Start-ups test ideas to suck CO2 from atmosphere

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

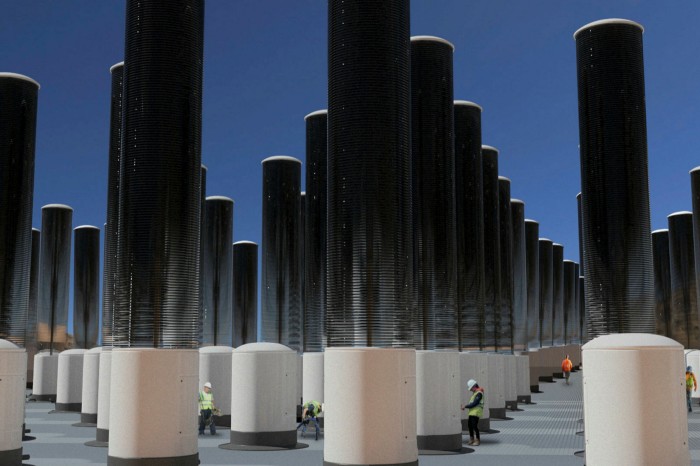

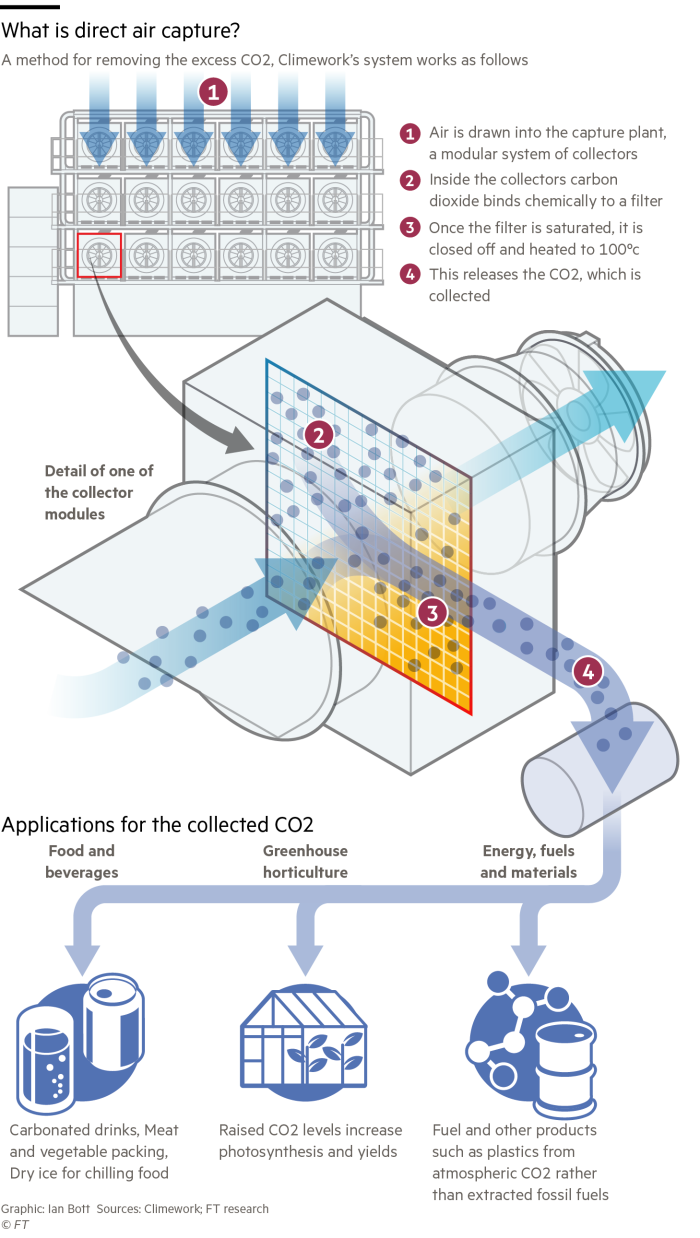

It sounds at first like science fiction: giant machines that suck carbon dioxide directly out of the air to help alleviate climate change.

The concept, called “direct air capture”, may sound far-fetched, but dozens of these machines are already operating on several continents and more are on the way.

A number of new projects and investments in the past six months have helped to bolster the nascent sector, which is comprised of a handful of small start-ups vying to perfect the technology.

