Artists get carte blanche at São Paulo Biennial

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro is a man on a mission to turn the biennial model on its head. These supersized contemporary art events have mushroomed across the world: there were 320 biennials or similar events at the last count, from the oldest example in Venice to younger contenders in Riga and Bangkok. But are they sustainable?

As chief curator of the 33rd São Paulo Biennial, which opened earlier this month, Pérez-Barreiro invited seven “artist-curators” to conceive group shows, giving them carte blanche to choose whomever they like. Each artist also had to include his or her own works, according to Pérez-Barreiro’s terms.

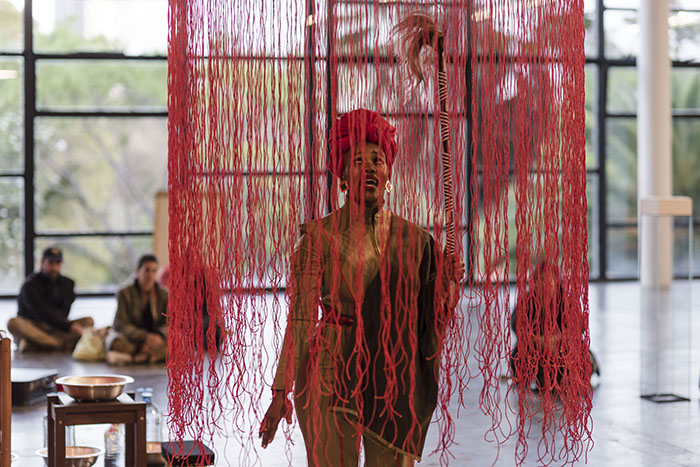

His artist-curators include the established Swedish artist Mamma Andersson and UK-based Claudia Fontes. Andersson’s intriguing selection features the late US artist Henry Darger, a reclusive hospital janitor who led a double life as a prolific artist and novelist. Fontes’ stable encompasses the UK film-maker Ben Rivers and Katrín Sigurdardóttir of Iceland. Other artist-curators are the Brazilian sculptor Waltércio Caldas, Alejandro Cesarco of Uruguay and Lagos-based Wura-Natasha Ogunji.

By handing over the reins to these artists, Pérez-Barreiro aims to disrupt structural hierarchies in the art world. His target is “curatorialism”, an approach that started to dominate in the 1980s when “the curator began to emerge as the centre of the contemporary art system”, he says.

Other biennials are also reworking the traditional blueprint; the 12th edition of the Gwangju Biennale, Imagined Borders, for instance, has 11 international curators at the helm.

In São Paulo, the artists definitely appear to be in control. The seven have created their own shows, rather than adhering to a rigid brief set by curators. Pérez-Barreiro’s model should, he believes, enable themes to emerge organically and allow artists to understand their own practices better.

The biennial model is certainly in need of reform. Pérez-Barreiro is damning of the “social frivolity of the opening events for the art world élite, and the increasingly dense theoretical framework of their curatorial statements”. But he falls into traps of his own making. Each artist-curator has, for instance, released an explanatory statement detailing their vision. Sofia Borges’ exhibition is entitled The infinite history of things or the end of the tragedy of one, and although her group show brims with clever, original works, such as Jennifer Tee’s ceramic and bamboo balancing sculptures (“Spirit Matter”, 2013), Borges’ curatorial notes, which talk about “infinity” and “a beautiful fire”, are unfathomable.

There is also good reason why artists are artists and why curators are appointed to edit and shape their output. The artist’s gaze is different from the curator’s, and it is not always easily understood. Caldas’ presentation, for instance — which combines works by José Resende, Bruce Nauman and Richard Hamilton — is patchy and feels soulless.

Some of the other group shows are fluid and interesting. Andersson throws a light on overlooked names, such as Carl Fredrik Hill, the Swedish painter who suffered a breakdown aged 28 and died in 1911, at the age of 62. Ladislas Starewitch’s stop-motion animation featuring humanoid insects painting and fighting (“La Revanche du Ciné-opérateur”, 1912) is also a revelation.

Claudia Fontes explains, meanwhile, that her point of departure “was to think about the possibilities of existence of a slow bird, an ambiguous fictional creature, almost an oxymoron in itself, that could be interpreted in different ways by each artist.” Certainly, her selection prompts the viewer to slow down and take stock in a tumultuous world. One example is Ben Rivers’ film You Can’t Imagine Nothing (2018), which focuses on a sloth lolling in shrubbery.

Fontes’ artists, she says, “are accessible at a direct, perceptual level, before intellectual understanding interferes in their appreciation.” This chimes with Pérez-Barreiro’s wider ambitions for the Biennial, which is called Affective Affinities — a title rather than a guiding theme, he stresses. His ideas are informed by the writings of Mário Pedrosa, the 20th-century Brazilian art critic and political activist. Pedrosa, he explains, “articulated a profoundly humanist perspective through which to understand art”, a view that can be summed up as: ignore prevailing theories and refocus on the experience of savouring art.

The most enjoyable aspect of the Biennial is the 12 solo installations and exhibitions curated by Pérez-Barreiro, which accompany the artist-curator interventions dotted around the huge Pavilhão Ciccillo Matarazzo in the palm-tree-lined Ibirapuera Park.

This cavernous arena, designed by the great Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, dwarfs everything and everyone, and must surely intimidate curators and artists. But some of these solo shows are exceptional; installations by Lucia Nogueira, a Brazilian artist who died in 1998, incorporate everyday items such as plastic bags and crates to both witty and unsettling effect. Even a single soda can on a pedestal (“Refrain”, 1991-8) is affecting here at the Biennial.

Another special exhibition presents the exquisitely embroidered fabrics and pillows made by the late Paraguayan artist Feliciano Centurión following his HIV diagnosis. He died in 1996 but these poignant memorials, often stitched with a single word such as “Reposa” (rest), ensure his legacy endures in São Paulo and create more of an impact than many of the contemporary pieces on display.

These solo projects give the Biennial substance, providing a coda to the seven artist-curator displays. Overall this is a flawed but important experiment; any attempts to make today’s bloated biennials more digestible deserve praise.

To December 9, bienal.org.br

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments