Inheritance tax debate: what the wealthy need to know

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

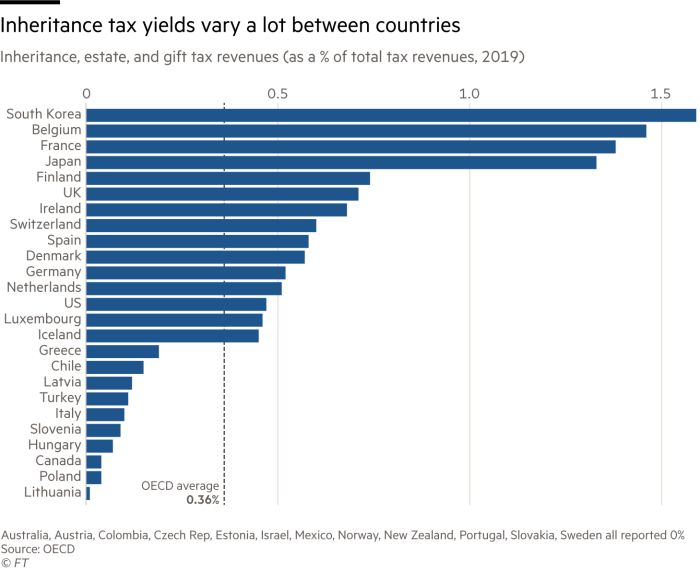

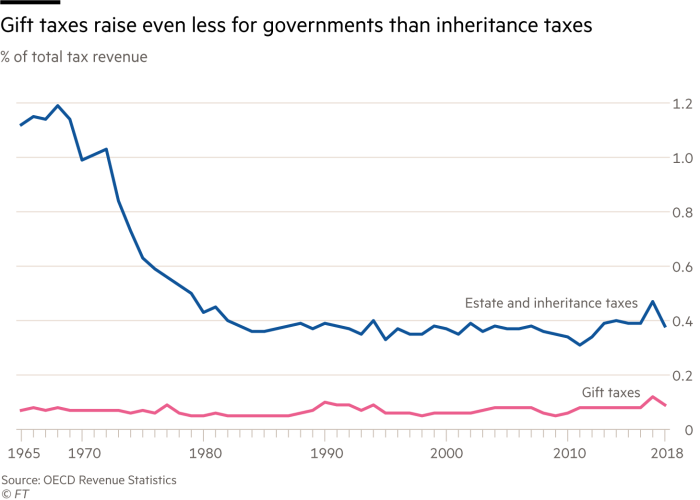

Rarely does a tax with so little financial impact generate so much argument as inheritance tax. Across the developed world, it produces only 0.5 per cent of total tax revenues in the countries where it is levied, according to an OECD report. But it produces an inordinate amount of controversy, particularly when there is any suggestion it might be increased — as is happening now as governments wonder how they are going to pay for the pandemic.

Some critics say it is fundamentally unfair to tax people twice, on the basis that IHT is charged on assets accumulated in a life of paying income tax. Others say that, far from being unfair, IHT is a key tool for making the world a better place. They argue that the emergence of a super-wealthy elite increasingly is being boosted by inherited money.

As the OECD points out, misconceptions abound. Its report cites a 2015 poll in which respondents estimated that more than half of US families paid IHT. In truth, just 0.1 per cent do. There seems to be something visceral about paying for dying — as many critics view inheritance taxes — which clouds people’s judgment.