There are still significant drawbacks: direct air capture is currently very expensive, although researchers expect it to get cheaper. Extracting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in this way costs more than $200 per tonne, while other methods such as tree planting can cost as little as $10 per tonne.

Nevertheless, investors and energy companies are ploughing growing sums into direct air capture ventures. In June, Switzerland-based Climeworks closed a $75m funding round, which it will use to build more carbon dioxide collectors.

Meanwhile, Canada-based Carbon Engineering has been working with Occidental Petroleum, the Houston-based energy group, to design and build the world’s biggest direct air capture plant. It will be capable of pulling a million tonnes of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere every year — the equivalent of 40m trees. Construction is expected to start next year.

Newer start-ups are also entering the fray. Ireland-based Silicon Kingdom, which currently has just 30 employees, says it will build and install its first direct air capture machine by November.

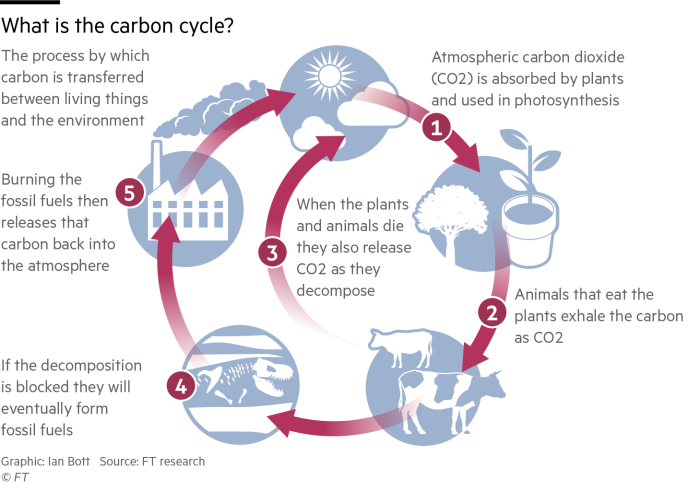

All of these companies share the same goal: to pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to compensate for the emissions that humans have generated by burning fossil fuels. But their business models and technical approaches vary widely.

In Switzerland, Climeworks is selling some of the extracted CO2 gas to nearby greenhouses, where it acts as a fertiliser to help the plants grow faster.

In Texas, the plant being designed by Carbon Engineering and Occidental will produce CO2 that is injected into oil wells to help improve the extraction rates of the fuel reserves from geological reservoirs — a process known as “enhanced recovery”.

Carbon Engineering’s chief executive Steve Oldham says the company will also produce synthetic fuels — which could be used in aviation — at its new research facility in Canada. This can be manufactured by recycling the carbon molecules pulled from the air with hydrogen to synthesis combustible fuel.

“You are reversing the process of all that CO2 that we have been putting into the atmosphere for all these years,” he explains.

Silicon Kingdom says its primary market will be companies and governments that want to offset their emissions by pulling an equivalent amount of CO2 out of the air.

“A lot of the big companies have made commitments to go carbon neutral. What you see lacking from those statements, is how are they going to get there,” says Pól Ó Móráin, chief executive of Silicon Kingdom. “What we have is the enabling technology to fit alongside those commitments.”

The company has adopted an unusual “passive” design for its first machine. Instead of sucking in air using big energy consuming fans, the company describes the machine as a “mechanical tree” — the wind simply blows across it and the CO2 in the breeze is absorbed by discs soaked in chemicals.

On average, carbon dioxide represents only 0.04 per cent of the air around us. That level is creeping up as humans continue to burn fossil fuels, but even at such low concentrations extracting carbon dioxide from the air is still a challenge.

Interest in direct air capture has been boosted by the recent stream of companies, and countries, that have pledged to cut their emissions to “net zero”. Such commitments involve cutting emissions to as low as possible, then compensating for any remaining emissions with programmes like tree planting or direct air capture.

As well as seeking cheaper ways of capturing carbon dioxide, proponents are also searching for the best way of storing it — often in disused oil and gasfields or other suitable geological reservoirs — to prevent its leakage back into the atmosphere.

“As countries have adopted increasingly ambitious targets, they realise they need a lot of carbon dioxide removal,” says Julio Friedmann, a researcher at Columbia University and an adviser on carbon removal projects. He is optimistic about what that means for direct air capture, particularly as the technology matures and the cost comes down.

“It is helpful to think about direct air capture as being like where solar was in 2005,” he explains. “It was expensive, people were buying small units . . . But in 10 years that story really changed.”

Comments