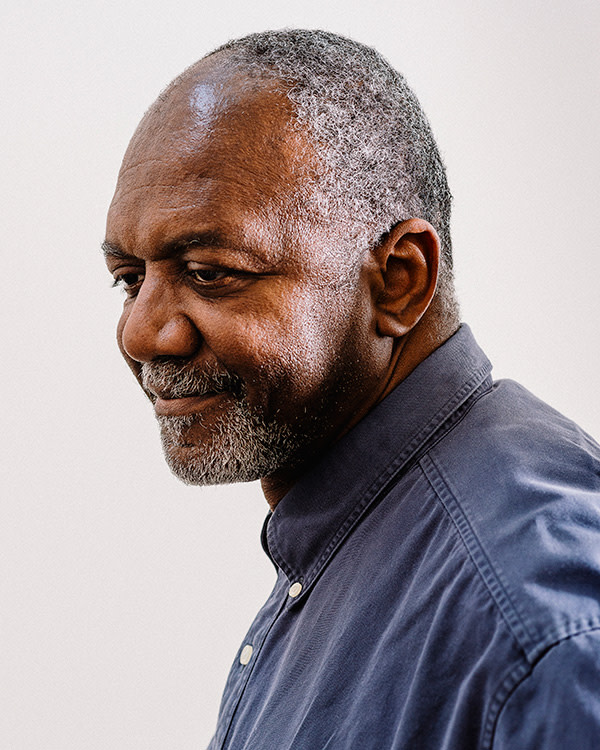

Kerry James Marshall, Chicago’s art star

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

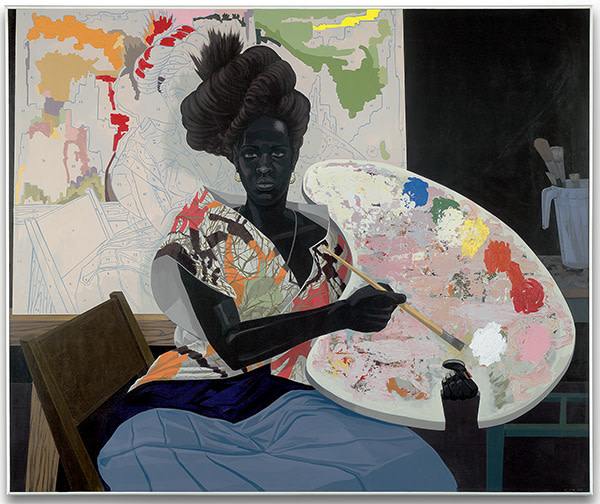

On a blustery morning in March, Kerry James Marshall, in a bright- green, long-sleeved T-shirt, took the podium at the Met Breuer, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new contemporary outpost in the former Whitney Museum in New York, to tell a gathering of art critics and writers getting a sneak peek how it felt finally to be a part of what he termed “the club”. Upstairs, an untitled 2009 canvas from his Painters series was hanging prominently in the museum’s inaugural group show. The work features an ebony-skinned female artist holding a palette and gazing assuredly at the viewer. Behind her is a paint-by-numbers self-portrait in which the figure has yet to be filled in. The artist’s brush hovers over a large dab of white paint on the palette, which is curiously free of black pigment, leaving viewers in suspense as to how she will choose to represent herself. The painting seems to ask both “Who gets to create?” and “Who gets to be the subject of a painting?”

Beaming, Marshall was visibly moved by the moment. “[Artists] go to museums like the Met,” he said. “But at a certain point, just coming to the museum to see what other people do in those spaces is unacceptable . . . For me, it had always been my ambition to be in among the works that I came to the museum to look [at] . . . I can’t say enough how meaningful it is for me to finally get a chance to be in the Met as opposed to just coming to the Met . . . I can finally say now that I have been in an exhibition with Leonardo da Vinci.”

Marshall was ostensibly speaking for all artists wanting to belong but it was impossible not to pick up on the subtext that, as an African-American, his initiation was overdue. The next morning, over breakfast at a midtown Manhattan hotel, he wryly notes that “Museums for generations have done quite well without a lot of black images or black participation.” For more than 35 years, he has used his brush to help rectify that imbalance, creating a body of work that reimagines the traditions of western art history — from genre and history paintings to nudes, portraits and landscapes — with black men and women. “I want them to find a place in a world that is not looking for them.”

