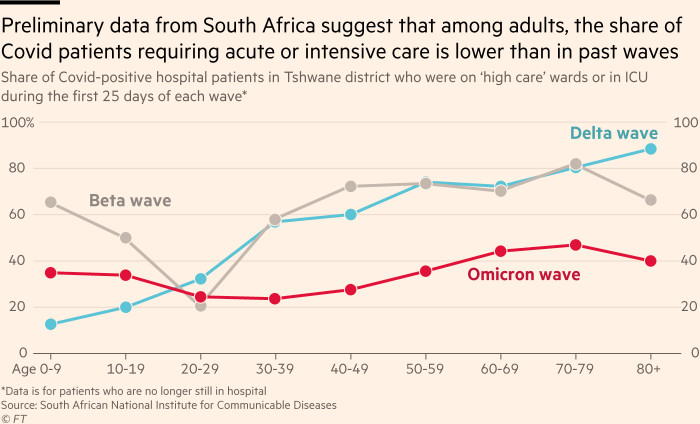

Early signs from South Africa have been encouraging, as people infected with Omicron seemed to show milder symptoms than those in Delta patients. Many were asymptomatic. Others suffered from coughs, fatigue and aches.

However, scientists warn that it is still hard to make direct comparisons between Omicron and previous variants, not only because of the time lag before severe symptoms appear but also because coronavirus immunity in the population through previous infection and vaccination is different today.

Epidemiologists at Imperial College London on Friday published a study of cases in England which, they said, “finds no evidence of Omicron having lower severity than Delta, judged by either the proportion of people testing positive who report symptoms, or by the proportion of cases seeking hospital care after infection”. However, they added, “hospitalisation data remains very limited at this time”.

Laboratory experiments are beginning to illustrate Omicron’s distinctive pattern of activity across different human cell types, which affects disease symptoms. Studies at the universities of Hong Kong and Cambridge suggest that it is significantly less efficient than other coronavirus strains at infecting lung cells and tissue, while it propagates much faster in bronchi higher up the respiratory system. These differences, if confirmed, would help to explain Omicron’s greater ability to pass between people while apparently causing less severe Covid disease.

“Even with the strong booster campaign, Omicron has to be very significantly less severe than Delta to not likely overwhelm healthcare capacity levels,” said Ewan Birney, deputy director-general of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory. “Data from South Africa is interesting and positive about some lower severity of Omicron, but not obviously clear cut that it is at the levels needed.”

Comments