Adam Curtis: my hope manifesto

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

What comes to mind when you think about hope? My immediate reaction is how the whole idea of hope has become diminished over the past 20 or so years. The moment that seemed to express early on what was happening was in a speech made by President Bush immediately after the attacks of September 2001. He urged the American people to fight back against terrorists by going shopping. It was an act of defiance that was widely mocked at the time – and it is cheap to take it out of context of the rest of what he said. But it did bring into focus the shift that had happened in the US since the mid-1980s – and what hope for the future had become. So many factories had closed, and millions of jobs had been exported overseas. Wages had stagnated or fallen – and millions of people borrowed money to go shopping. In the face of terror, hope was now focused on keeping that system of debt going. People spent their weekdays doing what became known as “bullshit jobs”. Their real job was in the evenings and at the weekends – to go shopping.

Is hope passive or active? The neoconservatives had hope. They had an extraordinary vision of using the shock caused by 11 September to launch an invasion of Iraq. But for them that was just the start. They believed it would be the spark of a revolution that would roll across the countries of the Middle East – and lead to the rising up of democracy, everywhere. That kind of hope was rooted in their own past – because the early neoconservatives had emerged from the fracturing of the American revolutionary left in the 1950s. But they also had a dark and pessimistic vision because they didn’t trust the people with that hope. Instead, they used fear to persuade the American people to back the invasion. They created a massively exaggerated fear of al-Qaeda as a hidden “global network” that was planning to destroy “western civilisation”, and a fear of weapons of mass destruction hidden in the desert. I do think that the decision to use fear and deception to justify the Iraq invasion was one of the major factors that destroyed the trust of millions of people in the hopeful idea that politicians, and journalists, could be believed – and trusted to change the world for the better. A disillusion that we live with today.