At 60, Marshall has become one of the most admired artists of his generation. Later this month, a major retrospective of his work will open at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago before travelling to the Met Breuer in the autumn and then to the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles next year. “I have been wanting to do this show since I met Kerry in 1993,” says Madeleine Grynsztejn, director of the MCA Chicago, adding that the exhibition is particularly pertinent in 2016. “When we are seeing the concluding chapter of a black presidency, the emergence of Black Lives Matter [the campaign protesting violence against blacks that began after the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012] and increasing attention brought to social inequality and social injustice, the work Kerry has done for 35 years has an additional relevant cast. It is a profound meditation on some of the most important issues we face.”

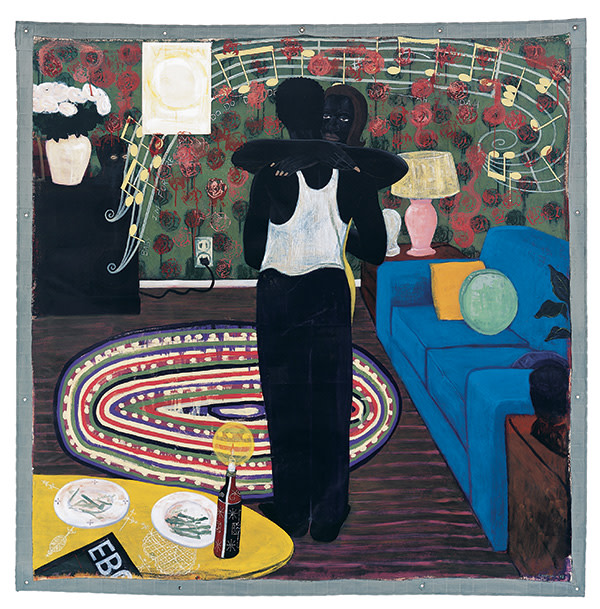

Marshall’s paintings incorporate the imagery of African-American experience, from slave ships and the freedom fighter Nat Turner to the everyday lives of contemporary blacks — on dates, at picnics, getting their hair done — often in his own troubled neighbourhood of Bronzeville on Chicago’s South Side. His signature palette of red, black and green mirrors the Pan-African flag. His compositions are complex, the humanity and emotion palpable. They not only “course-correct” the canon, Grynsztejn says, but are also “drop-dead gorgeous.”

Marshall is an interesting blend of sincere gratitude — he remembers the name of every teacher who ever offered a modicum of encouragement — and well-earned confidence. “I belong anywhere I am,” he says. “Because I think I know a thing or two about what I’m doing, I don’t think there’s anyplace where the people I encounter will know more about it.”

. . .

Marshall can pinpoint the exact moment he decided to become an artist. He was in kindergarten, at the Roman Catholic Holy Family school in Birmingham, Alabama. His teacher, the only black lay teacher among a sea of white nuns and priests, kept a scrapbook of pictures cut from Christmas cards and magazines such as the National Geographic. When a child was especially well-behaved, the reward was to page through the scrapbook. “The day I got to look at the scrapbook really was the day that changed my whole life,” Marshall says. “It seems inconceivable that it can be so clear, but I can remember at that time saying to myself, ‘I want to make pictures like these.’ I’ve never wanted to do anything else from that day. I didn’t know it was called an artist, but I knew I wanted to make pictures that could do for other people what those pictures were doing for me, which was to transport you to a place so unlike the world you were in.”

Though his family was not Catholic, the religion’s rich visual culture, from stained-glass windows to the pageantry of the mass, mesmerised him. “You’ve got the priest in those robes, all the boys in that white thing [he means a surplice],” he says in awed tones, as if recalling a sumptuous meal. “You’ve got the person swinging the incense ball, the kid with the candle snuffer. The whole ceremony — it was magic.” He became fixated on rosaries — not as religious symbols but as objects — and would pick up broken ones and reassemble them at home.

Marshall’s family was working-class — his father was a dishwasher at the Veterans Administration Hospital — and aspired to the more middle-class life of his mother’s sister, a nurse whose family lived across the street. In 1963, when he was eight, the Marshalls joined the Great Migration, the movement of millions of black Americans that took place between the first world war and 1970 from the predominantly rural south to the increasingly urban north and west. Marshall’s father made the journey to Los Angeles first, finding work in the kitchen of a VA hospital, and an apartment in Nickerson Gardens, a public housing project on the edge of Watts in South Central LA.

In some ways, Los Angeles was markedly different. “The light seemed to hurt our eyes. Our eyes were burning,” Marshall recalls. But it wasn’t the sun — “It was smog.” In other ways, their lives were surprisingly the same. Another of his mother’s sisters and her family moved to LA at the same time, and yet another sister was already living there. The city was quickly becoming home to old friends and neighbours from Birmingham. “We moved from one neighbourhood in Birmingham that was all black, to Watts, which was all black. So it was the same kind of people.”

In 1964, a year before riots erupted in Watts, the Marshalls rented a house further north in South Central. At the elementary school there, Marshall stayed on at the end of the day to help his teacher; she reciprocated by teaching him how to paint flowers. His biggest artistic influence, though, was Jon Gnagy, whose popular TV show Learn to Draw instructed viewers to focus on the shapes of objects, not the outlines. Marshall watched faithfully, pencil and paper at the ready — and learnt that making pictures “wasn’t magic. It was knowledge. It wasn’t even talent, really, as much as it was knowledge.”

When he was about 10 years old, Marshall went on a school field trip to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Not only had he never been to a museum before, he’d never even heard of such a thing. “The term ‘museum’ had never entered my consciousness,” he says. “Going into that building and seeing all those pictures, the sculpture, from all over the world, it was a revelation.”

His seventh-grade art teacher recommended him for a drawing class at the Otis Art Institute in LA. Once he learnt the African-American social realist painter Charles White was still teaching there — “I thought he was dead because he was in a history book” — Marshall had one goal: to attend Otis full time after high school. Because that required two years of college credits, he worked a series of blue-collar jobs, fitting in art classes when he could. When he finally began at Otis in January 1977, aged 21, he was the only black undergraduate there.

By the late 1970s, the college was overrun with conceptual artists, and Marshall describes an “active antagonism” between them and the more skills-oriented painters and sculptors. Painting may have been “dead,” but Marshall was unwilling to surrender his lifelong ambition. “The way I looked at it was, I can always get somebody to fabricate something for me,” he says. “But if I want to make a painting and I don’t know how to do it, I can’t fake it. If I didn’t learn how to do that well, I would always be dissatisfied. I would feel like a failure.”

Yet another obstacle was that within painting circles, abstraction was dominant. Many black artists in particular were pro-abstraction, hoping the absence of the figure would put them on an equal footing with white artists. Marshall was fiercely determined to paint the figure — and more precisely, the black figure. “The answer to the lack of black figure representation in painting is not abandoning the figure and moving toward abstraction; it is more figure representation. That’s the antidote,” he explains. “The antidote is more of it, so that it becomes so common that it’s no longer exceptional to see black figures in pictures when you go to the museum.”

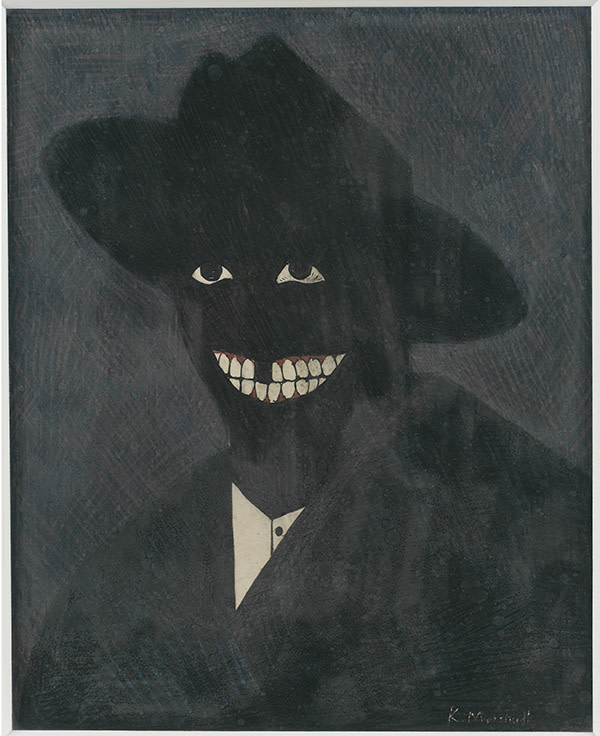

A breakthrough came when Marshall read Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, about a black man’s metaphorical invisibility in white America. Despite the book’s critical acclaim, Marshall wasn’t familiar with it but, as a science-fiction buff, he was a fan of HG Wells’s much earlier novella The Invisible Man, about a man becoming literally invisible. “Something clicked,” he says, when he contemplated the two types of invisibility. “That really launched the whole exploration, this dilemma of visibility, invisibility: presence and absence. The challenge became, how do you render this blackness that is both present and absent at the same time? I started out with that first figure as a silhouette, as a shadow.”

Marshall painted a series of powerful black-on-black paintings, beginning with “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self”(1980), in which only the whites of his eyes, teeth and shirt and the red of his gums contrast with his jet-black skin. The challenge was to achieve definition and volume without lightening the pure black skin tone he desired. The solution was, initially, a restrained white line and then, the discovery of slightly different black paints, such as iron oxide black and carbon black. He eventually devised seven variations of black.

In 1985, Marshall landed a residency in New York at the Studio Museum in Harlem. He packed his possessions in a Volkswagen van and drove cross-country. The first person he met there was Cheryl Lynn Bruce, an actor whose day job was in public relations for the museum. They soon became romantically involved and, when his residency was over, instead of staying in New York as he had planned, he followed Bruce back to her hometown, Chicago. Before they married, Marshall rented a 6ft by 9ft room at the YMCA on the South Side. “I would stand on the bed and put a canvas on the wall,” he says. “I never stopped working, was the thing.”

On his first day in the city he found a job with a moving company by looking through the phone book and cold calling “places that did things I knew I could do”. The company’s headquarters was on the North Side of the city, and one day he happened upon a thrift shop selling books for five cents. “So I started buying tons of Harlequin romance novels, he says. He tore off the covers and used them as collage elements in paintings. With titles such as “Dark and Lovely” and “Stigma Stigmata”, Marshall’s treatments pointedly contrasted the books’ all-white cover girls with his black portraits.

He made the most of wherever he lived. For “The Face of Nat Turner Appeared in a Water Stain (Image Enhanced)” (1990), he painted on a wooden desk-top abandoned behind his apartment building. He also produced a group of paintings that earned him a $20,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, which he used to rent a real studio. “That’s when the work went from what I could do in an apartment or the Y, up to those ceiling heights,” he says. “That studio had 12ft ceilings, so I did some 12ft-high paintings. Everything changed after that, literally, because I could work freely at a size that I wanted to. The work assumed a level of complexity that I wanted.”

He soon painted “De Style” (1993), a sprawling barbershop scene of young people and their gravity-defying hairstyles. LACMA, the first museum he’d ever visited, promptly bought it — his first acquisition by a museum.

. . .

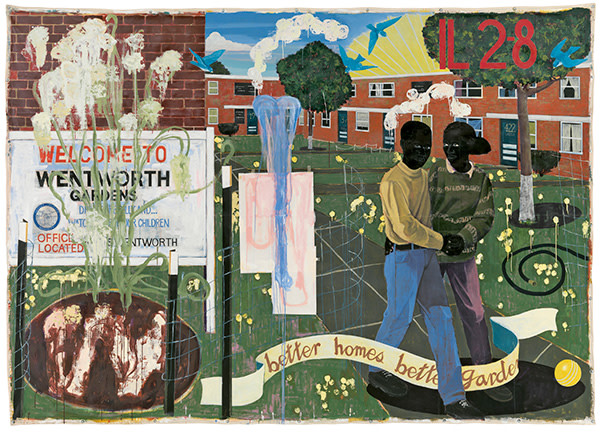

Chicago proved to be a place where Marshall could keep his head down and work. “There’s a gallery scene, there are great museums, but there’s not the kind of desperation or competitive feeling you get in New York,” he says. “Nobody really cared. You could do your stuff in Chicago, but nobody was really paying a whole lot of attention.” The city itself became a catalyst for Marshall’s art. His series of paintings, Garden Project (1994-95), came directly from his daily life in Bronzeville. He and Bruce had bought a house near Stateway Gardens and Wentworth Gardens, two notoriously violent, crime-ridden housing projects. “There were always attempts to make them more desirable, safer places to live,” Marshall says. “[But] all of those attempts seemed to fail.”

He remembered his childhood home at Nickerson Gardens as “wonderful” and began to think about how the conditions at such projects had deteriorated to the point of making cruel mockeries of their names. “I wanted to recover some of that pastoral idea of the garden and demonstrate that even though there was all this despair in the projects, there were still people having a good time. I mean, no matter how violent the projects, you could go by and there would be a birthday party out on the lawn. People find a way to get some pleasure in their lives in spite of the environment they’re in. I wanted to show they’re not totally hopeless.”

Marshall painted five monumental images of the projects, with figures happily strolling, playing and gardening beside welcome signs and green lawns. There are blue skies and birds carrying a ribbon in their beaks proclaiming, “Bless Our Happy Home”. There are also boarded-up windows and unsettling statistics in small print — including the fact that one Chicago project was 93 per cent African-American.

In 1997, Marshall was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, nicknamed the “genius grant”, a generous six-figure sum. He has been represented by the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York since 1993, and since 2014 by the David Zwirner Gallery in London. A new Marshall canvas can sell for $1m, and there is a waiting list. Marshall could easily afford to move to a more affluent part of town, but he and Bruce have decided to stay put, and he has made Bronzeville central to his paintings. “Some of them are set in my yard, on my porch,” he says. “You’ve got to show people that you can make beautiful things where they are, as opposed to the common idea for people in impoverished neighbourhoods that if you get a few dollars, you get out of there as fast as you can. Then, the collapse of the neighbourhood becomes inevitable.”

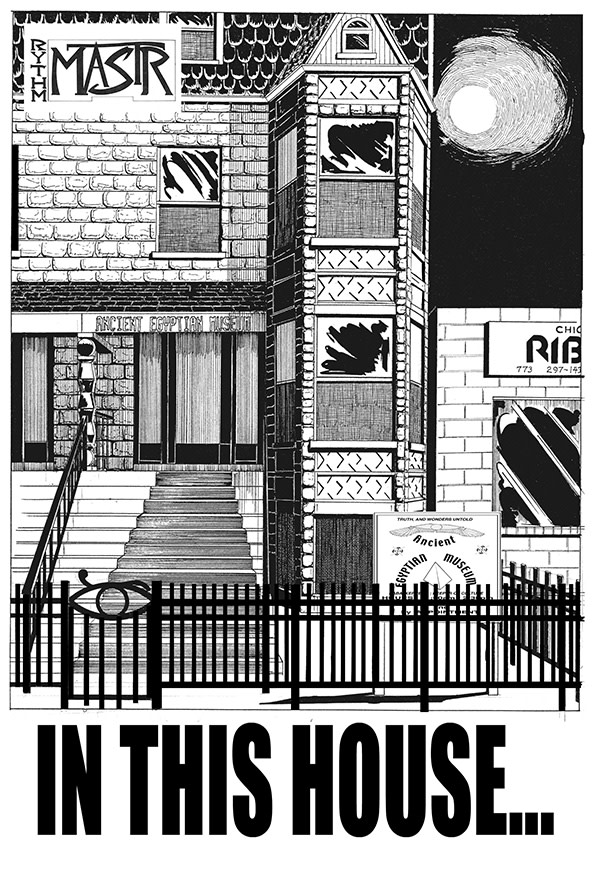

As the worst of Chicago’s projects, including Stateway Gardens, were demolished in the early 21st century, Marshall turned his attention to the persistent attempts by black people to connect to their African heritage. Down the street from his studio was a house with a sign in front that proclaimed it to be an Ancient Egyptian museum. “For black people, the apex of historical black culture is Egypt,” says Marshall. So he offered them a new mythology in the form of his comic-book hero Rythm Mastr, who resides in the museum. Bronzeville provides the backdrop for the ongoing action.

With Rythm Mastr, Marshall’s working process began to evolve. He had relied on photographs — his own and others’ — as source material. But he wasn’t satisfied with the first version of “Rythm Mastr” in 1999. Photos were just too limiting for the comics. Marshall, who had been production designer for the 1991 film Daughters of the Dust (the first US feature film to be directed by an African-American woman, Julie Dash), decided to approach the making of drawings like a movie set: in place of live actors, he posed GI Joe and Barbie dolls. “I can see them from every angle, as opposed to a privileged angle of a photograph,” he explains. To make sure that their clothing was original, he bought a sewing machine and learned to sew. He also began building precisely scaled sets in his studio.

“I’m obsessed with everything that I’m doing being 100 per cent invented,” he says. “Most black people who make work, outside the music industry, get no credit for being inventors of anything.”

That fear of being denied has energised but not defined Marshall. He is “hyperaware” that the imbalance of wealth and power in America means cultural institutions have been founded almost exclusively by whites. It follows that collectors, curators and dealers are predominantly white. “The art world is a funny place,” he says. “You don’t really feel racism per se at the art schools, but there is a way in which you are conditioned, as a part of a minority group that is always seeking equality, to try to appeal to the interests of the dominant authorities. That’s almost automatic.”

Marshall says he has learnt to be his own most important critic. “When I’m in the studio working, I’m only thinking, can I get it right? I never expected anybody to want to buy anything,” he says, adding with a chuckle, “I still don’t.”

‘Kerry James Marshall: Mastry’ is at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, from April 23 to September 25; then travels to the Met Breuer, New York; and the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles; mcachicago.org

Photographs: Lyndon French

© 2015, courtesy of The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago; © 2009 Kerry James Marshall. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago; © Kerry James Marshall. Photo courtesy of the DENVER art museum ; © MCA Chicago; © 2015 Museum Associates/LACMA. Licensed by Art Resource, New York; Courtesy of the artist

Comments