Putin’s Potemkin economy

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning

Welcome back. At the start of this week, a Russian business association called for the introduction of a six-day working week to offset the impact of western sanctions. Is the country’s economy under intolerable pressure, or is it resilient enough to deliver the military victory over Ukraine that Vladimir Putin craves? I’m at tony.barber@ft.com.

First, the results of last week’s poll. Asked if Germany’s soon-to-be-published national security strategy will improve its foreign and defence policies, 57 per cent of you said yes, 23 per cent said no and 20 per cent were on the fence. Thanks for voting!

Many of you will know the name of Grigory Potemkin, the 18th-century Russian statesman and lover of empress Catherine the Great. Potemkin was instrumental in the tsarist empire’s annexation in 1783 of Crimea, the Black Sea peninsula that formed part of the Soviet Union, then independent Ukraine, until Putin reannexed it to Russia in 2014.

His name is also forever associated with the term “Potemkin village”, which means something created to make a situation look better than it really is, often to please a ruler and dupe his or her subjects. I mention this because many distinguished economists, Russian and western, think the official picture that the Kremlin paints of its wartime economy is actually one big Potemkin village.

Lies, damned lies and statistics

For instance, in this convincing article for The Insider, Vladimir Milov, an economist and former Russian government minister now living in exile in the west, refers to a set of “Potemkin indicators” that offer a masterclass in distorting the truth about Russia’s economy. These include gross domestic product, unemployment, inflation, domestic investment and the rouble’s exchange rate.

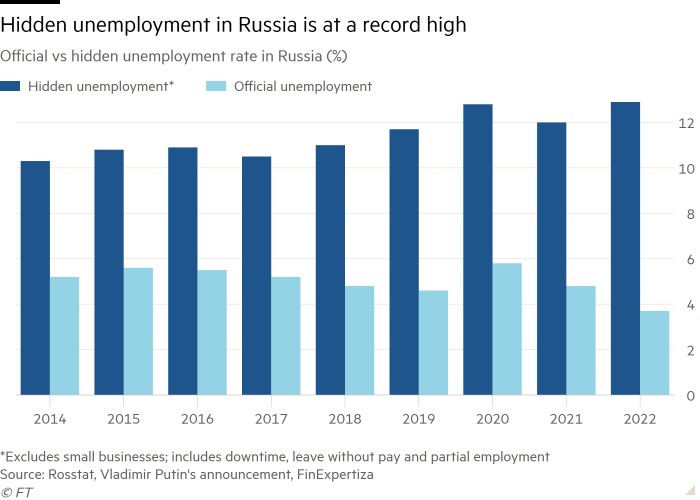

If we take just one of these indicators — unemployment — we see that Milov certainly has a point. According to the chart below, based on FT investigative reporting, Russian government data and the estimates of consulting network FinExpertiza, hidden unemployment is at a record high and way above the official jobless rate of less than 4 per cent.

So let’s agree to take official Russian statistics — that is, the ones that aren’t kept secret — with a large pinch of salt. But how misleading are they? On this there is less agreement.

At one end of the debate, Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and Steven Tian at the Yale Chief Executive Leadership Institute write:

Since the Ukrainian invasion, our data has shown that the Kremlin’s economic releases have become increasingly cherry-picked, selectively tossing out unfavourable metrics while releasing only those that are more favourable. . .

Putin is losing the military war, the diplomatic war and the economic war.