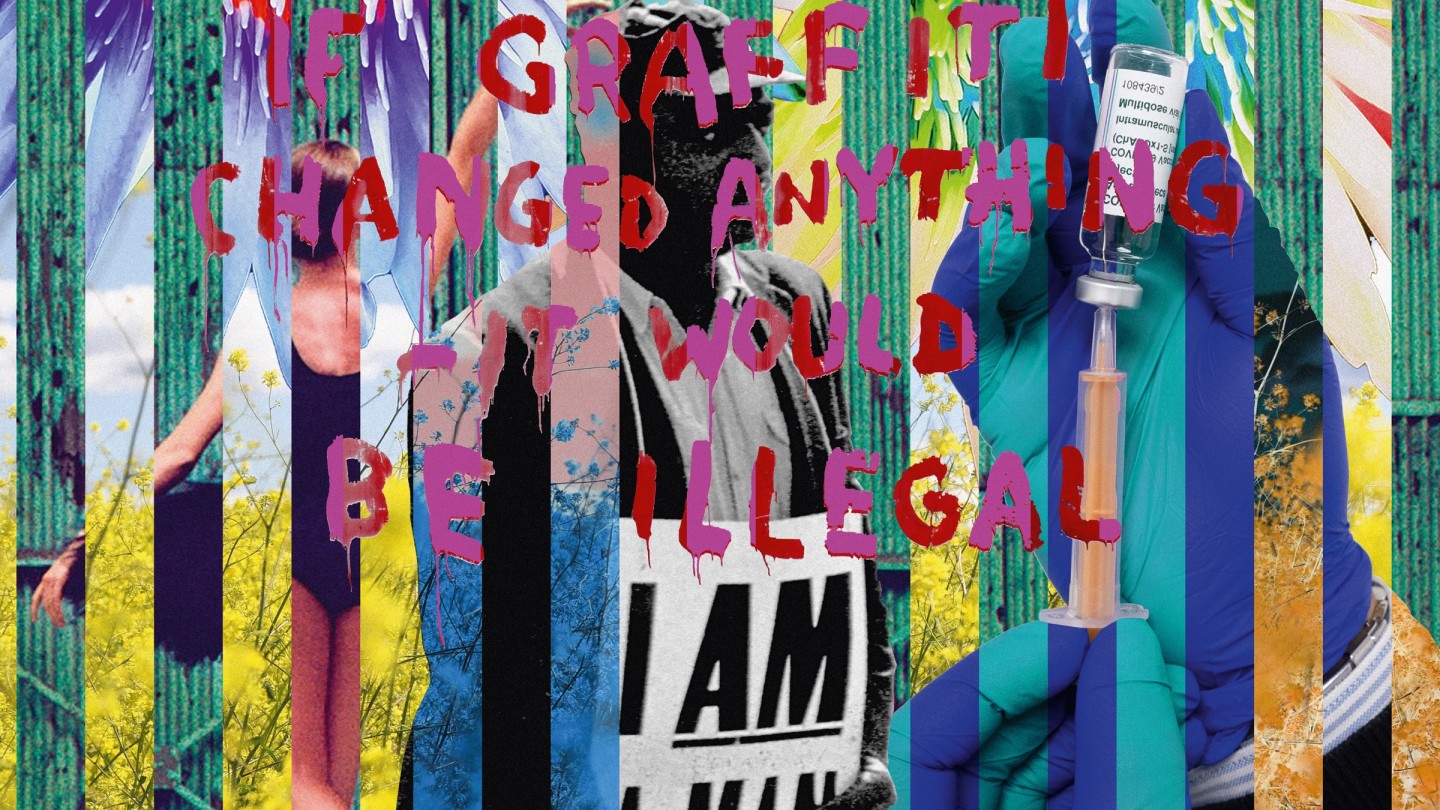

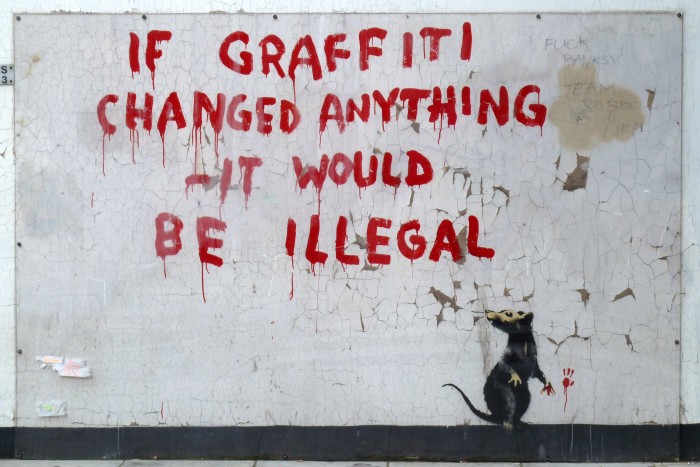

What single image encapsulates hope? The one image that I think encapsulated what had happened to the idea of hope by the end of the first decade of the new century was a piece of graffiti created by Banksy in 2011 in central London, which reads “If graffiti changed anything – it would be illegal”. It summed up how by then the idea of radical change had been sealed off in the zone of culture – where self-expressive individuals could act out revolution in a safe space. While outside nothing changed. Good Banksy – he spotted what was happening.

What films and books inspire hope in you? I’ve always loved films and books that pull back and give you a sense of seeing the world in a different way, that the reality field around us might not be everything – or last forever. That’s why I love Stalker – despite it being nearly three hours long with no jokes. It’s why I also love Anchorman, because it makes you realise how strange and silly – and fundamentally unreal – modern TV news is. Plus it has jokes. And the most inspiring book is Jerusalem by Alan Moore. It makes you imagine how there might be completely different ways of seeing that very same reality that we experience every day. Set in half a square mile of Northampton. It’s wonderful.

Is there such a thing as a hopeful smell? Well, there was “Eau de Subprime”. Then there was “Parfum d’Austérité” and “Essence de Libor”. And then there was “Hope by Barack Obama”. And I know which ones did best.

Which works of art transport you? “Come Down To Us” by Burial. One of the most powerful and beautiful pieces of music in the past few years. More than that, it captures the complex feelings that underlie our anxious and uncertain time. In its 13 minutes, it expresses the mix of fear and solitude that has risen up in the age of individualism, combined with a powerful romantic yearning. A feeling of certainty that there is something more than just this to be found. And that together we will find the way to get there, and the power to achieve something different and better. It ends with a very moving speech by film director Lana Wachowski.

What passages or reading material do you turn to for reassurance, or optimism? The activist David Graeber, who sadly died last year. He invented the idea of “bullshit jobs”. But he also wrote: “The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.” I also like Malcolm X’s observation: “A man who stands for nothing will fall for anything.”

The word “hope” gained political currency in the run-up to the Obama administration. Does it still have the same relevance? During the time of the Obama administration, there was a wave of uprisings driven by the hope of confronting corrupt rulers or systems of power. First there was Occupy – with a really good slogan, “We are the 99%” – which captured people’s imaginations. Then came the uprisings across the Arab world – when it seemed as if democracy might rise up and get rid of the dictators. Then there was Donald Trump who, remember, promised a radical transformation. He would end corruption in Washington, bring the factories back from China and rebuild industry, repair the infrastructure – and end foreign wars. He failed in everything. But so did the other revolutions.

I think the question of our time is why did all these attempts to change the world fail? Why was hope not enough – whether you agree with it or not. Because I think the answer highlights the problem at the heart of western societies. That something much bigger is going on – and all three failures are symptoms of a system of power that works today in a much subtler way than power worked in the past.

It has managed to seal much of the radicalism off from the other areas of society. Not just – as Banksy pointed out – by isolating it in the world of radical art, but also by containing it in the world of social media. In the four years of the Trump administration, Trump and his liberal opponents became locked together in a feedback loop of mutual hatred and outrage that effectively sealed them off from the real world of power, outside of their co‑dependent pantomime.

Trump’s real role was as the distraction. And the others – Occupy and much of the Arab Spring – also got locked into the idea that somehow the new networked systems underlying social media were more than just a way of bringing revolutionaries together. They believed that they could also be the model for the new, alternative society that they so much wanted to create. But again, they became increasingly detached from the complexity of the real world outside – and the struggles of power-changing it would involve.

