A more sober outlook weighs on investors

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Autumn has set in and investors are looking back at a period of summer exuberance in markets through a notably more sober lens.

The focus is the curious moment in July when some fund managers abruptly convinced themselves, after a dreadful start to the year, that the US Federal Reserve would decide to be merciful. Stocks shot higher over hopes it might hold fire on some of the more aggressive options for taming inflation.

It was no fleeting fad. At the extreme, from mid-July to mid-August, the S&P 500 benchmark index of US-listed stocks gained about 16 per cent. The MSCI World index jumped by a similar degree. But anyone who timed this summer respite perfectly is in a minority. Now, investors are hunkering down for a grim winter after the Fed made it very clear it did not intend to budge.

“The narrative of the summer rally in financial markets that central banks might slow or even reverse rate hikes soon is now clearly out of the window,” said Michael Strobaek, chief investment officer at Credit Suisse. “Markets had factored in too much hope and not enough economic realities.”

To some, the summer rally was a grim omen. GMO’s Jeremy Grantham told readers that fleeting periods of optimism were “perfectly” in keeping with a “superbubble” on the brink of popping. “Prepare for an epic finale,” he warned.

True to form, the cheery vibes have fizzled out — that rally has almost entirely evaporated. Now the rest of the year will be about the earnings that underpin valuations, and managing expectations.

“I don’t think we should say to clients that we think [markets] will rip back up,” says Nick Thomas, a partner at Baillie Gifford, one of the UK’s most high-profile investors in high-growth stocks. He acknowledges that market conditions are “painful”, in sharp contrast to the runaway rallies that fired up Baillie Gifford’s portfolios last year.

The real clash of views now is whether fund managers can avoid stepping on any more rakes. Michael Wilson, an equity strategist at Morgan Stanley in New York, suspects not. So far, he writes, interest rate expectations and bond market ructions have inflicted the real damage on investors in 2022. In other words, if you like, you can blame the Fed for the poor performance of your investments in the first half of this year.

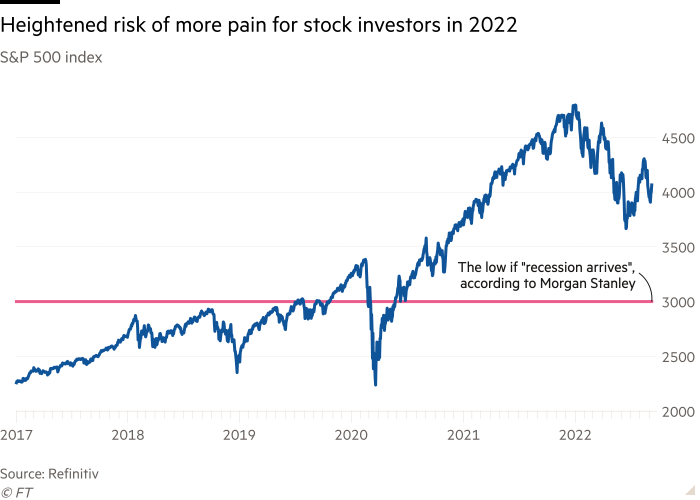

Now, though, that excuse is wearing a little thin. Instead, what Wilson calls the “fire” of adjusting to a new monetary environment is giving way to the “ice” of economic stress weighing on company earnings. He thinks the S&P 500, now hovering at around 4,000, is still in for a shock.

“While acknowledging the poor performance in equities [so far this year], we do not think the bear market is over if our earnings forecasts are correct. We think the lows for this bear market will probably arrive in the fourth quarter, with 3,400 the minimum downside and 3,000 the low if a recession arrives,” he says. Just the fact that stocks have already fallen hard, and that few have been spared the suffering, is “not a sufficient reason to be bullish”, he says.

But this key point, on earnings and the damage they could inflict, is where the arguments set in. “Everybody already knows all the bad news. Sentiment is already at rock bottom,” says Thomas at Baillie Gifford. “The fact that earnings are going to fall is not a surprise to anybody.” He is quietly confident that stocks will wrap up the year in relatively serene style.

If he’s wrong, one source of succour may be the very same bond market that led the stocks rout in the first place. Of those two major asset classes, it has had an even more horrible run.

“Global bonds have entered the first bear market in a generation,” UBS Wealth Management’s Mark Haefele noted, after government and high-quality corporate bonds dropped more than 20 per cent from their 2021 peak, according to the snappily named Bloomberg Global Aggregate Total Return index.

Yes, 20 per cent is an arbitrary number. Nonetheless, this is the worst period in this market, the bedrock of global asset prices, since at least 1990. UBS also points out that August was the worst month for European government bonds ever, while the US market has dropped 12.5 per cent from its highs — more than double the scale of any peak-to-trough pullback since the 1970s.

That means anyone hoping bonds would fulfil their usual function and provide a counterbalance to crumbling stock prices has been having a dreadful year. The good news is that such periods of simultaneous pullbacks in bonds and equities are rare and, since 1930, they had given way to bond rallies “100 per cent of the time”, UBS said. Barring a break with precedent, that means the safety net is back.

Stocks are down but not out. A jump earlier this week suggests the “epic finale” hypothesis is still in the minority. But stress and volatility in every major asset class are here to stay. Forget the chance of a proper recovery. Anything better than a further 5 per cent drop by the end of the year would probably count as a win.

Comments