How Covid-19 is escalating problem debt

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Millions of people are desperately worried about their finances during the current crisis. The sudden “income shock” that many professionals and business owners have experienced occurred without warning, and nobody can be certain how much longer it will endure.

The worst affected groups are already afraid that they will have to file for bankruptcy or another form of insolvency as their debt problems spiral.

Helplines have been inundated with queries from people wanting to know what their options are, including growing numbers of limited company directors and those who have started their own small businesses who find themselves unable to access government support schemes.

However, they fear demand will increase exponentially this summer as payment holidays and state-backed furlough schemes supporting millions of UK workers come to an end, and redundancies increase.

Half a million UK firms are at risk of collapse, according to insolvency experts Begbies Traynor. Many professionals are being asked to take pay cuts, work reduced hours or consider a sabbatical to help firms limit the numbers they will have to lay off.

At the same time, demands on the “Bank of Mum and Dad” are rising as adult children ask for help in rebuilding their finances, increasing the pressure on families who, a few months ago, would never have dreamt this could happen to them.

Here is FT Money’s survival guide for all those who are anxious about their financial situation and need to know how to find the best route through these challenging times.

Advice, please

The first thing any debt adviser will tell you is that you need to talk to someone about your financial difficulties as soon as you can. Forget any feelings of shame: most bankruptcies in the coming months will be “no fault” failures and not all are inevitable. Early intervention can help many avoid the worst.

“I’m already getting calls from people facing insolvency and many of them are directors of small limited companies who are terrified at the prospect of going under,” says Rebecca Seeley Harris, founder of Re Legal Consulting, a specialist employment consultancy.

Problems for directors are particularly acute. Most take their income via dividends, which largely rules out help from government support schemes.

“I’m absolutely staggered at the amount of people who in a very short space of time are saying ‘I am unable to cope’. The sensible ones will have retained some profits within their companies, but many won’t have that safety net,” Ms Seeley Harris adds.

Many directors of the UK’s 2m incorporated business are lobbying their MPs as they fear the cash crunch could cost them their livelihoods.

FT Money reader Julian is an osteopath operating as a limited company and paid chiefly via dividends on the advice of his accountant (“I’m a good clinician, not a tax expert,” he says).

As he operates from a service office paying an all-inclusive rent, he is not on the business rates register so is ineligible to receive a £10,000 grant — a problem affecting 10,000 small businesses.

With the prospect of no income for months, he still has to meet his business and living expenses. “I am burning through my meagre savings,” he says. Borrowing money is the only option left — but with no idea when his business can restart, he fears this could add to his problems.

PayPlan is one of the UK’s largest providers of free debt advice and has a specialist team that deals with indebted small businesses.

“You quite often get an intermingling of personal debt and business debt as people desperately try to keep things going,” says John Fairhurst, PayPlan’s executive director. “Callers are asking whether they should keep borrowing and take these government loans, as they are unsure how they can be repaid.”

However, calls are also coming in from salaried professionals on much higher incomes. A typical situation might be a couple who are working, and one loses their job. “They will be well above the benefits threshold, but their costs are way out of step with their new, reduced income,” he says.

Three-month mortgage and credit card “holidays” can provide temporary relief, but if they can’t find a new job with a similar level of pay then hard choices lie ahead, Mr Fairhurst says.

For example selling up or downsizing a home in a depressed market may have to be considered: “Something’s got to give — where do you stop digging?

“People will be reluctant to make sweeping changes to their lives, but a large disparity between income and costs means that the scale of problems quickly escalates with any delay,” he adds.

StepChange, the debt charity, says more than 350,000 people have visited its coronavirus hub page in the past month.

“People who haven’t previously experienced debt are mostly looking for forbearance,” says the charity. Once payment holidays come to an end, they will need help to unwind the additional debt accumulated.

“We are obviously seeing a lot of people who never thought they would experience debt problems experiencing them quite suddenly. The advice remains the same as ever: take advice early. By the time clients come to us they have often struggled for many months or years.”

Business debts

Business Debtline, the UK’s only free dedicated debt advice service for the self-employed and small business owners, says the challenges posed by Covid-19 are extreme.

“Nearly every call and webchat to our Business Debtline is now from someone whose business has been impacted by the outbreak,” says Jane Tully, director of external affairs at the Money Advice Trust, the charity which operates the helpline.

“In the space of just a few weeks, the incomes of millions of people across the UK have fallen significantly as a result of coronavirus, with self-employed people and small-business owners hit particularly hard.”

