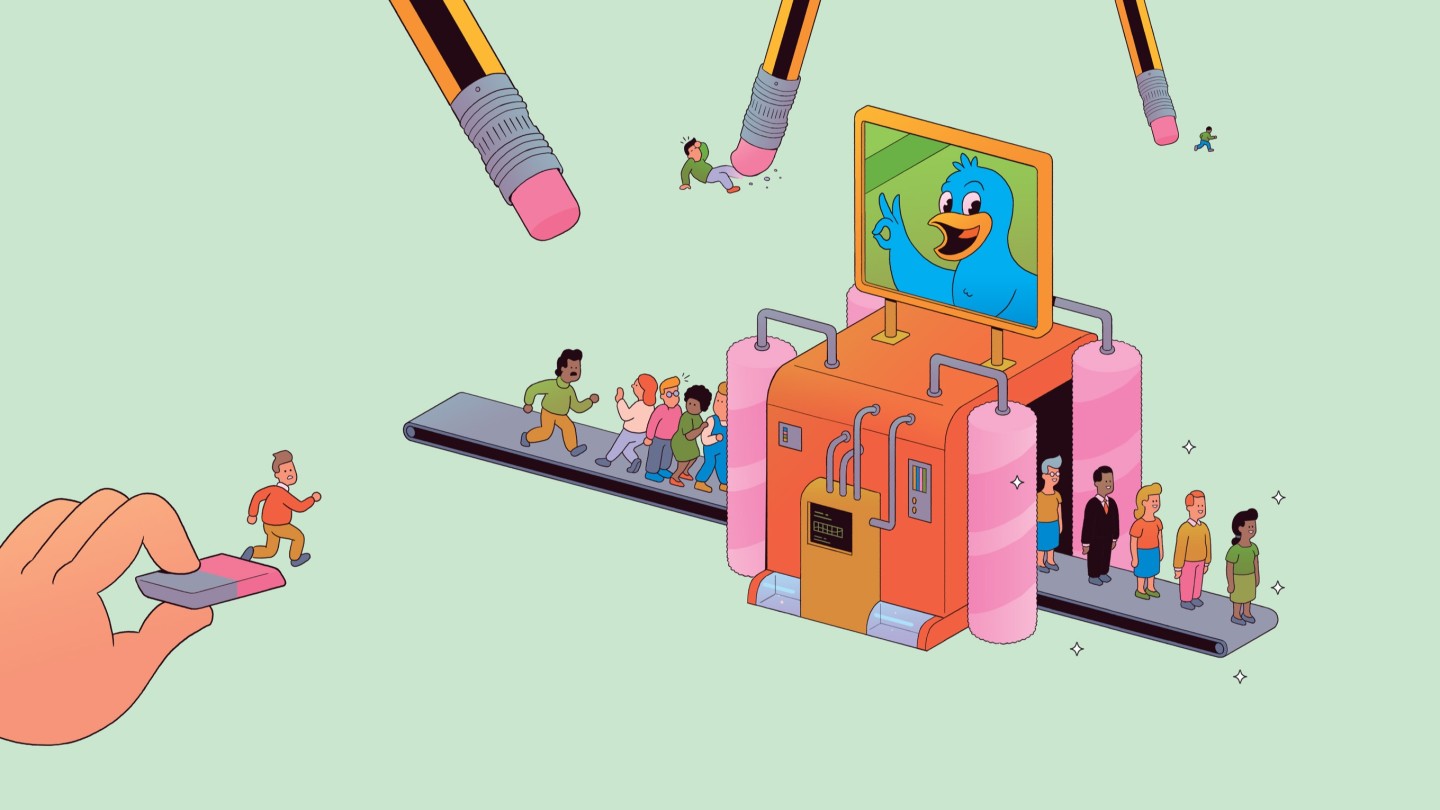

Inside the ‘digital cleanse’ companies taking on cancel culture

Gary Lineker is describing his three rules of Twitter usage. “I never tweet when I’ve had a drink. I never tweet if I’m angry… And the third one is that when I do a tweet, I read it back to myself and if I have even a one per cent doubt about it then I won’t post it. Unless I think it’s really funny and then I might.”

The former footballer, broadcaster and prolific Twitter user’s caution is symptomatic of a new digital culture in which one bad tweet can get you fired. In the febrile world of social-media activism, our professional, private and even romantic profiles are now routinely combed for crumbs of controversial content. This is a world in which everyone – from actors and television personalities to politicians, CEOs and ordinary citizens – can be “cancelled” overnight.

We live in unforgiving times. Once any kind of hastily thought-out idea, embarrassing photo or drunken attempt at humour has been committed to the internet, it becomes part of an indelible record of our lives. Recent weeks have seen a host of cancellations, or attempted ones. The longtime host of television show The Bachelorette has stepped aside after he refused to condemn the college behaviour of a contestant on sister show The Bachelor. There was an attempt to get two BBC journalists fired for their reporting on the weak evidence for puberty blockers helping children struggling with their gender identity. And last month, Condé Nast’s decision to appoint 27-year-old Alexi McCammond as the new editor-in-chief of Teen Vogue was thwarted when staffers revisited a series of anti-Asian and homophobic tweets McCammond had posted on Twitter as a 17-year-old student. In the face of fierce opposition, McCammond’s past actions were considered too great an obstacle to the transition, and the publishing house has since announced that the pair have made a joint decision “to part ways”.

Our online reputations have never been quite so important. Whether we’re considering giving someone a job, investing in their business, letting them rent out our home or even going on a date, the first thing most of us do these days is a spot of what you might call online due diligence. We Google them, we carry out an image search, we look them up on YouTube and we seek them out on social media. We want to make sure we’re not hiring a sex offender to look after our kids, investing in a serial con artist’s business or going on a date with a psychopath (or someone a lot less appealing than their curated online profile might suggest).

One of the top searches for my name is “Jemima Kelly bus”, which will tell all prospective commissioning editors, Airbnb hosts or husbands that I once – temporarily and accidentally – got a criminal record and was barred from travelling to the US because my phone ran out of battery while I was returning home on the bus. Other people must suffer the indignity of sharing their name with a criminal, a porn star or another controversial character with whom they would rather not be linked. Now, a burgeoning industry is promising to give us back control, with a host of companies specialising in online reputation management and search engine optimisation (SEO) that can help to clean up our digital footprints. Their services range from the fairly standard social-media clean-ups and online crisis management all the way to burying negative stories and setting up fake social-media accounts for those prepared to dabble in reputation management’s slightly murkier side.

The Marque, based in Mayfair, London, describes itself as an “invitation only, digital-profile management platform for leaders in their field… to ensure that you look just as smart online as you do offline”. The company insists that its ethos is not to whitewash – or perhaps “woke-wash” – a client’s digital footprint, but that everyone should be able to choose what stories they tell about themselves. Marketing itself as a kind of luxury product, The Marque describes its service as being “the new must-have”.

“Once people reach a certain level of success, they tend to drive a Range Rover, maybe they wear Savile Row suits and a Rolex,” says Andrew Wessels, The Marque’s CEO and founder, who was a professional cricket-player in his native South Africa before becoming an entrepreneur. “Now they can also have a digital twin.”

Sally Tennant, a private-banking veteran who is an investor in the company, says it is important to “look after your digital assets as you do your financial assets”. She argues that not only does The Marque “give you a hallmark of distinction that you’re a leader in your field – a stamp of credibility”, but also, and especially during lockdown, when we’ve been forced to get to know people digitally, the service offers “a much more rounded view than on LinkedIn”.

For around £3,000, the cost of its basic profile service, The Marque assigns clients a dedicated “profile manager” to build a digital profile that includes an up-to-date biography, as well as embedded links to social media, videos, articles and anything else the client wants to include. The company’s SEO team, meanwhile, tries to ensure that The Marque’s profile comes high up on the first page of results on a Google search, and the company also provides “performance reviews” on a regular basis so that clients know how much their profile is being looked at and from what location. Furthermore, it will soon launch a “digital briefcase” service, with prices starting at £13,000 per annum, which will also provide an annual “digital audit” that will highlight any reputational, security or privacy risks it encounters and make recommendations to help with those. As part of this new offering, The Marque will also offer “24/7 listening”, a service that will monitor both traditional and social media for any mentions of the client, marking any “red flag” moments and sending immediate alerts.

Former Sainsbury’s boss Justin King, one of The Marque’s clients, tells me that part of the appeal of having an SEO-optimised profile was that he was sick of people looking him up on Wikipedia and emailing him to ask if he was the guy who took away the Christmas bonus. “Forever, my Wikipedia profile will tell you that I’m Scrooge,” he says. “The idea that you could keep a single source of truth in one place – my truth about me and what I do – was very appealing.” For Gary Lineker, another client, having a profile on The Marque was less about offsetting bad press and more about having all his information in one place and up to date – particularly useful for someone like him, who has no assistants and runs his own diary. “It’s like a website, but I don’t have either the time or the motivation to make my own website,” he says.

