Coping with the chaos that is hybrid working

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I was promised robots. Not tedious diary co-ordination to accommodate hybrid working and a daily battle for phone chargers.

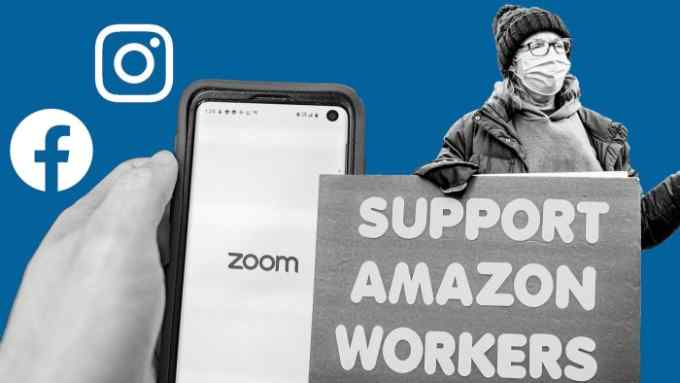

In recent years, I have witnessed the growth of what you could call ‘the Future of Work Industrial Complex’. In the pre-Covid era, on any given day you could have attended a conference, listened to a talk, or read research papers from a dizzying array of think tanks, consultancies, and influencers all speculating on the nature of upcoming jobs and work trends.

Their predicted scenarios broadly fell into two camps: the techno-dystopians who saw the widespread replacement of humans by bots and subsequent mass unemployment; or the techno-optimists who viewed machines as liberating workers from grunt work, allowing them to pursue very human jobs requiring creativity and empathy.

Well, we’re not there yet. We’ve arrived at a different future. A mid-future? It’s certainly far more prosaic than the futurists led me to believe. This one is hybrid: a mix of office and homeworking. The road ahead may be bright but it’s also bumpy. As a recent report by Microsoft put it: “Most organisations are not prepared. Hybrid work is hard.”

I am a hybrid enthusiast, though. I like a change of scene and find the company of others energising, but I also want to be able to get my head down at home and focus on projects without the background noise of conversations.

However, on returning to work after the holidays, I discovered some flaws in my new working life. First, I kept leaving my phone charger at home — asking to borrow bits of equipment might be forgivable once or twice but it soon wears pretty thin. Then I absent-mindedly scheduled meetings that meant coming into the office every day. How long before I forget my laptop?

It’s not just me. Gemma Dale, a human resources consultant and lecturer at the UK’s Liverpool John Moores University, has yet to arrive at the office with everything she needs. She points out the pandemic upturned our well-established routines, including the commute and our favourite coffee spots. Working from home meant creating a new rhythm to the day.

For many of us, going back to the office is not a return to an old schedule but “going to something different again, and no one really knows how to do it yet”. The risk of slipping back to full-time office working is a real possibility. “People are just used to doing whatever drops into the inbox or talking to whoever you happen to bump into. Hybrid requires much greater intentionality. That’s just not how we operate usually.”

For the prosaic matter of what to put in the ever-growing backpack, Dale suggests buying extra chargers and headsets. I’m not sure that I’m ready to dispense with my notebook to-do-list but I certainly have an electronic diary.

Set days vs silos

To avert timetable chaos, some organisations are setting office days for their staff. Apple wants people in on Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays. Others are less rigid and simply ask that teams come into work on the same day. This sounds great in theory, but hard to co-ordinate if you want to overlap with other departments. After all, siloed teams are said to be the death of innovation.

Casey Moore, a productivity coach, recommends grouping the items on your to-do list by location (home or office) instead of just an undifferentiated list of tasks. “It helps to move from a one-day-at-a-time mindset to a plan-a-week-ahead mindset.” She suggests taking time every Friday to plan the next week.

New FT Live event

FT’s Future of Work event series is back this October. Join Facebook, LinkedIn, AstraZeneca, Nasa, and more as they explore key themes such as omnichannel workplaces, the impact of AI on jobs, privacy and security issues in distributed workforces. To book tickets, visit here

Yet before reaching for the colour coded highlighters and immersing myself in efficiency hacks, I got in touch with Eric Abrahamson, professor at Columbia University’s business school and author of A Perfect Mess: The Hidden Benefits of Disorder. He warned me that, in difficult circumstances, people tend to “grossly over-organise — organising is not costless and the cost of organising should not exceed its benefits”.

That is not just ineffective and inefficient, it also reduces the flexibility and innovation that are essential to adapt to a rapidly changing environment, he says. “Organising reflexively, without attention to its cost and benefits, provides a temporary illusion of control and security. It makes people vulnerable to the organising industry’s panaceas — and the organising claptrap they peddle.”

I thought of this as I sat down with my partner to try to co-ordinate work, home and childcare. There are some things I can’t forget, like my son (his teacher, who called to ask if anyone was picking him up, might disagree). But for everything else, perhaps I will try organised chaos. I wouldn’t want my work to suffer after all.

Comments