Although some will receive a lifeline in June when the government’s Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) starts to make payments, Ms Tully says this does not address the immediate challenge for those who have seen their incomes drop almost overnight.

The launch of 100 per cent state-backed “Bounce Back Loans” next week is designed to help small businesses that have been unable to access help from their banks. With no repayments due or interest charged for the first 12 months, applications can be made for loans of up to £50,000 or 25 per cent of annual turnover.

However, those in difficulty must decide whether taking on more debt is a feasible solution. Many small firms are braced for creditors to start threatening legal action.

Edward Judge, restructuring and insolvency partner at Irwin Mitchell, a law firm, says directors should start by listing all major creditors, tax, rates, rents, employees and suppliers.

“You need to negotiate with all those parties to reduce the amount you have to pay,” he says. “This will depend on whether you have a cash flow problem or whether it is terminal for your business.

“If it is cash flow, you will be looking to delay payment and offer to make it up in the future. But if it is terminal for your business, you need to say ‘this is what I have, and I will share it between you’ — but all of your creditors would need to agree the deal.”

In Scotland, a debt support tool for businesses allows small businesses to fulfil their obligations to creditors through a debt payment programme that allows them to continue to trade.

HM Revenue & Customs has historically been among the first creditors to start proceedings, but this is no longer the case. During the coronavirus crisis, those unable to pay mid-year tax bills can defer payment until January 2021 and VAT bills due now can be deferred until the end of June.

HMRC is also extending “time to pay” arrangements and has set up a dedicated coronavirus helpline for those affected on 0800 024 1222.

The principal advantage of a limited company structure is that directors won’t automatically lose their homes if their business becomes insolvent.

“The financial damage should be limited to the company, which means the person won’t be declared bankrupt — unless there are other issues,” Ms Seeley Harris says.

“There are also other insolvency vehicles that a limited company can access. But if you’re self-employed — trading with no limit on your liabilities whatsoever — then unfortunately, everything could go.”

What happens if I go bankrupt?

Bankruptcy is one way of dealing with debts that you cannot pay within a reasonable time — but the penalties can be severe and long term.

Any assets you have will be sold and used to pay off major immediate debts. If you own the home you live in, the official receiver or bankruptcy trustee is likely to insist you sell it. This applies whether you own it yourself or jointly with another person.

If you have family or dependants living in your home, it may be possible for a sale to be put off for a year to give you time to make other living arrangements (a charging order may be applied to the property).

If you live in your partner’s property, you may be considered to have a “beneficial interest” even if you are not named on the deeds or mortgage. Usually, it must be proved that you must have more than £1,000 invested in the property. Help with paying the mortgage may qualify, but not other bills.

To avoid putting your partner’s property at risk, you must be able to show that you will not be entitled to any of the proceeds if the house is sold.

All income, including pensions, is taken into account when deciding how much you should pay into your bankruptcy. But pensions should not usually be affected, unless it is deemed you have made excessive payments to stop creditors taking your savings.

After a year, most outstanding debts will be written off, but bankruptcy rules mean you will face drastic restrictions on your finances going forward.

Bank accounts, including joint accounts, are usually frozen when you become bankrupt, and you can only apply for a “basic” bank account after that.

StepChange says: “It’s a good idea to open a new bank account in advance of going bankrupt so your income and household bills aren’t affected.

“If you open a new basic account before you go bankrupt you can move all your income and your priority payments to the new account. The new account will still be frozen for a short time after your bankruptcy.”

Once you have become bankrupt, you will not be allowed to take any part in “promoting, forming or managing” a limited company without the court’s permission and cannot act as a director.

You will probably have to make payments from your income for three years, but you will be allowed to keep a “reasonable amount” to live on.

In England and Wales, applying for bankruptcy online at gov.uk costs £680, but there are further costs if you have assets (these are referred to as your “bankruptcy estate”). A trustee from the government’s Insolvency Service will be appointed to oversee this.

Further costs could include an administration fee of £1,990 and a general fee of £6,000. The trustee fee is usually 15 per cent of the amount they get from selling your assets, plus estate agents’ costs.

Bankruptcy remains on your credit file for at least six years, making it difficult to get any credit or a mortgage.

Debt solutions

Bankruptcy may be the best known solution, but it is usually the last resort for individuals with overwhelming debts, according to the UK’s Insolvency Service.

