Chip crisis highlights supply chain new order as carmakers lose out

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

With sprawling global production networks and immense buying power, carmakers are used to being at the top of the food chain when it comes to negotiating with suppliers.

But the digitisation of cars has plunged them into the new and unfamiliar arena of microchips, where their negotiating power is significantly lower.

In markets such as steel and aluminium, the carmakers have the size and muscle to get what they want in a big contrast to chips, where they are minnows up against the Silicon Valley laptop and smartphone giants.

This has caused the latest industry crisis for the car groups, which rely on chips to power everything from braking systems, power steering, wipers to windows, as they have been forced to wait in line behind the California technology groups before they get their orders.

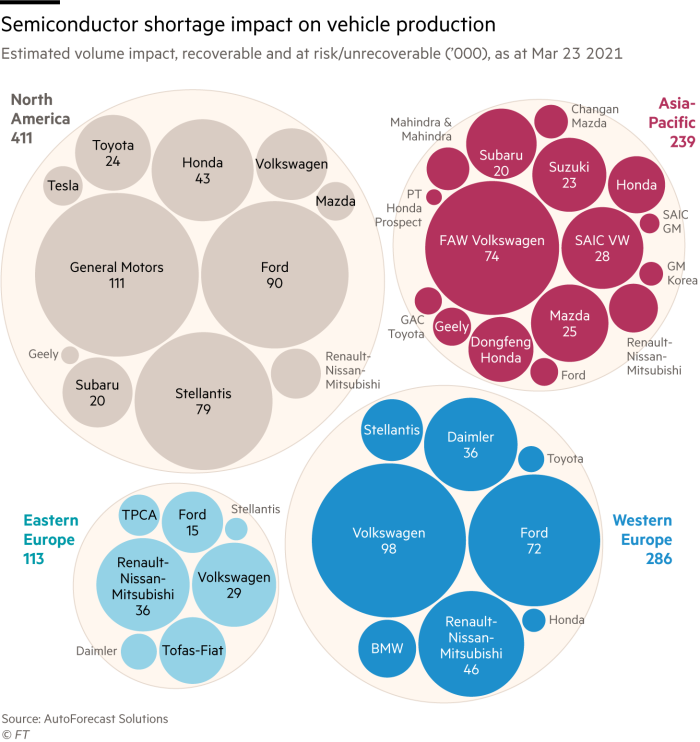

The result has been a chronic shortage that will cost the carmakers billions, with the world’s biggest groups including Volkswagen, Toyota and General Motors halting production and suspending manufacturing forecasts because of the chip drought.

For an industry reliant on finely-tuned supply lines, where groups typically hold only a day or two worth of parts for just-in-time manufacturing to maximise efficiency, it is a stark reminder of the fragility of the network that underpins their entire model.

“We are facing an unprecedented crisis with Covid-19,” said Ashwani Gupta, Nissan’s chief operating officer. “One of the things it has highlighted is the vulnerability of our supply chain.”

While several factors are at play, including the huge rise in demand for computers for homeworking, the shortage, which began last year, stems from the sector’s second-tier status behind the technology groups.

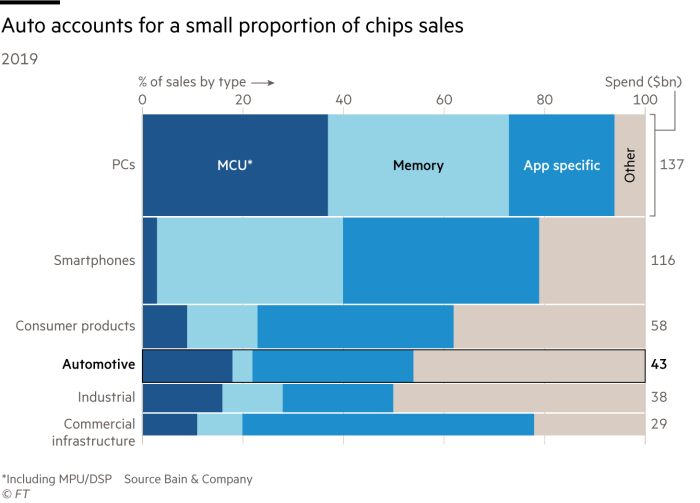

Figures from Bain & Company estimate carmakers account for just 10 per cent of the world’s chip buying against those of smartphone and laptop makers, which make up about three-fifths of the global market.