IMF forecasts

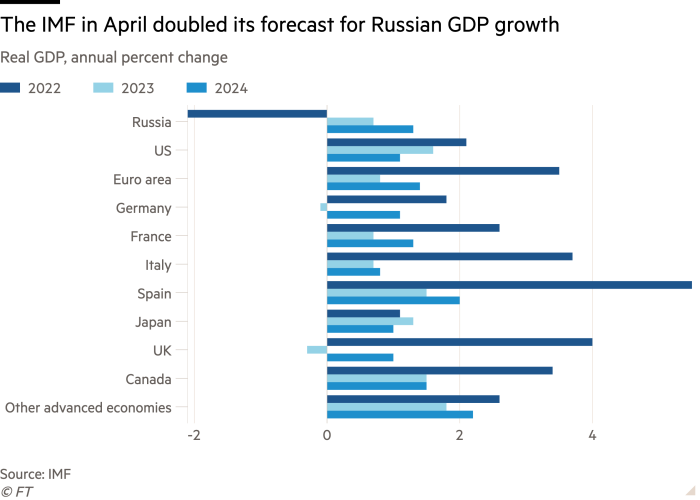

Sonnenfeld and Tian accuse the IMF of basing its relatively benign economic forecasts for Russia partly on official data that they say are sometimes “pure invention”. As we see in the chart below, the IMF predicted last month that Russia’s economy will grow by 0.7 per cent this year and 1.3 per cent in 2024 after a 2.1 per cent decline last year — nowhere near the danger levels that might cause Russia to stop the war.

Other experts, while stressing the need for extreme caution when assessing Russian data, contend that the economy continues to display a certain resilience. Lawrence Freedman, emeritus professor of war studies at King’s College London and an occasional FT contributor, writes in this Substack commentary:

The prospect is still one of short-term difficulties and long-term decline, even though the economy has not fallen off a cliff-edge and is unlikely to do so.

Another excellent review of the Russian economy’s performance under sanctions was published in March by Piotr Dzierżanowski for the Polish Institute of International Affairs. He writes:

Even weakened by the asset freeze, Russia remains one of the world’s largest economies, and the authorities retain the ability to counter sanctions by using financial reserves and administrative interventions in the economy.

This does not mean that the sanctions are ineffective — they were introduced in subsequent tranches and often provided for transitional periods, so their medium- and long-term effects are only just unrolling.

Militarisation of the economy

One Russia-born economist whose analyses are invariably worth reading is Sergei Guriev, now at Sciences Po in Paris. In this interview, he observes that one statistic the government is still publishing is that for retail sales. This indicates that, towards the end of last year, sales were almost 10 per cent lower in comparable prices than in the same period of 2021.

So the war appears to be squeezing Russian households quite a bit. This can also be deduced from data on Russian car sales, which in the first four months of this year were down almost 40 per cent from January-April 2022.

But the larger point Guriev makes is that GDP figures in wartime, even if not manipulated by pro-government statisticians, are hardly a reliable indicator of the health of an economy.

Extra spending on missiles, guns, boots and helmets — and, by the way, on the state security apparatus, police and prosecutor’s office — boosts nominal GDP growth. But it leaves less for non-military sectors such as healthcare, education, infrastructure and civilian industry, as suggested by this Reuters analysis of Russia’s 2023 budget.

Writing for the Economics Observatory, Richard Disney, research fellow at the UK’s Institute for Fiscal Studies, contends that the militarisation of Russia’s economy — combined with western sanctions — “is almost certain to induce substantial inefficiency and hence a reduction in the amount of output for a given level of input (‘productivity’)”.

Energy revenues slump

From Soviet times to the present day, GDP growth and state expenditure have always been closely associated with oil and gas exports — and here western sanctions are having some impact. Energy revenues collapsed by about 50 per cent in the first quarter of this year compared with the same period of 2022, as western price caps have caused Russian oil to trade at a discount to global benchmarks.

This leads Kirill Rogov, another respected Russian economist, to the conclusion:

As revenues decline, the economy will face the same set of problems that characterise a standard economic crisis — a chronic budget deficit, devaluation, investment hunger and demand contraction.

