BP: rebuilding trust after a disaster

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Carl-Henric Svanberg’s long-term prospects as BP chairman did not look promising in June 2010, when he emerged from an emergency meeting at the White House about the unfolding Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Mobbed by a scrum of reporters outside the West Wing, the Swede tried to express empathy with shrimpers and fishermen facing ruin from the black tide washing ashore from Florida to Texas. Instead, an unintentionally condescending declaration that BP cared “about the small people” only deepened perceptions of an out-of-touch British company struggling to cope with the worst oil disaster in history.

“I was supposed to take a couple of questions but ended up taking six and it was the last one which got me,” Mr Svanberg, 65, recalls, still bristling eight years later about the perils of going off-script in a second language.

BP’s initial handling of Deepwater Horizon was a case study in how not to manage a corporate crisis. As Mr Svanberg prepares to step down as chairman later this year — he will be replaced by Helge Lund, a fellow Scandinavian — Mr Svanberg’s survival, and the company’s recovery, have become a source of lessons on resilience and redemption in business life.

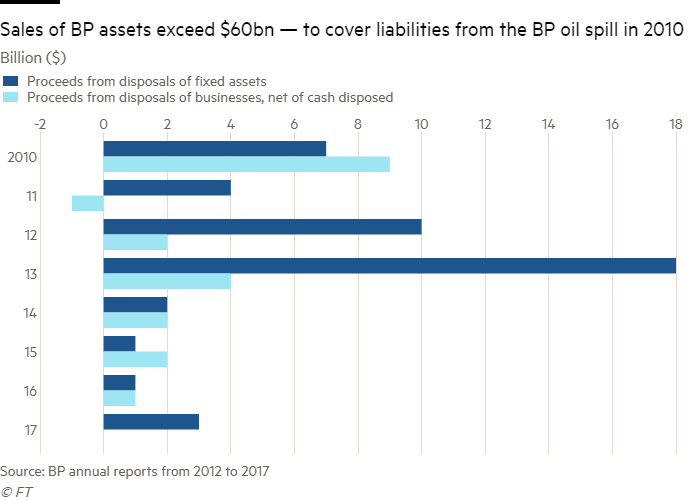

“We have been able to bring back BP to the size and strength it was before the accident,” he says. It has been a tumultuous process that involved the sale of more than $60bn of assets to cover disaster liabilities, followed by a rebuilding process that has only recently begun to restore a sense of normality to the company.

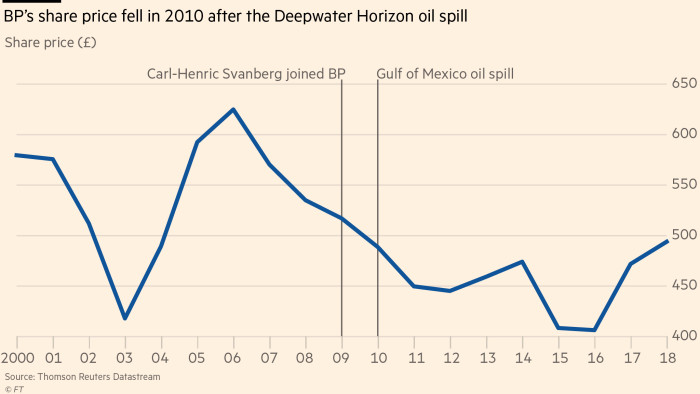

Back in June 2010, it was far from clear that BP, let alone Mr Svanberg, would still be here in 2018. Its share price and credit rating plunged. Despite the “small people” headlines, Mr Svanberg’s meeting with Barack Obama was a turning point. “We sat in the Oval Office and I said to him: ‘Our boat is keeling over right now. We’re not taking on water but we’re not far away. If you and the administration can be supportive going forward, that would help us do the right thing.’”

Mr Obama, who had until then used BP as a political punchbag, responded with a statement that it was in America’s interest for the company to remain “strong and viable” so it could complete the clean-up and pay compensation. Investors and creditors took this as a sign of the president calling off the dogs.