While he’s learnt to police his own social-media platforms, Lineker, 60, is sympathetic to those footballers now entering the profession who do not have the luxury he did of being allowed to make mistakes off the pitch because of the permanency of the internet. “I’ve seen things with footballers where they’ve tweeted stuff aged 15, 16, 17, and you’re obviously not mature enough to know what you really think then – we all change in time,” he says of “cancel culture”. “Would any of us really want to be judged on what we thought and said at 17? Probably not. I’ve definitely changed as a human being as I’ve got older.”

BrandYourself, a New-York based firm that does pretty much what it says on the tin, caters to what Patrick Ambron, the company’s CEO and co-founder, calls the “full gamut” of clients, ranging from teenagers hoping to boost their prospects of getting into university to high-profile public figures who need a more comprehensive approach. One of the company’s most popular products is its “social-media clean-up”, which constitutes a thorough check of everything that someone has ever done, said and even “liked” across their social-media platforms, and then flags up potential issues that might surface in the years ahead. “For better or worse, there’s definitely more scrutiny of how people present themselves online now, especially if you’re high profile,” says Ambron. “If you look at college athletes, for example – all of a sudden they get thrust into the spotlight and people start reading years’ worth of tweets and posts. We’ll show you things that could get flagged as negative… Our stance is that, for all its good intentions, online screening is an invasion of privacy and it doesn’t always get it right.”

Dave King, who runs the London-based Digitalis, which looks after the online reputations of ultra-high-net‑worth individuals as well as businesses, says that over the past few years there has been a move away from trying to remain anonymous online – an undertaking that is becoming almost impossible – and towards taking control of your digital footprint instead. “Ten years ago, ‘What do I look like on Google?’ was a secondary question in media relations,” he says. “Today, it’s often the first.” He adds that online-reputation-management companies are more important today than traditional PR firms, many of which offer their own services in this field, but most of whom don’t have the same level of technology or expertise they do.

Terakeet is the New York-based firm that led the SEO strategy for Barack Obama’s presidential campaigns in both 2008 and 2012. Today, its key focus is on the corporate world where clients – mainly Fortune 1000 firms, but also ultra-wealthy individuals – pay on average $150,000 a month to have their online reputations taken care of, with some paying more than $2m a month. “Most companies call us when the building is on fire,” says the company’s CEO and co-founder MacLaren Cummings. “But the best time to do this is actually not when there’s a lot of heat on a company or CEO, it’s when it’s relatively quiet and the company is enjoying a period of great reputation.” He also argues that there is still too much focus on paid search results – those that come up with a “promoted” tag – and not enough on organic ones. “Most companies spend a disproportionate amount of their money on paid search, even when a company is in crisis,” he says. “It’s almost hilarious to me. Like when BP had the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, I Google BP and… the first thing I see is an ad that says ‘BP cares’. Everybody knows they bought that ad!”

At the other end of the spectrum, companies such as the London-based Pure Reputation offer a more temporary service, with starting prices of around £1,500 a month to deal with issues that the ordinary person might encounter. Such as the client who got turned down for a job because his prospective employers had searched him online and found some sexually explicit pictures. Even though the images were nothing to do with him, the fact that the company’s clients might look him up and find them was considered sufficient risk that they decided not to offer him the role. “Even if it’s not him, if they hired him to be in a client-facing role, and then a client Googles his name, it’s still going to embarrass the company,” explains Simon Leigh, Pure Reputation’s managing director. The man has now removed his first name from his LinkedIn profile as a first step, but is using Pure Reputation to try to prevent the problem from happening again.

Pure Reputation takes a mixture of simultaneous approaches to help improve its clients’ online reputations. It might go directly to Google and ask them to remove material on the grounds of defamation or the right to be forgotten. It also pays people small amounts of money to visit and engage with other sites that come up when you Google someone so that those results appear at the top and the more embarrassing ones move further down.

The risk, surely, in using all these services is that we will create an online presence that is so flawless, we cannot help but be a crushing disappointment when anyone meets us IRL. It would be dishonest for us to claim that we don’t look people up online and make assessments before we’ve met them. But much as we might wish that our online reputations didn’t matter, it seems increasingly difficult to argue that they don’t.

However, before we all rush out to create a “cancel-proof” digital presence, maybe we should also consider becoming a less censorious society that allows for people making mistakes. If we don’t, we might end up with a world in which only the most compliant and banal people – those who have never dared to deviate from the consensus – or those who have been wealthy enough to afford the most deep-dive online-cleansing services, are vaulted into positions of real power.

Comments