Tick tock star – the artist who made a masterpiece of time

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

If you have ever wondered the height above sea level of the small town of Fairford in Gloucestershire, Jake Sutton has the answer: 307 feet. Or, to be scrupulously precise, that is the height above sea level of his workshop at 10 The High Street, about halfway between the chemist and the bookshop, opposite the church.

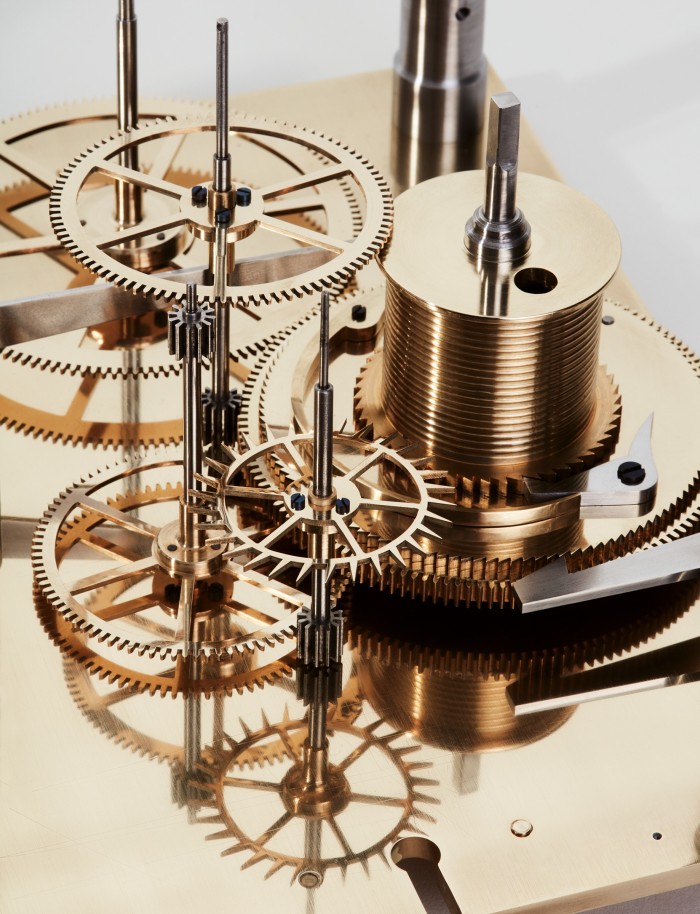

Sutton makes it his business to know such things as, for the past 12 years, at a rate of around two a year, the 73-year-old has been producing longcase regulator clocks (each takes about 800 to 1,000 hours to make). In order to squeeze every fraction of a second of precision out of these handbuilt mechanisms, he makes the necessary adjustments to compensate for barometric pressure and temperature variation so they are accurate to within 10 seconds a year, 0.7 seconds a month, or around 0.023 seconds a day. Just to provide context, Chronometer certification of a wristwatch in Switzerland requires accuracy of within 10 seconds (-4/+6 ) a day.

Clockmaking as practised at this level is a high-wire act, for which meticulous preparation is required. And, as with wire-walking, stability is key. Out of sight behind the hand-engraved dial, the mirror-finished components and the warm glow of the shellac-polished veneer is a solid backplate, a 45mm-thick slab of laminated marine ply and white oak, which in turn is secured with bolts that bore deep into the centuries-old Cotswold stone wall. “I often say to people, watch where you’re putting this; you know it needs a very solid foundation or a masonry wall. There’s no point in expecting accuracy with a stud wall or a sprung floor.”

To demonstrate the delicacy of this work, he has wired up a 30-day pendulum to what looks like a seismograph, measuring the amplitude of the clock to millionths of a second. He opens the glass door and, with a pair of tweezers, deposits a minute weight on a tray halfway up the pendulum, effectively shortening it to make the clock run faster. The weight and the adjustment may be microscopic, but even the slight alteration in the air pressure caused by opening the door sends tsunami‑like waves across the seismograph screen, giving the impression that the San Andreas Fault has just opened up beneath Fairford High Street.

Timing of this order requires precision engineering, and there is an irony that this almost inhuman level of accuracy can be achieved amid the very human clutter of a couple of interconnecting workshops behind a small shop in the Cotswolds, rather than some surgically salubrious, laboratory-like glass-walled Swiss atelier peopled by white-coated watchmakers. More remarkable still is that, until he hit his 60s, Jake Sutton had never made a clock. Instead he worked as an artist. He is probably the only horologist who trained with Gilbert & George, his contemporaries at Saint Martin’s School of Art.