I think that isolation then led to a diminished idea of how much change is really possible – and how difficult and brutal it might be. That even when we are opposing the powers that be today, we are not really expecting dramatic structural change – change that would be frightening as well as thrilling.

You have to rise above the world as it is and see in a completely different way. Only then will you be able to imagine something genuinely new. I think it is what is called a paradigm shift.

What makes you feel most hopeful? The knowledge that history is always dynamic. Which means that the present managerial ideology that has taken over politics will not last. I have always liked the character in Tolstoy’s War and Peace – Marshal Kutuzov. He is the very opposite of Napoleon. Napoleon believes that you can control the great forces of history and bend them to your will. Kutuzov sees reality instead as complex and chaotic – but he knows that there are moments when that reality comes together in a way that means you can use its power to get what you want, to push reality towards something new. Kutuzov lets Napoleon come to the gates of Moscow and beyond. And then at a key moment he acts – and the world changes.

What moments in history give you hope for the future?

The American Revolution.

The rise of mass democracy in the late 19th century through to today.

The rise of popular journalism and a muckraking press whose aim was to challenge unelected power on behalf of the people.

The invention of the washing machine.

The creation of the Welfare State and the National Health Service in Britain.

The civil rights movement in America and the Black Lives Matter movement now.

The rise of modern science and its extraordinary record of transforming and saving people’s lives – including the creation of the vaccines in record time last year.

The internet before it was taken over by venture capital in advance of the dotcom crash in 2000.

The end of the European empires.

South Park.

What causes should we give ourselves up to? Causes that want to change the world for the better. I don’t buy into the contemporary pessimism that says reality is too complicated for human beings to change in the way they dream of. For evidence, see the previous answer [“What moments in history...?”]. We made this world – both the good parts and the bad parts – which means that we can make it different. But perhaps we shouldn’t write columns about it. Or post photos online about it. We should just do it. Just as black and white activists did in the civil rights movement; they gave themselves up to something they knew was greater than themselves as isolated individuals. And they did something extraordinary that lives on beyond them.

What is your favourite view? It changes, but at the moment it’s the shot from the Perseverance rover as it descended to its landing point on Mars, and the vision of the horizon beyond. The landing point is named by Nasa after the American science fiction writer Octavia E Butler.

Does hope have a sense of humour? Yes. Lex Greensill and the dramatic collapse of his finance company. Like Melmotte – the financier in Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now – Greensill had used the promise of money to work his way into the heart of the establishment, was given a CBE by Prince Charles and then employed David Cameron. But not just on a retainer; Greensill promised Cameron a windfall of millions of pounds on stock options.

And then it all collapsed. One of Cameron’s former colleagues was reported to have said: “It seems that everything he touches turns to dust.” It’s like a comic-book illustration of the emptiness and the cronyism of our time. And in its comic exaggeration may do more to change things than earnest politics tracts.

But the comedy is not just on the right. I loved the waves of outrage that were unleashed by Maggi Hambling’s statue of Mary Wollstonecraft. It’s hopeful because it shows the energy waiting there to be unleashed, but again it is still locked up within the walls of culture. And trapped in the self-expressive radicalism that found its slogan in the march against the Iraq war in 2003 – “Not In My Name”. A slogan that cleanses the soul, but does little to change society or challenge power.

Does hope have a soundtrack?

“Push The Button” – Sugababes

“Bounce It” – Juicy J

“1979”– The Smashing Pumpkins

“Anywhere”– Rita Ora

“Eternal Spring” – Grazhdanskaya Oborona

“Your Loving Arms” – Billie Ray Martin

“Les and Ray” – Le Tigre

“Poison Dart” – The Bug (featuring Warrior Queen)

“Six Sixth Street” – Louisa Mark

“Opening Night” – Natalie Beridze

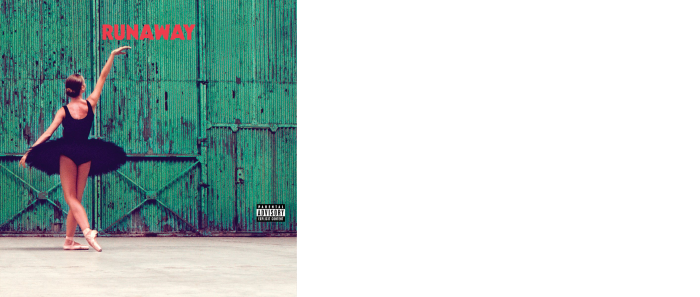

“Runaway” – Kanye West

What do you feel hopeful about in 2021? That the idea the internet is somehow a magical force will fade away. The internet will still be there – but the notion that big data and AI can see a hidden reality will go. People will come to realise that those magical claims that Google started to make 21 years ago – that through the data they could predict what individuals wanted, and how they were feeling, and how they would behave – was actually a big con. That really they know very little. No more than the old advertising they replaced. But we believed them because we were anxious and frightened of the catastrophes that kept hitting us. And we gave up hope and settled for so little.

Adam Curtis’s six-part documentary, Can’t Get You Out of My Head, is on the UK’s BBC iPlayer

Comments