Caring for a growing world means halting mother and child deaths

Simply sign up to the World myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Jorge Odón, an Argentine car mechanic with a talent for invention, woke up in the middle of the night in 2006 with an idea. He had recently watched an online video showing how to easily extract a cork from inside an empty wine bottle using an inflated plastic bag. Until then, all of Odón’s patented inventions had been related to mechanics, but it struck him that night that the technique could be adapted to replace forceps-assisted births.

The idea’s potential also intrigued Mario Merialdi, then co-ordinator of human reproduction at the World Health Organisation. In 2008, he was attending a conference in Buenos Aires and granted Odón a 10-minute meeting after an introduction by a mutual friend. “When I saw the device, I never went back in [to the conference],” he recalls.

Eight years later, a partnership to develop and commercialise the Odón device — which incorporates a simple applicator, bag and hand pump and requires almost no specialist knowledge to use — has advanced substantially. Becton Dickinson, a US medical technology company, has pledged $20m to the project, designed to make the device affordable in low and middle income countries. “This is a test case of whether innovation can be taken to scale. It’s really important,” says Gary Cohen, president of global health and development at BD. “If it succeeds, it will stimulate further confidence. If it does not, it will send a very bad, stifling signal.”

Yet it may be at least three years more before the device makes it to market after clinical trials and regulatory approval. “If someone had told me it would take this long, I would have been surprised,” says Odón.

His experience demonstrates the scope for simple innovations that could help to substantially reduce the unnecessarily high instances of maternal and child illness and death around the world. It also highlights the challenges involved in fostering, nurturing and delivering such innovations. Basic products including medical devices, medicines and diagnostics often already exist, but are not made widely available, including many of the low-cost generic medicines on the World Health Organisation’s “essential medicines” list.

Vaccines, including for measles and yellow fever, have enormous potential to prevent infection and death. Yet even those that are available remain underused, as happened during the last pandemic flu outbreak. That is partly a question of cost, but also of governments’ priorities and of capacity to procure, store, distribute and administer them.

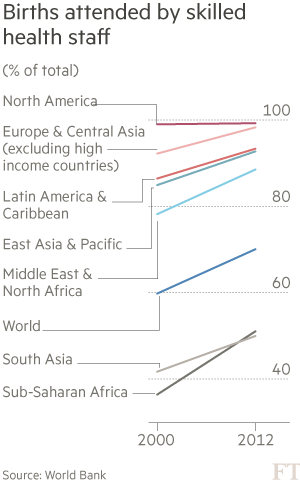

While many health advocates focus their criticism on the high prices that pharmaceuticals charge for medical products — and the intellectual property they retain over them — less attention is paid to the need for more investment in technical aspects of healthcare systems: staffing, training and management.

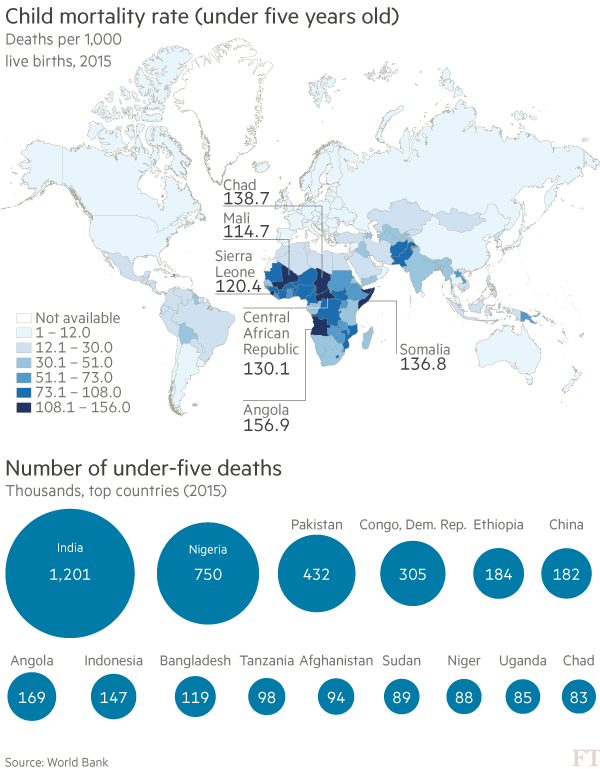

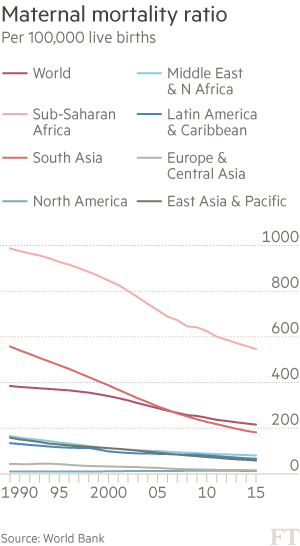

Improving these aspects means holding governments to account. A recent analysis published in The Lancet, the medical journal, estimated that 216 women per 100,000 live births died of maternal causes in 2015 — lower than in 2000, when the Millennium Development Goals were set, but far short of the target numbers set by the MDGs and their replacements, the Sustainable Development Goals.