But Mr Obama’s message did little to restrain lawyers, who converged on the Gulf coast to help tens of thousands of local businesses to file claims for lost profits. BP’s bill for compensation, penalties and clean-up has topped $65bn and is still rising as the last civil claims go through the system. “Would the Americans [ExxonMobil or Chevron] have got off cheaper? Probably,” says Mr Svanberg, speaking in BP’s headquarters overlooking St James’s Square in London. “Were there things that, knowing what we know now, we could have done differently? Probably. But you do the best you can at the time.”

Battling with US lawyers and politicians was not the job Mr Svanberg imagined when he joined BP in 2009 from Ericsson, the Swedish telecom equipment manufacturer. His main attribute appeared to be experience in India and China, from where the strongest growth in energy demand was coming. His Scandinavian roots were another attraction when the Nordic model of responsible capitalism was the height of fashion after the global financial crisis.

Three questions to Carl-Henric Svanberg

Who is your leadership hero?

Nelson Mandela. His moral leadership brought apartheid down and afterwards he forgave his enemies.

If you were not a business leader, what would you be?

My parents urged me to pursue a secure government job. After high school, I started training to become a teacher of maths and science but, even with top scores, you had to enter a lottery to get a job — so I decided to switch to a degree in applied science.

What was the first leadership lesson you learnt?

During national service, I led my platoon crawling up a hill during a live fire exercise. I got to the top 20m ahead of my comrades [who were] waving their loaded guns at my backside. That taught me the importance of bringing everyone along on the journey.

Yet Mr Svanberg’s brand of leadership was hardly soft. He made his name as chief executive of Assa Abloy by buying and integrating dozens of small family lockmakers, many of them badly run, into the world’s largest lock manufacturer. That earned him the top job at Ericsson, where he led a successful turnround after the dotcom bubble burst, but only by shedding tens of thousands of jobs. How was such a brutal restructuring possible in a country with a strong consensus culture and labour representation on company boards? He says it is easier to enlist unions’ support for tough measures when they are part of the decision-making process rather than outsiders engaged in adversarial negotiations.

Mr Svanberg, who also chairs Volvo Group, the Swedish truckmaker, was born in Porjus, a village in the Arctic Circle. He moved house 10 times before he was 15 as his accountant father was transferred between hydroelectric projects by the state utility he worked for. He had to adapt to new schools and communities, an experience that prepared him for his peripatetic business career. “I still have a little bit of that nomad touch,” he says. “If I move on and start packing things, I get a little thrill.”

A keen sailor with a year-round tan, Mr Svanberg says he thrives on the teamwork of business in the same way he enjoys skippering a boat. He prefers to persuade rather than order. “If I have to say to someone, ‘I hear what you say, but I’m deciding and this is what we’re going to do,’ that feels like a poor way of going forward.”

After the Deepwater Horizon disaster, he called every BP board member every day for 100 days to keep them informed and solicit views. From this process came the decision to oust Tony Hayward, the chief executive who caused offence by telling reporters he wanted his “life back” from the demands of disaster response, even as families grieved for the 11 men who were killed in the rig explosion. He was replaced by Bob Dudley, the American who leads BP today.

Did Mr Hayward accept the need for change? “I think he intellectually understood it,” says Mr Svanberg. “I think emotionally he didn’t.”

There have been other moments of tension, such as a shareholder rebellion in 2016 over the 20 per cent pay rise for Mr Dudley despite BP suffering its worst annual loss. “We could have read that situation better,” admits Mr Svanberg.

Yet, for all the turbulence, the sailor will leave BP with his reputation enhanced for steering the company to calmer waters. “I didn’t think we would by now have come as far as we’ve done,” he says. “I feel very happy about that.”

Ask an outsider: damage control

“After any crisis, it is vital to have the right voice out there immediately and transparently, to tell the company’s story about what it knows and what it doesn’t know so far,” says Michael Watkins, professor of leadership and organisational Change at IMD business school, Switzerland, and author of “How BP Could Have Avoided Disaster”.

He says: “If you don’t do that and you are in a hole, a very deep hole, then you are in the brand recovery stage, and the damage has been done.” In that case, as happened to BP, the first thing to change is the leadership, as you cannot hope to rebalance a decent dynamic once the damage has been done, he adds. The new leadership needs to focus on getting right what went wrong.

The other priority, says Prof Watkins, is to ensure the crisis does not distract the leadership team from what they normally do. At these crisis points, companies are vulnerable to things going wrong because executives are distracted.

Nassia Matsa

Comments