China’s ‘sent-down’ youth

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Ma Shangzhu’s face lit up with a radiant smile as she leaned out of the train window and waved goodbye to her father. In a white blouse and plain cotton jacket with a plaque of Chairman Mao on her chest and two braids behind her ears, the 18-year-old from Shanghai looked expectantly into the distance. Today it is difficult to recognise the young woman with the eager smile in the wax-white, wrinkled face bent over that photograph from 45 years ago. “It was not like this,” says Ma, a petite woman who appears older than her 63 years. “You can’t tell from this picture what I felt that day.”

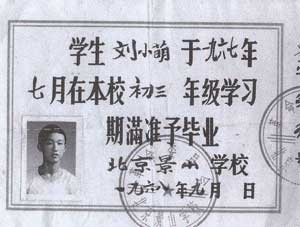

On September 17 1968, the train took Ma and 305 other students more than 2,000km from her middle school in Shanghai, to the wooded hills and deserted plains of China’s far northeast, close to the Russian border. They were among more than 17 million Chinese urban youths sent to the countryside to do hard labour on farms and in forests in the 1960s and 1970s.

“It is very necessary for the educated youth to go to the countryside and undergo re-education by the poor peasants,” declared Mao Zedong, the man who led China’s communist revolution in 1949, in a missive in December 1968. “We must persuade the cadres and others to send their sons and daughters who have graduated from elementary school, middle school and university to the countryside, let’s mobilise. The comrades in the countryside should welcome them.” With the start of the cultural revolution in 1966, schools all over the country closed. Many of the children who followed Mao’s rallying cry to “go up into the mountains and down to the countryside” ended their education after elementary school. The transfer engulfed about 10 per cent of China’s urban population.

Together with three comrades from the days on the farm, Ma has come to a quiet restaurant in the heart of Shanghai to talk about the past and explain how those years changed her life. They are memories shared by an entire generation, including several members of the country’s new political leadership. Xi Jinping, the party chief who became president this March and is expected to lead the country for the next 10 years, went to the poor northern Chinese province of Shaanxi when he was 15, less than a year after Ma left home. He only returned home to Beijing seven years later.

“Going up into the mountains and down to the countryside” was by no means Mao’s most murderous campaign. But it bears the trademark of Mao’s rule: a violent intrusion of a totalitarian state into people’s lives. For many, it amounted to outright deportation and imprisonment in labour camps, depriving an entire generation of their youth and ripping millions of families apart.

But in the Communist party’s official narrative, the hardship, loss and terror disappears behind tales of adventure and romance. In the party-controlled media’s reporting on Xi, those years made him a practical, thrifty person, sharpened his eye for the needs and concerns of the ordinary people and heightened his understanding of the country’s economy. Other official accounts praise the wonderful years the young people had amid nature and say that the movement formed an elite that became the backbone of the “New China”, a generation with a strong ability to endure hardship.

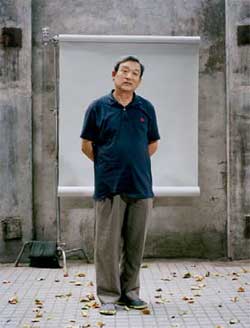

“From the perspective of a historian, from the perspective of the entire nation’s development, this period must of course be negated,” says Liu Xiaomeng, a history professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing and author of some of the most authoritative books on the subject. “This is a very dark era in the history of mankind.”

Although the Communist party has changed beyond recognition since Mao’s death, replacing constant political struggle with pragmatic pro-market policies and a retreat from people’s personal lives, it continues to resist an all-out reassessment of the decades of totalitarianism.

Liu is an authority on the “sent-down youth”, but he conducts his research as a hobby and faces obstacles in accessing first-hand sources on the subject. Official research in national archives on topics such as the “sent-down youth”, Mao’s disastrous “Great Leap Forward” campaign which caused an estimated 30 million deaths, and the cultural revolution, remains reserved for the party’s own internal historians.

“Contemporary history in China is not an academic subject,” says Liu. “Institutions like the Central Party School have a lot of so-called research on contemporary history, but it lacks independence and academic rigour.” Much of his groundbreaking research was completed with the help of former students who work in archives and gave him access to files as a favour.