Long-term troubles

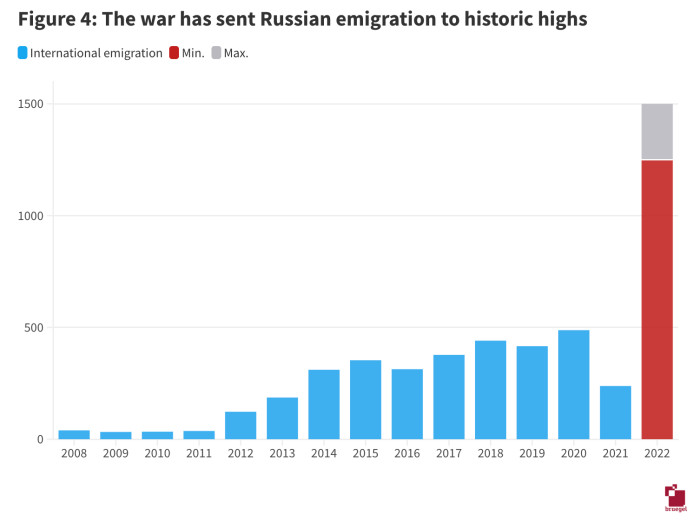

To sanctions and the distortions of a wartime economy, we can add the impact of large-scale emigration since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In the chart below, accompanying her article for the Brussels-based Bruegel think-tank, Elina Ribakova shows that emigration soared last year to record post-2008 highs — involving as many as 1.3mn people.

Many departing Russians worked in the tech sector — about 100,000, or about 10 per cent of the country’s total tech workforce, according to this first-class analysis by Masha Borak for the MIT Technology Review.

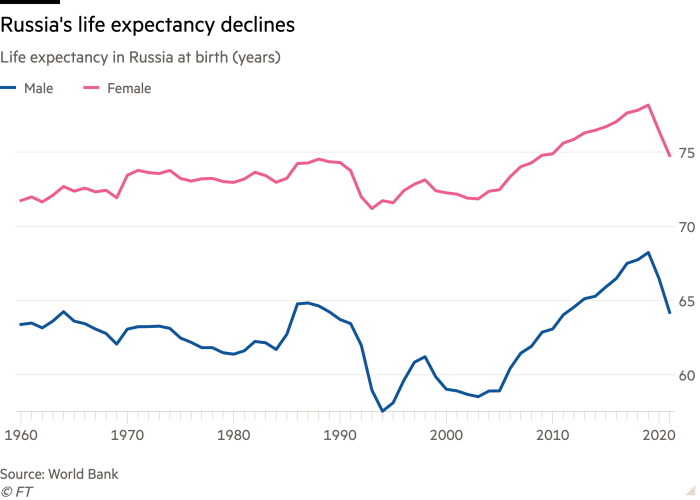

That is not only a heavy blow in itself but a reminder of Russia’s long-term demographic problems, such as relatively low life expectancy, especially among males, depicted in the World Bank chart below:

At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, Russia was recording some of the highest excess death rates in the world, according to this FT analysis in November 2021.

Does all this mean that Putin won’t be able to sustain his war effort? In the short term — by which I mean, between now and the middle of next year — I think the answer is, no. Assuming that there is no ceasefire or settlement by May 2024, I think that Russia has the capacity to fight on.

As we enter the second half of 2024, however, the big question may well be not Russia’s economic performance but the US presidential election. Any outcome that led to a scaling down of US and allied military and financial support for Ukraine would transform the nature of the war — leaving the Russian economy battered, but offering Putin the opportunity to end his neo-imperialist campaign of conquest largely on his terms.

The Russia-China relationship: the perils of a “friendship with no limits” — a commentary by Stefan Wolff, professor of international security at the University of Birmingham, for the UK in a Changing Europe research unit

Tony’s picks of the week

A new book, Die Moskau Connection (The Moscow Connection), recounts how some German political leaders were stunningly naive, before the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year, about Russian foreign policy. A review by Guy Chazan, the FT’s Berlin bureau chief

The European Political Community, which convenes for its second summit in Moldova next month, can make a useful contribution to addressing problems that the EU or Nato alone cannot solve, Sam Greene, Edward Lucas and Nicholas Tenzer write for the Center for European Policy Analysis

Recommended newsletters for you

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: europe.express@ft.com. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe

Comments