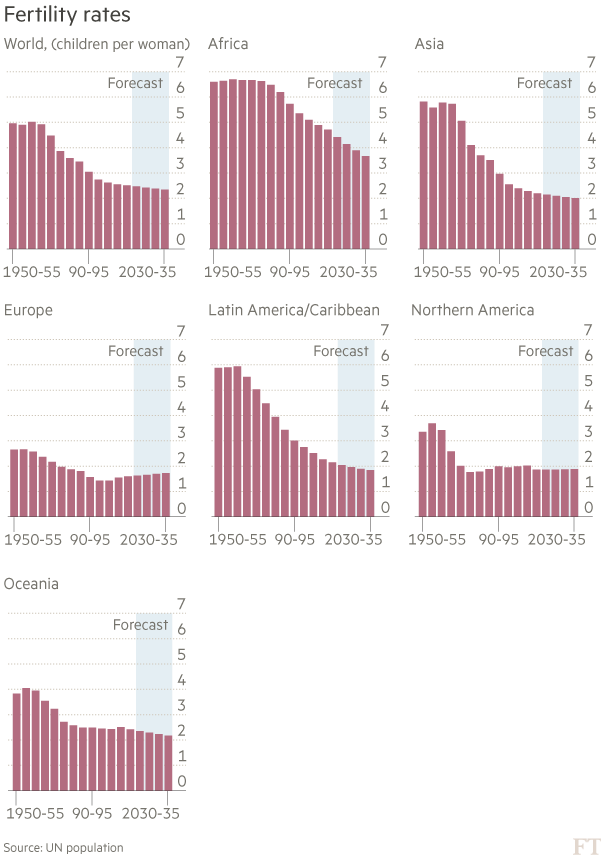

Wider deployment of already available options could make a difference at relatively little cost. For example, the latest estimates suggest that 225m women and girls in developing countries — particularly the poorest and most vulnerable — still have an “unmet need” for modern contraceptives, meaning that they would use them if only they were available.

In turn, improved family planning would reduce the risk of unwanted pregnancies, allowing women to make sure they do not have children too young, too frequently or under circumstances that will impede their own paths to education and employment. Exclusive breastfeeding would do a lot to improve maternal and child health by providing a natural form of contraceptive to space out pregnancies and significantly improving infant nutrition. Medical checklists, popularised by the surgeon and writer Atul Gawande, can ensure procedures are consistent, such as for child birth and prenatal care.

This magazine focuses on the most serious problems facing women and children across the world today, as well as a number of potential solutions: El Salvador’s extremely harsh abortion laws, which often see women imprisoned for aggravated murder; the plight of refugee children across Europe; Chad’s stubbornly high fertility rates and China’s efforts to wean itself off unnecessary caesarean births following the reversal of its one-child policy. It also highlights five examples of innovations that have already demonstrated impact and now need support — whether of funding, expertise or partnership. We invite readers who are interested in helping to sustain, replicate or scale up these projects to contact showcase@ft.com.

Alongside medical commodities such as Odón’s device, these profiles describe simple approaches such as kangaroo mother care, originally developed in Colombia in the 1970s, but now making a difference around the world. Other innovations include the recruitment and training of community health workers to deliver door to door care in Uganda and subsidised health insurance programmes, such as a pioneering project in the western state of Kwara, Nigeria. Its initial success has spurred debate about the introduction of a state-wide programme, allowing richer individuals to support the costs of premiums for the poor.

Kenya has introduced an ambitious multi-year contract that places the onus on manufacturers not only to supply medical equipment, but also to maintain it and train health workers in its use. “Across Africa, there is a junkyard of equipment that is dumped when it goes wrong,” says Nicholas Muraguri, principal secretary at the country’s ministry of health.

Previously, Kenya had just two intensive care units, and a handful of diagnostic and dialysis centres. Patients in remote areas were effectively condemned to die, he argues. The new multi-year contract with five multinational suppliers offers enhanced support across the nation.

But some innovations are condemned to fail because the technology involved is too sophisticated, or because their business model was never sustainable. A number of projects are only carrying on thanks to donors after several years of funding.

The trick is to find the right models and the right partners: whether for-profit and social investors, governments and philanthropic donors; or technical advice and expertise from consultants and companies. Ultimately, they should be effective enough to win the support of the public sector — whether for funding or co-existence.

Babatunde Osotimehin, executive director of the UN Population Fund and a former health minister in Nigeria, stresses the importance of ideas that can be integrated with government plans and that reflect their priorities. Otherwise, they will never be picked up, he says.

Tim Evans, senior director of health, nutrition and population at the World Bank, argues for the need to focus on innovations of significant size to ensure they can have impact and be sustainable. “Small showcase projects are too often unable to get to scale,” he says. “Innovative financing and the ability to implement are essential for real impact.”

Much of the innovation required to ease the ill health of mothers and children is to do with people, systems and funding. As Arnab Ghatak, a senior partner in global public health at McKinsey puts it: “We have a lot of the technology we need. It’s really a question about delivery and engaging with governments.”

Comments