“We used to fight like cat and dog. I mean it was awful: I wasn’t articulate in those days, I couldn’t put my arguments together,” he recalls of his time studying with the then enfants terribles of performance art. At the time, conceptual art and minimalist sculpture of the sort practiced by Carl Andre of firebrick fame was in the ascendant, and Sutton wanted nothing to do with it. “I just didn’t, and still don’t really see an awful lot in it,” he recalls. “I’m a craftsman out of the wrong time. I should have been born at the start of the century, when people wanted painters and pictures.”

Out of step with the rhythm of the times, Sutton was on the verge of leaving St Martin’s when he learned of a drawing class held by a septuagenarian draughtsman who had trained in Paris and known Matisse and Chagall; so for three years, five days a week, he practised figure drawing in chalk, charcoal and pencil. “When it came to my diploma show I was in a tiny corner with black-and-white drawings. Most people didn’t even look.”

On graduation, he settled into the life of a freelance graphic designer: “Cartoons and technical illustrations – I could draw, so it was second nature to me. I was always painting as well.” And it was while he was living in Bath in the early 1970s that he created the Bath Festival poster “using one of my paintings. That was a tremendous success. They had to reprint it three times, which they hadn’t done before. And then a little local gallery rang me up and said, ‘Have you got any more of these?’ I remember taking one in on a Saturday morning, and when I had just got home, about midday, he rang again and asked, ‘Would you like an exhibition?’ An American couple had walked in, and just bought my painting. They started my painting career.”

For the next 40 years Sutton worked as an artist. His work appeared on stamps and on the walls of the Palace of Westminster. He was also commissioned to create a poster for Transport for London (for the Millennium), placing him in the company of Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, and one of his artistic heroes, David Hockney. As an artist, Sutton favoured the sort of subjects that had appealed to Degas: racehorses, dancers, musicians. With his wife, Kim, a dancer whom he had met at school in Manchester in the early 1960s, he set up a gallery in Fairford to sell his works.

“Then, when I was sixtysomething, I did a big exhibition about New York, which was a huge success, but it was very stressful going back and forth to America. When we came back and walked in the door, I suddenly said, ‘I don’t think I want to paint any more.’”

Once some time had passed, Sutton decided to become a clockmaker; not such a leap as it might at first seem. “I was doing precision engineering all the time when I was painting,” he says. Moreover, through a shared love of motorcycles, he had become a friend and disciple of George Daniels, the greatest British watchmaker since the 18th century. “What I learnt from George was his perfection of craftsmanship. That was the benchmark for me.”

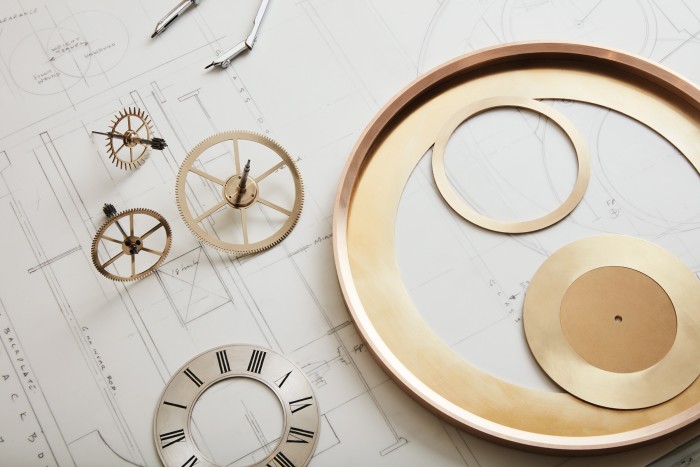

However, as an artist he has one crucial difference with his mentor. “George said there should be no evidence that man has made this clock. I disagree when it comes to engraving. There is a difference between commercial and hand engraving; there’s no soul. It’s the slight imperfections that attract our eyes.”

In that respect, he sees no difference between a clock and a charcoal drawing. “I differ from clockmakers in that I see it as a work of art and therefore I have to make every part myself.” From the veneer for the case to the hardened-steel pallet of the deadbeat escapement; from the tiny catch that gently opens the glass front of the door to permit winding and setting to the elegant blued steel fingers (Sutton prefers to use the 17th- and 18th-century term for hands) that circumambulate the dial – he is responsible for it all.

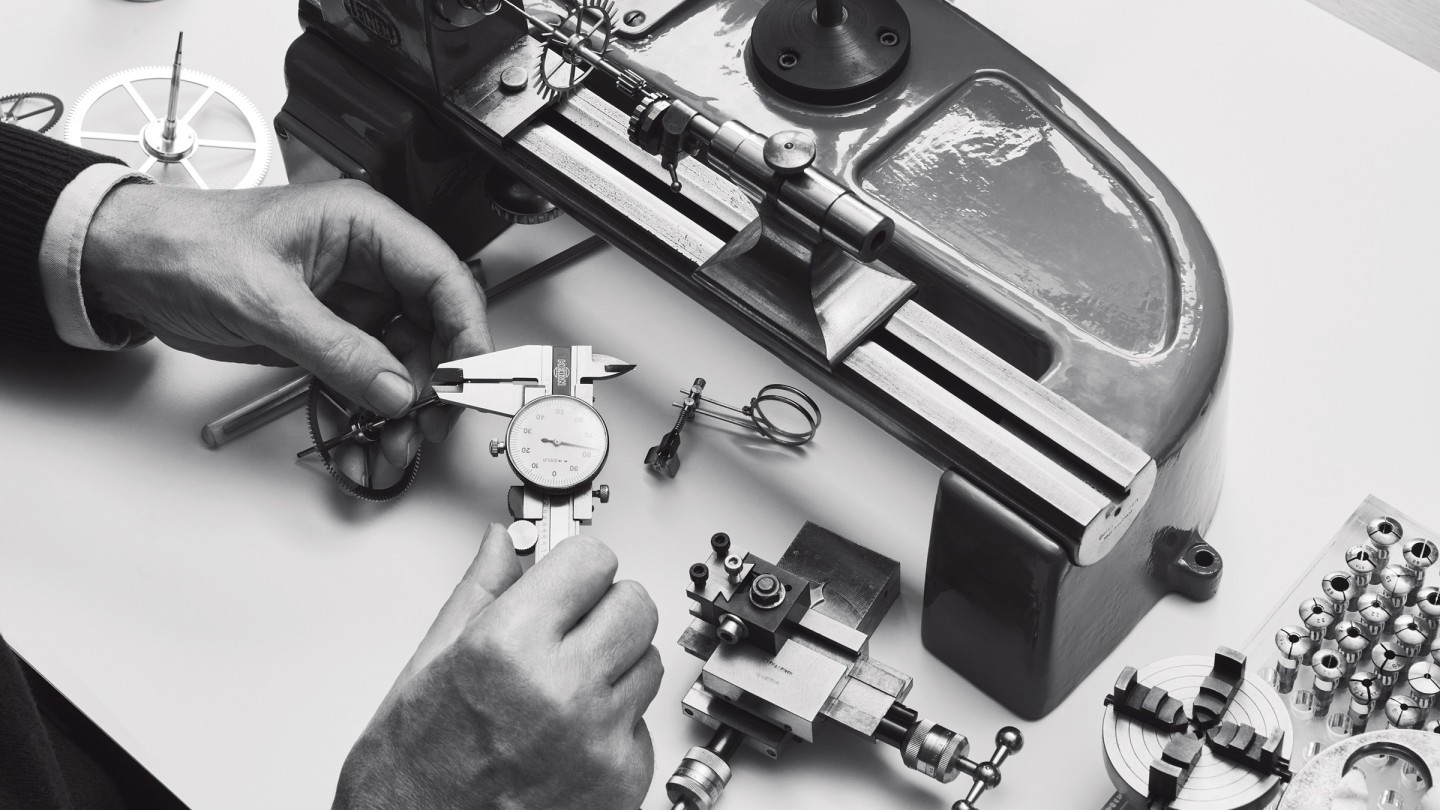

More often than not he also crafts the tools to make the parts. He speaks with a creator’s pride of a hand-built digital kiln the size of a paperback book that operates at precisely 287 degrees celsius for the bluing of screws; and a “hardness tester” for proving metal hardness with a tiny impression left by a diamond-shaped carbide point.

“I’ve been told I’m the only person in the country who’s making a clock completely,” he says. “Everybody else farms bits out – engraving, the case. Apparently I’m the only person who makes everything.” The difference is, he adds, that he regards a clock in its entirety as a work of art to be created by the hand of a single artist: “Whereas a clockmaker’s approach is quite different, he sees it as a unit to sell.”

This is not to say, of course, that his work is not for sale; a Jake Sutton clock will set you back anything from £50,000 upwards, for which you will get an object that is – give or take 10 seconds a year and the permitted imperfections of hand-engraving – the perfect marriage of high precision horological engineering and aesthetics.

View it as a work of art, a piece of kinetic sculpture, if you like. Compared to the prices of masterpieces by his college contemporaries Gilbert & George, it represents remarkable value.

Comments