Luxembourg space programme to work with Nasa on moon mining

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Luxembourg first emerged as a potential space power five years ago. In February 2016, the Grand Duchy launched its Space Resources programme, a project to prepare for the future use of extraterrestrial minerals, water and gases to provide energy and materials for human activities beyond Earth.

Initially the international media presented a vision of little Luxembourg setting out to mine asteroids, in a tone somewhere between awe and scepticism — encouraged by talk of partnerships between the Grand Duchy and two US asteroid mining ventures. Since then, the prospect of asteroid mining has receded, while the moon looms larger as a destination.

“There was perhaps a little misconception about asteroid mining at the beginning,” says Marc Serres, chief executive of the Luxembourg Space Agency. “Today the international enthusiasm for sending people back to the moon presents a fantastic opportunity for space resources.”

Nasa is leading an international programme called Artemis which aims to return people to the moon in 2024. Initially astronauts will make short visits to the lunar surface, but the US space agency plans “an incremental build-up of infrastructure on the surface later this decade, allowing for longer surface expeditions with more crew”.

Luxembourg aims to play a part, providing the inhabitants of Artemis Base Camp with the ability to search for resources and process them into materials such as oxygen and fuel, which will be required for long-term human habitation on the moon.

Serres points out that a Luxembourg company, iSpace Europe, won a Nasa contract in December to collect soil and rock from the lunar south pole with a robotic lander in 2023, as part of an unmanned Artemis demonstration programme ahead of the crewed landings.

A related development in November was an agreement with the European Space Agency (ESA) to set up the European Space Resources Innovation Centre in Luxembourg. Esric will be established over the next couple of years as a research and development hub, drawing in public and private funding.

One element of Luxembourg’s role in global space activities is contributing to the legal frameworks that govern them. Last October, the Grand Duchy became a founding member of the Artemis Accords, which will guide future international co-operation in space, alongside the US and six other nations.

The accords reinforce and implement the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which was drawn up under the auspices of the UN. Their principles commit Artemis participants to use space solely for peaceful purposes, while recognising that extracting and exploiting extraterrestrial resources is key to safe and sustainable exploration of the solar system.

In the long run, Serres says, international space law should be reformed to take account of developments since the Outer Space Treaty came into effect 54 years ago, with its landmark declaration: “The moon and other celestial bodies . . . shall be the province of all mankind.”

Back then, the idea of companies exploiting space resources was science fiction. Though the treaty forbids national expropriation of territory on celestial bodies, it provides no clarity over whether commercial mining and manufacturing are permitted there.

But Serres is not optimistic about quick progress. “Revision of existing treaties may take a long time,” he says. “I am wondering whether this is a realistic approach today.”

Meanwhile Luxembourg is strengthening its national space law. In 2017 it became the first European country — and the second in the world after the US — to provide a legal framework for companies based there to exploit resources in outer space. This was supplemented by further legislation passed by Luxembourg’s Parliament in December 2020.

About 50 space companies are already active in Luxembourg, Serres says, and he expects that number to grow as businesses are attracted to the Grand Duchy through financial incentives and the appeal of being part of a growing space cluster.

“We are trying to encourage a different and more entrepreneurial way of thinking about the business of space,” Serres says. “There are a number of companies that just go from one ESA contract to the next. That is not what we want. Although ESA is an extremely important partner, we see it more as a supporter than a customer.”

Luxembourg has developed a variety of ways to support the country’s space businesses. Last year it invested with public and private sector partners in Orbital Ventures, a €70m fund that supports commercial space start-ups.

The European Investment Bank is another source of funds for space companies in Luxembourg. In December the EIB announced a €20m financing agreement for Spire Global, to help it develop a constellation of small Earth-observing satellites and expand its space data business.

Luxembourg’s first and largest space company, the satellite broadcaster SES, founded in 1985, does not manufacture its large satellites in the Grand Duchy, though it develops control software and runs a testing and integration lab there.

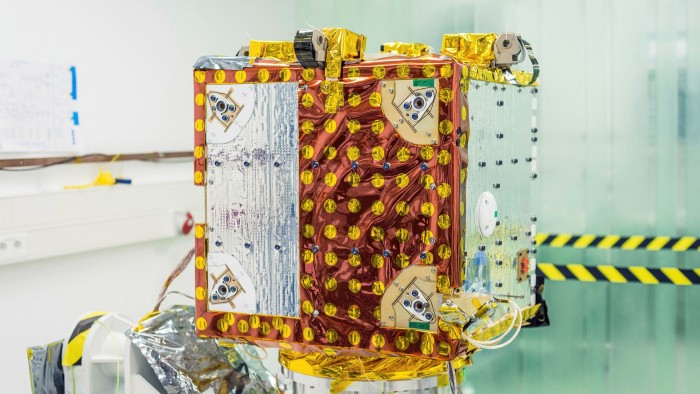

However, Luxembourg is beginning to produce microsatellites. One, made by LuxSpace and called Esail, was launched in September to track ships across the world’s oceans by detecting the radio messages that their automatic identification systems emit. It will provide data to the European Maritime Safety Agency for monitoring global shipping movements.

None of these activities has to pay off quickly. Luxembourg is taking a long-term view. “Our primary driver is to diversify our economy through space activities,” says Serres.

This would represent a third wave of development. From the 1870s Luxembourg began to establish a world-class steel industry, the main source of the country’s growing wealth for almost 100 years until it collapsed during the structural crises that engulfed the world’s steel companies in the 1970s.

Financial services propelled the next growth phase, but as that sector continues to face questions about transparency and tax dodging, Luxembourg’s leaders envisage that growth period slowing, too. Innovative science-based industry — and space in particular — is seen as the propellant for continued prosperity into the late 21st century, as humanity moves out into the solar system.

Do not dismiss the idea of a Luxembourger landing on the moon — or even Mars — some time in the future.

This story is part of a special report Luxembourg: Data and Innovation.

Comments