“Other sectors are ready to pay premiums to secure supply,” wrote analysts at Bain, in contrast to auto procurement executives who are used to fighting for every cent of saving.

“The semiconductor shortage is one of the issues that is catching us by surprise,” admitted Nissan’s Gupta. “We may expect more such surprises, mainly due to the ripple effect of the pandemic.”

Unfortunately for the sector, there have been a number of nasty surprises.

The Texas freeze was one of them with the widespread shutdown of oil refineries, critical for manufacturing the plastics that are used for everything from foam for car seats to airbags.

This was followed by the grounding of the giant container ship Ever Given in the Suez Canal, hitting supplies of car parts from Asia to Europe that cannot pass through the waterway.

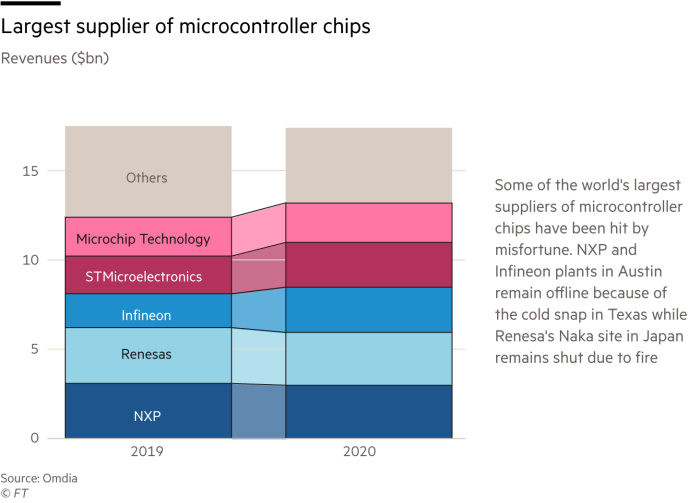

In another setback, a fire in the clean room at Japan’s Renesas, the world’s second-largest supplier of microcontroller chips for cars after NXP, added more strains.

The company warned it would take at least a month to resume production, with analysts saying a full recovery will take three months or longer.

According to Jochen Hanebeck, Infineon’s chief operating officer, it would take until June to return to pre-shutdown production levels, while NXP has warned of a $100m revenue hit from the disruption.

“It’s unheard of for such incidents to happen all at the same time. The impact will be considerable,” said Akira Minamikawa, analyst at research firm Omdia.

But, even once the supply chain starts to flow again, carmakers will face the same problems in the plastic and chip markets — being last in the line.

As a result, they are considering how to change their models to avoid future squeezes as the need for semiconductors becomes all-important with the advent of computer systems that control everything from safety, infotainment to driver-assistance systems in vehicles.

Volkswagen, which expects a reduction of at least 100,000 cars in the first quarter because of chip disruption, is looking at overhauling the way it manages the sourcing of parts.

“It is too early to come up with concrete measures yet, but rest assured we are looking into this topic,” the company’s incoming chief financial officer Arno Antlitz told the Financial Times.

But, until then, the industry has to find a way to plug the gaps, which may be easier said than done as alternate suppliers need to be certified, which can take months.

“Certification is a good process to make the vehicle safe, but when you end up with disruption, it’s really difficult to replace it,” said Daron Gifford, who runs the automotive division at consultancy Plante Moran.

The latest setbacks, he said, show how high-risk the reliance on just-in-time deliveries are, where anything from a snowstorm in the US to a fire in Japan can throw the whole mechanism off balance.

“If you make a vehicle with 9,000 parts, and if one doesn’t work or isn’t there, then it’s a defective vehicle,” he said. “The supply chain is very lean.”

Comments