Retraining labour force for innovation is ‘challenge of our times’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When people consider lifelong learning, they think perhaps of those such as 90-year-old Joy Gibson, who has completed five degrees since retiring 30 years ago and is studying for a PhD at the University of Birmingham’s Shakespeare Institute. In the digital age, though, the acquisition of skills is not just something to enrich older people’s lives but a necessity to enable workers to survive in the labour market.

Changing technologies and ways of working, coupled with longer working lives, are intensifying demand for new skills. Online training courses provide a way for people to meet that need — if they can harness them effectively.

“Technology is racing ahead of the skills people have. This is the challenge of our times,” says Andreas Schleicher, director for education and skills at the OECD. A population with the right mix of skills can help ensure that globalisation translates into jobs and productivity gains, according to the OECD’s Skills Outlook 2017 report. However, the report also found that one adult in four has poor literacy or numeracy.

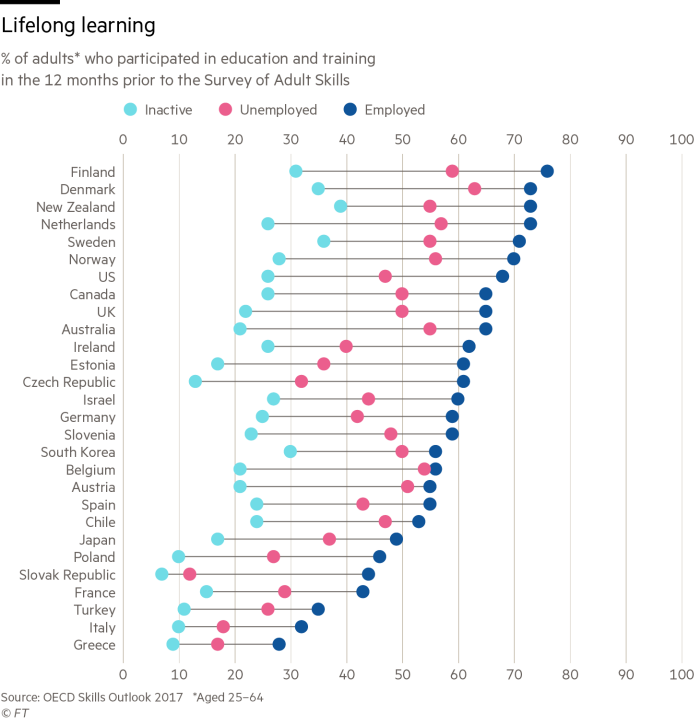

Those who are already skilled benefit most from training programmes, while the low-skilled are less likely to take part, the OECD adds.

It calls for tax incentives for learning, easier access to formal education for adults and better recognition of skills acquired after initial education.

Coding skills, for example, are sought outside the technology sector, with data analysts, designers, engineers, scientists and marketeers among those likely to need them. Softer skills such as problem-solving and communication are also valuable.

“The idea of training someone so they could do a job for 40 years has disappeared,” says Andrew Bollington, managing director of education consultancy viaEd. “Constantly refreshing our skills and learning new things is an essential part of surviving in the 21st-century world.”

Mr Bollington says schools must adapt, by not just teaching the curriculum but also equipping young people to learn for the rest of their lives. He says it comes down to “asking good questions and knowing how to apply the knowledge gained to real life”. He adds: “Some of it is about motivation as well, and how to learn without constant supervision.”

The next question is whether people ought to receive this continuous education from the state or their employer, or whether they must instead acquire it for themselves.

Most countries encourage lifelong learning, although they often allocate little money to it. According to Unesco, a UN agency, less than a quarter of countries spend 4 per cent or more of their education budgets on adult learning, while many spend less than 0.4 per cent. Singapore has learning credits that over-25s can draw on. The Nordic countries and the Netherlands and Canada have also won praise for their programmes.

The EU has a target for at least 15 per cent of 25 to 64-year-olds to participate in education or training by 2020; in 2016, that proportion was 10.8 per cent, up 1.7 points on 2011.

Employer-provided training has declined in some countries. The US Council of Economic Advisers found that the share of workers receiving either paid-for or on-the-job training had fallen steadily between 1996 and 2008. In Britain, the average amount of training received by workers fell by almost half between 1997 and 2009, to just 0.69 hours a week. Even Germany, with its admired apprenticeship system, is accused of not keeping up with the requirements of the digital age.

“It is imperative for organisations to have a lifelong learning programme in place in order to attract and retain good quality people,” says Mark Staniland, regional managing director at Hays, the recruitment company. “Millennials and Generation Z in particular are looking for lifelong learning.”

The growth of the gig economy complicates matters. “There is a growing number of non-standard forms of employment where people do not have access to any type of training,” says Olga Strietska-Ilina, senior skills specialist at the International Labour Organisation.

New ways are needed to enable individuals to learn. Among the options are massive open online courses (Moocs), which began more than a decade ago, allowing learners anywhere to sign up for courses at top universities. Today, short video clips and tests keep students engaged. Mooc providers such as Coursera and Udacity have structured courses to meet the needs of employers such as BNY Mellon, L’Oréal, Google and Facebook.

In the physical world, “boot camp” courses on coding are available from various providers.

“It’s a huge opportunity,” says Ms Strietska-Ilina, although she notes that obstacles remain, notably persuading employers and education institutions to recognise skills obtained independently. She adds: “It should become a priority for countries to work on national systems of recognition.”

Comments