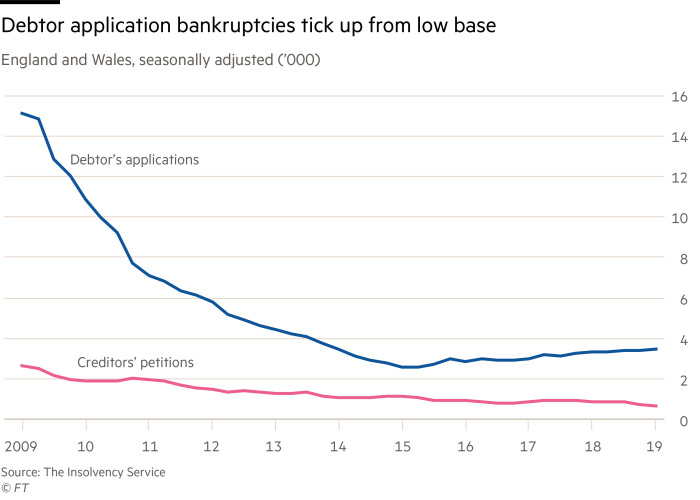

Having reached a peak of nearly 75,000 in 2009, following the financial crisis, numbers have been steadily falling — although debt advisers now expect to see a sharp increase.

“The difference with this crisis is that people are more open about their debts than they were before Covid-19 — they don’t feel the same sort of shame and secrecy about their financial problems,” says Mr Fairhurst.

Get in touch

FT Money wants to hear from readers whose finances have been affected by coronavirus. You can contact us in confidence via email money@ft.com

“One of the biggest barriers to bankruptcy is the stigma — we might start to see an attitude shift. Bankruptcy can offer a fairly quick route out of problem debt, especially if you have few assets. However, if you’ve got a decent amount of equity in your home, it’s hard to see how bankruptcy is the best option.”

If your assets are worth more than your debts, bankruptcy is unlikely to be necessary, especially if you can cover your regular payments.

“If repayment over a reasonable period is possible, this will be the approach we recommend most highly,” says StepChange, the debt charity.

“Where that isn’t the case, an insolvency-based approach may be recommended as the top option. In all cases, we will present all the suitable options that people could choose, based on their financial circumstances.”

Start by using one of the free online debt advice and budgeting tools to assess your options. Among the best are those offered by Business Debtline StepChange and Citizens Advice. This will establish your debts and potential earnings and help you to work out possible solutions.

Individual voluntary arrangements (IVAs) accounted for nearly two-thirds of all insolvencies and nearly 78,000 were entered into last year. These binding agreements allow you to repay your creditors part, or all, of what you owe and thus avoid bankruptcy — and you should be able to keep your home.

Arranged by licensed insolvency practitioners, IVAs require creditors who are owed 75 per cent of your debts to agree the terms. They then all get the same deal — usually the debtor makes monthly payments for five years, but the time period can be longer.

“The advantage is that if some creditors do not agree with the terms, they could be forced to accept the deal,” says Mr Judge. “Once 75 per cent have agreed, it becomes a contract and they have to accept it. Sometimes large creditors have a policy that they will not accept below a certain percentage voluntarily.”

However, if you are unable to keep up with repayments and an IVA terminates early, lenders can reimpose all of the frozen interest and charges.

Late payments add to woes for small businesses

Late payments were the scourge of small businesses and freelancers long before the coronavirus pandemic. In January, the Federation of Small Business predicted that 50,000 firms would go out of business this year as a result of late payments, but this threatens to become an even greater issue as clients hang on to cash.

FT Money reader Sandy runs a small joinery business, employing 14 full-time staff who have all been furloughed under the government’s Job Retention Scheme. This has saved the business, but late and unpaid invoices plus ongoing overheads mean he is looking at a £100,000 hole in the company’s cash flow — and that’s assuming things are “back to normal” by July.

Business Debtline reports that 45 per cent of callers are experiencing late payments from customers, with three-quarters saying these affected the viability of their businesses.

The charity advised Helen, whose business was owed £40,000 in invoices that had not been paid, to open new “safe” bank accounts for the business and her personal finances, so that new money received would not be immediately taken by the bank to pay debts. This also kept her business and personal spending separate.

Mr Judge said he had seen an increase in instructions to chase debts from small businesses.

“You can do this by being very persistent so that you get to the top of the list, so that a debtor will pay you to make you go away,” he says. “You can issue winding-up petitions or use a professional debt collector. You should be able to negotiate the fees now as they, too, will need the cash flow.

“Another way to increase cash flow is to give discounts to people who pay immediately. You need to get the money in. Cash is king.”

Comments