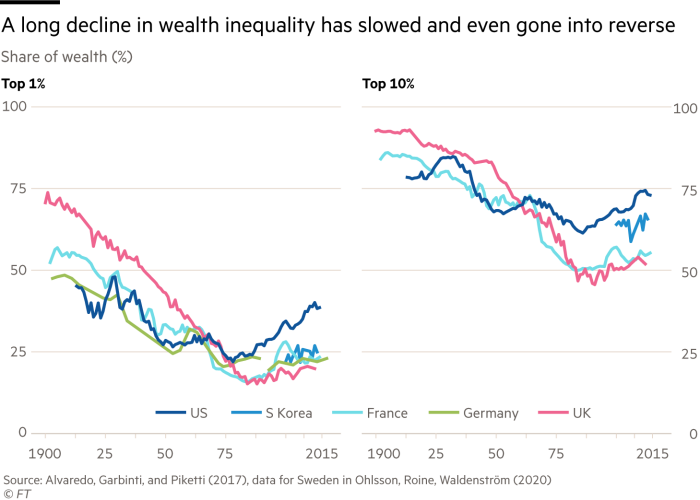

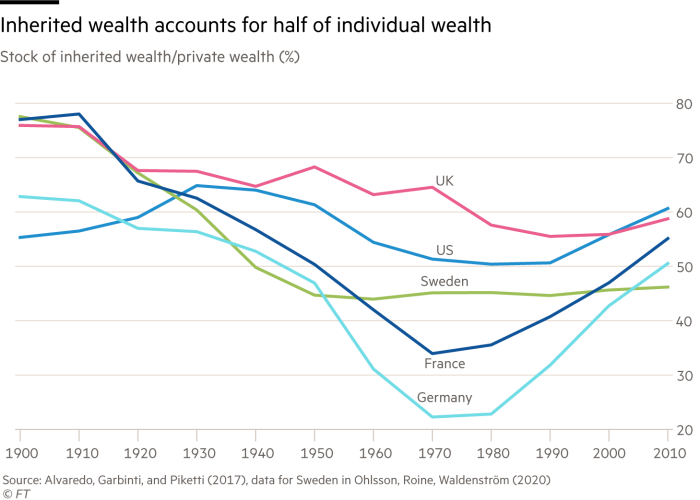

There are, however, real problems to address. The report says wealth inequality is growing in most developed countries and, often, so is the share of wealth passed down the generations. That is especially true in the US, ironically an economy built on an ideal of equality of opportunity.

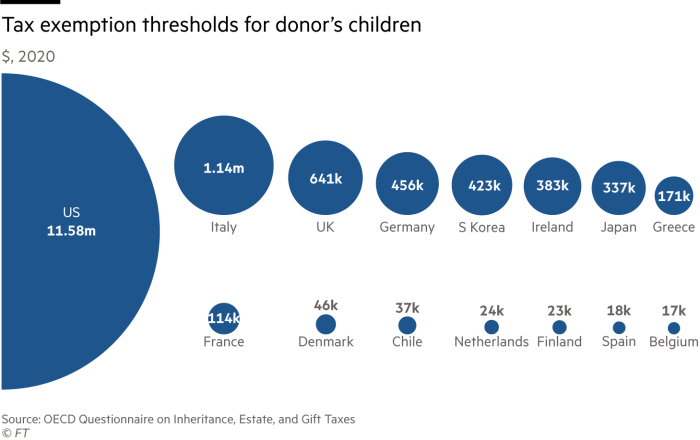

The very rich are more successful than others in reducing IHT. For a start, they are much more likely to use tax havens, where IHT can be minimised. The OECD says the richest 0.01 per cent of people own 50 per cent of tax-haven wealth. But even without resorting to subterfuge, the super-rich can shield their assets by using tax breaks that bring bigger benefits to those with tens of millions of dollars than those only with millions.

Many countries give total or partial exemptions to family business assets and quite a few do so for agricultural land, notably the UK. Some also give favourable treatment to lifetime gifts. The UK’s effective IHT rate on fortunes of £10m and more is 10 per cent, compared with 19.5 per cent on those of £8m-£9m, says the report. You don’t have to be leftwing to wonder if something strange is going on.

The OECD says inheritance taxes are well worth keeping, despite the bureaucracy, to raise revenues and enhance equality. But it calls, quite rightly, for reforms. It favours taxing recipients, as happens in some EU states, instead of the estate, as in the UK and the US. This is fairer because the tax levied would reflect the situation of the (living) recipient, rather than the (dead) donor. The OECD also suggests bringing together estate taxes and levies on lifetime gifts, thus taxing recipients on the stream of funds received over the years and not, a bit arbitrarily, only on death. As the authors concede, lifetime levies are complex to administer and tough to introduce. They may have more joy with the support they offer to cuts in IHT exemptions. They favour a broad tax system, with progressive rates and few loopholes, so the rich pay more than the rest.

The OECD acknowledges the political sensitivities. Reducing exemptions is bound to prompt criticism from those who may lose out, without necessarily being backed by those who are not affected. The answer, the report suggests, is to package reforms with other changes that promote fairness, such as cuts in labour taxes. Not to mention, cracking down (again) on evasion and unreasonable avoidance.

For the wealthy, what are the conclusions? First, have your advisers study the report, as there are deep policy differences between countries. Or, even better, read it yourself. Next, given the pandemic-driven growth in public debt and in government intervention around the globe, including the US, prepare for higher tax regimes.

Finally, for those with family businesses, do not be obsessed with passing control to the children. There may be better options for the business and the family, especially if those exemptions go.

Stefan Wagstyl is editor of FT Wealth and FT Money. Follow him on Twitter

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments