Notes from the castle: ancient and modern find harmony in a spectacular Scottish seat

Simply sign up to the House & Home myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Airlie Castle sits perched above a deep gorge where the rivers Isla and Melgam meet. Built in Angus in the north-east of Scotland by the Ogilvy family in 1432, it was constructed as a fortification; the river essentially works as a moat, wrapping itself around the base of a vertiginous drop. Only one vast wall remains from the original castle that was burnt down in 1640. A mansion was built on the site of the ruin in the late 18th century, and added to over time, creating an L-shaped structure along the cliff.

Airlie is the Scottish home of London-born artist Tarka Kings and her husband, the Scottish-American singer-songwriter and heir David Ogilvy, who divide their time between here and an airy, open-plan home in London, which they share with their three sons. The castle comes freighted with the weight of David’s family history. But the pair have managed successfully to marry their deeply different stories through their shared creative gifts.

The drama and beauty of this house come from its aspects. Recessed windows set into the thick brick walls at the back overlook the sheer drop down to the treetops that blanket the rushing waters in the Den of Airlie, an area designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest for its rare flora and lichens. From the front, views over a grassy terrace lead up towards a wooded expanse of oaks, alders, Scots pines and willows through a valley and out towards Glen Isla. A walled garden, thought to have been built in 1790, is host to magnificent topiary hedges planted by the 7th Countess of Airlie in the late 19th century. Tarka and David have taken advantage of its protective shelter to create a grass tennis court. Inside, the house feels surprisingly intimate, thanks in part to it being only one room deep, which fills it with light from windows on either side of the building. Its four floors are connected by two winding stone staircases and the top of the house opens into a warren of cosy prewar‑style attic rooms – decorated with colourful rag rugs strewn over white floorboards and wrought-iron beds, each covered with a vintage checked blanket – for the children and their friends.

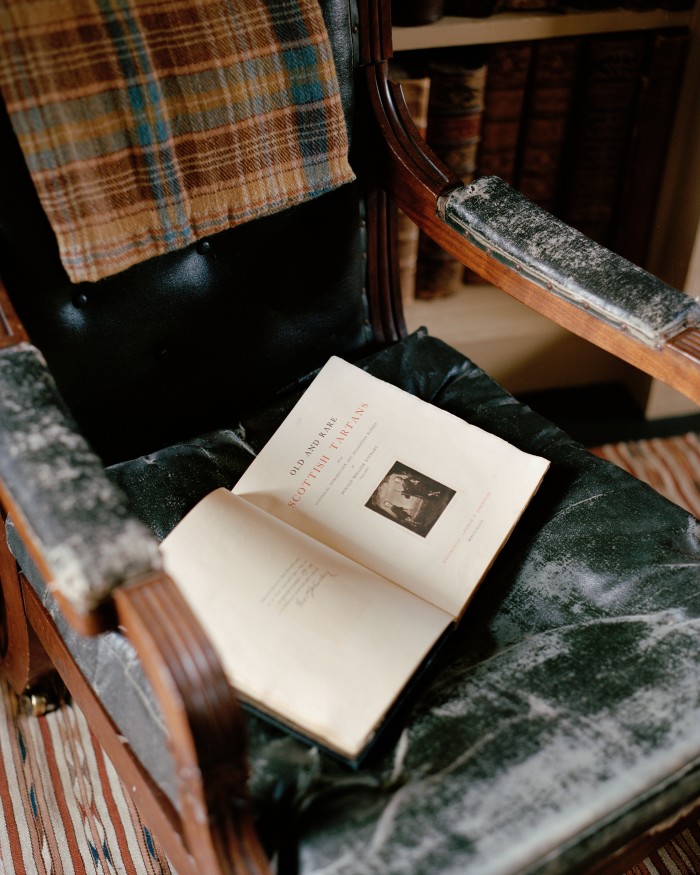

But it is art, in all its forms, that strikes you from the moment you enter the castle. Tarka’s thoughtful, intricate cut-out works hang on the walls; piles of books sit on every surface; a piano, conga drums and guitars live in the long gallery; and a composition covered in scribbles lies on a music stand near David’s desk. It makes for a curious juxtaposition with the relics of Scottish clan history that are hewn into Airlie’s walls: the vast coat of arms carved into the wall above the fireplace in the main hall, for example, or the wonderfully thread-worn carpet in Ogilvy tartan that runs up the curved stone stairs.

Stately homes and grand houses are a far cry from Tarka’s childhood home that she shared with her writer mother in a ’60s house in Chiswick, a breath away from the Thames. To make ends meet, her mother worked in the legendary Turret Bookshop, which was a magnet for the 1960s literary set, attracting everyone from the Liverpool poets to Allen Ginsberg. “Our lodger was Ralph Steadman,” remembers Tarka. “I remember him knee-deep in drawings in his room while he worked on the illustrations for Hunter S Thompson’s novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.” Hers was a unique kind of literary bohemia. “Our house was all about wooden floors and an Aga in the kitchen, and I would wake every morning to the sound of my mother tapping away at a typewriter. There were books everywhere. She lined the entrance hall in silver foil, and later in brown paper, and if we wanted to change the colour of a wall we would just paint it. My mother was not always happy and it was something nice we did together…”

Kings has brought a lot of this same easy attitude to Airlie, using lighter, more modern furniture to offset the formality. Starting by knocking down the walls of the bathroom in the master bedroom, she repositioned the bath on a raised base – “so we could look out of the window while lying in it”. She used Mallorquin blue-and‑white fabric on the window seats and bedhead, and pale-blue Portuguese tiles around the bath and sinks, which give the room an elegant simplicity. Her mother’s worn American quilt of pale pink and blue checks lies across the bed. This lightness continues to run throughout the house. “We got rid of all the dark mahogany and fussy chintz.”

Today Airlie is a relaxed and inviting space, full of pelargoniums in terracotta pots. A large scrubbed oak table designed by Arts and Crafts architect Philip Webb is surrounded by a set of ladder-back rush-seated chairs by Ernest Gimson. It dominates the main hall, which doubles as a dining room. “We don’t put a cloth on it very often, because we like the simplicity.” In a small sitting room, painted in an eco-friendly soft green-earth distemper, hangs a painting by British portraitist Gerald Kelly of a serene woman wrapped in a dark shawl, which once belonged to Tarka’s parents. On the pale floor beneath the painting lies a colourful striped rug that Tarka picked up in Ikea.

As the heir to Airlie and the keeper of the Ogilvy title, David’s relationship with his ancestral home has not always been so easy. “Music was an escape from the predictable, prescribed world I was raised in,” he says of his decision in the early ’70s to focus his attention predominantly on playing and composing. David began to find a balance between his two worlds in 1987, when he met Tarka at a country-music club called Congress that she had started and which took place every few months in different venues around London. Tarka designed its artwork, David was one of the performers. Tarka says: “We had an immediate connection – music had helped both of us to create a world that seemed more authentic to us in many ways than the ones we really came from.”

They married in 1991 and started a family. Gradually, they began to spend more time in Airlie, which had previously been inhabited by David’s late grandmother. “It was hard in the early days to be in a house that was so defined by both the history and the decor imposed on it by past generations,” says Tarka. But the couple have since brought a warmth to the house that had hitherto been lacking. The concept of Laird – and all its inherited privileges – are not much in evidence in Airlie. A typical day starts with a family pre-breakfast swim in one of the many water holes in the river. Mornings are spent in the kitchen: Tarka reading in a window seat while David and their three sons – Huxley, 28, a photographer’s assistant, Mike, 23, a drummer, and Joe, 25, a chef (David also has a daughter, Augusta, by his first marriage) – make soup at the Aga. Cooking and eating is an important part of this family’s life. From the kitchen, a low door leads into a long gallery, originally the servants’ quarters. Early on, Tarka and David converted it into a playroom for their young children. Over time it has morphed into a music room housing a pair of huge beaten-up B&B Italia sofas covered in linen with red-patterned cushions that act as a divide between the instruments and a ping-pong table. On the walls are Tarka’s collection of Wyoming number plates from her father’s car collection, which she brought back when she visited him in America.

Tarka’s father, a publisher, left the family when she was three years old and went to live with his new wife in Wyoming, where he refurbished a ranch and historic coaching inn. Tarka didn’t see him again until she was seven, and then only for one week each year. “His absence made me romanticise him,” she says by way of explaining her love of Americana – the quilts, the signage, her cowboy boots and the country music that reverberates around the house. “I went to Wyoming when I was 12 to stay with him and everything seemed so exciting. I loved the leather, the cowboy saddles, the trucks, the neon signage and the light-blasted, vast, empty spaces where colours looked so faded. I was also obsessed with Country and American singers: Bob Dylan, Townes Van Zandt, Jimmie Dale Gilmore. All these elements seemed to represent and make a character of my father.” It poured into her work while she was a student at the Royal Academy, and long after. “Even the pale blues and pinks of the airmail letters he would send me seem to have seeped into my paintings.”

The same references still feature in Tarka’s work, which she shows in London’s Offer Waterman gallery. Shadowy portraits, often of somewhat pensive-looking girls, a body of work composed of thousands upon thousands of tiny coloured pencil strokes reminiscent of Seurat, Ruscha and Agnes Martin. The paper cut-outs and more recent patchwork pieces she made in lockdown are a nod to the work of Anni Albers, as well as the faded patchwork quilt that once lay on her mother’s bed and now decorates her own. Her latest project, an installation of her cut paperwork that features detailed scaled models of existing rooms and eight pieces of jewellery, is scheduled to go on show at Chatsworth in March 2021.

David and Tarka have successfully managed to merge their working lives to harmonise with their Scottish identity. At the far end of the long gallery, an adjoining cottage built in the 18th century acts as an office for David, and alongside that is a work space for Tarka where she creates her art on a large refectory table. David works at a glass ’60s table found at Alfies Antique Market. Beside him, a black iron fireplace with a mantle is covered in family mementoes old and new, photographs and music memorabilia. “History is so strong – it’s a juggernaut. You can’t turn it so you have to make a deal with it. I had to merge my identity with this place,” says David of his relationship with Airlie. Alongside running the estate, which places a big emphasis on farming, forestry and the ecological environment, the couple are renovating the estate cottages and farmhouses to make them available for renting, and he also runs The Live Salon, an occasional gathering of musicians (including their son Mike) who play everything from classical, jazz and Latin, combined with the spoken word.

It transpires that a love of music is also in David’s DNA. A few years ago he was introduced by his American-born mother, Ginny, the Countess of Airlie, to Norbert Meyn, a historian who was then working on a project about the legacy of migrant musicians from Nazi Europe. David discovered he had a whole family on his mother’s side that he knew nothing about – Jewish cousins, all musicians, who had not left Europe during the war but had suffered and remained in Germany in hiding. In tracing this story, David found an identity he could finally relate to. “It has been an extraordinary and liberating journey for me. I went to Germany, I found a family, they looked like me and were part of me, and we all played music together, our common language. Now I listen to generations of music and I compose in response to it.”

The light is extraordinary in the garden at the end of a long day at Airlie. The anemones, buddleia, echinacea and climbing roses that border the terrace are almost technicolour in the rays of the late summer light. The clouds are lined in pink and the pale stone of the medieval wall that still seems to be protecting this house is glowing. The doors are open and the notes of a piano can be heard out over the wide lawn, into the countryside. Inside this ancient place, David Ogilvy is playing his history.

Comments