But as the former “educated youths” have started retiring over the past decade, they have found the time to think about their own memories. China’s 35 years of economic growth have left many of them with enough money to revisit the places where they spent their youth, and the country’s booming internet has given them the means to tap unofficial sources for history and to reconnect with others that shared their fate.

Many have set up web forums to exchange old photographs and formed groups to travel to the farms and villages. Ma and her three Shanghai friends all spent several years in Tieli, a county 200km from the Russian border at camps run by the bingtuan, a paramilitary force set up to develop agriculture and forestry in remote border regions. They now have their own website, and have organised several reunions.

While they order food, they start reminiscing about the endless sky, the clear streams, the block houses they built with their own hands and evenings full of song and laughter. “We went voluntarily,” says Cao Yifei, a friend of Ma’s who pats her arm every now and then as if to encourage her. The first 306 students from their Shanghai school left three months before Mao’s December 1968 directive. After that, it would become almost impossible to refuse.

Bao Danru, the recently retired former deputy head of the Shanghai municipal labour bureau, recalls how, aged 16, he signed up to go to the northeast without telling his parents. “I took our household registration booklet from the drawer and transferred my registration from Shanghai to Heilongjiang province, and only when the notice came that I’d been approved did I tell my parents – three days before I was scheduled to get on the train. It was too late for them to say anything.”

Two years ago, the Tieli group published a book with hundreds of pictures and nostalgic verses. During the meal, Cao shows me some of the photos. There is Bao, young and upright, a tractor driver. There is Gu Yaoqi, now a thin elderly man but then the most handsome of the gang, giggle the two women. And then there is the photo of Ma on the train. Cao praises her beauty but her friend starts swallowing hard. “That day, you can’t see in the picture how hard it was for me,” she says with a shiver. “We went voluntarily but the reasons were complicated.”

Ma came from a “bad family”. Both her parents were attacked in the cultural revolution as counter-revolutionaries, and their home was raided by Red Guards. “My family was struggling to survive. The main reason I signed up was because on the farm I would have a wage, and I would be less of a burden to my family,” she says, now crying. Such troubles were very common. Even Xi Jinping was in a similar situation – when he left home, his father, a veteran revolutionary leader, had just been imprisoned.

She recalls that she was close to breaking down when her father saw her off. “My father was crying, and all I kept thinking was not to look my father in the eye because I knew I would break down in tears as well.” It would be three years before she would be allowed to visit home. On that trip, she and her mother sat face to face crying silently for more than half an hour.

Cao also speaks out. “What I regret most is that I didn’t get an education. I could have gone to university if we hadn’t gone there,” she says. “There is a best age for studying, and we missed it. I had no opportunities there, none.” Cao only returned to Shanghai in 1979 when her father’s retirement freed up his job at a state-owned textile plant.

A lively woman with big, warm eyes in an open face, Cao is also tormented by the thought that she may have increased her parents’ suffering. Like Ma’s family, Cao’s mother was attacked in the cultural revolution. She died soon after Cao’s return home. “I keep thinking I could have taken care of her if I’d been there. She might have lived longer,” she says.

The two women launch into tales of the Great Northern Wilderness. In 1969, when the region suffered torrential rains, their clothes would not dry for weeks. “Our trousers were so dirty that they could stand on their own. In the morning, we would slide into the same cold, damp pair of trousers as the night before,” recalls Cao.

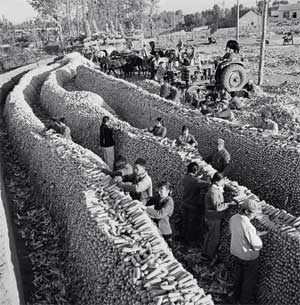

Gu tells of the long days during the harvest. “The fields in the northeast are so huge, they stretch on over the horizon,” he says. “You walk straight all day harvesting one row of soya beans, and you won’t even reach the end at night.” The young workers would drink from the tracks horse carts had left in the mud. Many fell ill with cholera. When leaving the block house in the morning, Gu Yaoqi would step into faeces from people who had hurriedly relieved themselves overnight just outside.

…

The growing body of documentation put together on the initiative of former “educated youths” shows that much worse things happened. Another group of Shanghainese who spent part of their youth in the northeast have built an educated youth museum on the south bank of the Amur river that forms the border between China and Russia.

Its avant-garde building, a bright red triangle, sits amid a smattering of low brick houses in sunny little gardens. But inside, pictures on the walls of a dark cavernous room tell the horrific stories of those who did not come back: a boy who died in solitary confinement after political criticism sessions; a girl who did not receive her mother’s last loving letter as she succumbed to her injuries after being raped. Many more who died of malnutrition, the cold or in accidents.

The museum does not offer any political comment. Similarly, the booklet published by Bao and his comrades has a chapter on those who died in Tieli, but there is little more than their pictures with a few lines of remembrance. “Judging this period in history is very complicated,” says Bao. “We don’t take a position. What we talk about are our memories, this is about our youth.”

Not all former “sent-down youth” are that sanguine. Feng Gejie, a 61-year-old from the northeastern province of Heilongjiang, laboured on a state farm for a decade and is still full of anger about a system that he believes wrecked his life. “Our generation has been wasted,” he says. He describes his time on the farm as one long stretch of imprisonment, and he was continually subjected to political struggle sessions. Mass meetings where people had to criticise their fellow students, neighbours and colleagues were one of the main strategies with which Mao ruled the country. Humiliations and physical violence were common, and many were beaten to death or driven to suicide. “Of course, the landscape was beautiful, especially in summer, when the fields would stretch further than you could see and the wheat looked like waves,” says Feng. “But I felt like I was living in a golden pigsty. There was no freedom, no dignity.”

He looks down on those who have nostalgic feelings about their time in the countryside. But historians feel encouraged that the “educated youth” generation is claiming back its own past. “It is a positive sign that there is a space emerging for private memories outside the party’s interpretation of history,” says Nora Sausmikat, a German sinologist who has researched how China deals with history. “In that process, it is natural to see multiple, conflicting narratives.”

…

There are signs that an increasing number of this generation are taking a more critical look at their youth and the political forces that shaped it. Several former Red Guards, those who followed Mao’s rallying cry to destroy China’s traditional culture and build a new socialist society, have publicly apologised during the past few months for turning against their teachers, cadres and even their own families. But this remains an exception.

Many Chinese don’t want to hear about their ugly recent history. The sufferings imposed by their political leaders in a seemingly endless series of murderous mass campaigns has left many of them with such deep fear of luan, or chaos, that they support the Communist party in its insistence that the past be left alone.

“At the time we didn’t know that the cultural revolution was wrong, that going up into the mountains and down to the countryside was wrong,” says Wu Shuibin, a retired school principal from Harbin. She has met us at a coffee house to tell about her years on a bingtuan farm. “We all thought that life was like this, back then we were really stupid, we didn’t know. We didn’t know anything,” she says with a shudder. “That was the torrent of the times, you couldn’t resist it. We have to let history judge.”

The party’s sharp break with Mao’s leadership style appears to only feed amnesia. Some of the excesses of the Mao era seem unthinkable to those born after the start of the reforms. “I feel that there is an insurmountable divide between my generation’s experience and that of our children,” says Cao. “The gap is much bigger than between me and my parents’ generation.”

The Communist party has made little progress in allowing public debate of the past. The fact that the party ordered troops to turn on its own citizens in the 1989 democracy movement remains taboo. And with propaganda slogans that revive and sometimes glorify Mao Zedong, the new leadership under Xi Jinping suggests that there is little hope for a re-evaluation of the dictator’s record.

But critics believe that in the long term, China cannot avoid an open debate of recent history if the country wants to be at peace with the world and itself. Yuan Weishi, a retired history professor, wrote years ago that the country’s youth was being “raised on wolf’s milk”, warning that the party’s ideology-soaked narrative was breeding nationalism. Says Liu: “I try to do my part to tell people, especially the young, a bit more about the historical truth.”

Kathrin Hille is the FT’s Beijing correspondent. Additional reporting by Zhao Tianqi. To comment, please email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments